With multiple iconic television roles under his belt, LeVar Burton has secured his place in TV history. He burst onto the acting scene in the role of Kunta Kinte for ABC's seminal 1977 television miniseries Roots, which earned him a nomination for Outstanding Lead Actor for a Single Appearance in a Drama or Comedy Series. A decade after that, he took on the role of Geordi La Forge in Star Trek: The Next Generation, which carried over into feature films and the Paramount+ series Star Trek: Picard.

In between playing those two unforgettable characters, Burton was a virtual member of many childhoods as host of the long-running PBS series Reading Rainbow, bringing a love of reading to millions of children. His literary advocacy continues today with his LeVar Burton Reads podcast.

In addition to many other acting roles, Burton has directed a number of episodes of Star Trek and other series. He was a popular guest host on Jeopardy! and has a park named for him in his hometown of Sacramento. Burton was nominated for three primetime Emmys and won 11 daytime Emmys as host and executive producer of Reading Rainbow. He was recognized by NATAS, the governing body of the daytime Emmys, with the first Children’s & Family Emmy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2022. His many honors also include a Peabody Award in 1992 and a Grammy for Best Spoken Word Album in 2000.

Burton was interviewed in January 2009 by Steven Wishnoff for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

What did you want to be when you grew up?

I wanted to be Sidney Poitier. When I saw Lilies of the Field for the first time in 1963, at the drive-in, laying on the roof of our station wagon, that was eye-opening to me. Here was this Black man on the big screen who was as smooth and as elegant and as articulate as anyone. That’s what I wanted to be.

When you were 13, you entered the seminary ...

My journey to the seminary was really prompted by my mother. I was educated in the Catholic tradition, because my mother was a teacher, and when we moved to California, even though she herself was not a Catholic, she knew that the best education available for my two sisters and myself was a parochial school education.

At that point my parents’ relationship was imploding. And, subsequently, priests became the most constant male role models in my life. My mother’s second career was as a social worker — she was an English teacher first, and then a social worker. So, I grew up in a family where one was expected to put one’s life in the service of others.

My mom always used to talk about the fact that I would grow up and inherit a world that would oftentimes be hostile to my presence. She firmly believed that the best tool I could have to level the playing field in life was an education. I was incubated in an environment where I was really drawn to the priesthood.

What interested you during your high school years?

Well, seminary was high school for me. I was at St. Pius for four years, from ages 13 to 17. It was there that I decided not to become a priest. I had a great teacher my second year at St. Pius. He was an English teacher, my favorite subject. He was also the drama coach. He taught philosophy as well. Lee Bartlett was the person more responsible than any other at that time to really open me up to what was out there in the world. And the things that we were reading with Lee — existential philosophy and Eastern philosophy — just pointed a direction to me that led outside of the confines, as I experienced them at that time, of the Catholic dogma. That was coupled with the end of the Vietnam War and just really wanting to experience the world. I figured there was a better way than wearing a collar. So, I decided not to become a priest. And in taking stock of that which I felt I had as assets, I settled on becoming an actor.

You studied theater at USC?

I was a bachelor of fine arts major in drama. We took drama, acting, dance, dramatic analysis and theater tech, which was crew and stagecraft. It was glorious, because we ate and slept and dreamt theater. It was heaven for me.

What led to your first TV job?

I’m at USC auditioning for every play I possibly could, not thinking about film or television at all. And they were casting for what they were calling a “miniseries.” Nobody knew what a miniseries was. They had exhausted all of the normal means of finding professional talent. They had seen every young Black kid who had an agent in Los Angeles, Chicago and New York. So, they cast the net wider. They started calling drama schools around town. One day there was an announcement made in one of my classes that they were looking for some young Black kids for a miniseries based on a book by Alex Haley. My freshman year at USC, I’d done a term paper on Malcolm X, and Alex Haley cowrote, along with Malcolm, The Autobiography of Malcolm X. So, oddly enough, I knew who this man was. I firmly believe that everything happens for a reason.

Had you read Alex Haley's Roots: The Saga of an American Family?

The book wasn’t released yet. The only thing I had been able to read were the sides. And when I read the very first sides, I knew this was something that I could do. I just felt I knew this kid [Kunta Kinte]. I knew how he felt. I believe in that idea of genetic memory. When we shot the Middle Passage, production had rented a warehouse outside of Savannah and built the interior hold of the ship, and we went in there for three days. Alex came to me a couple nights before and brought me a galley copy that had a bookmark where the Middle Passage began, and he said, “I want to give this to you, because it might be valuable for what we’re about to start shooting.” Alex was there all the time, which was amazing.

I remember reading at night, going to work during the day, and just becoming immersed in the feeling of the Middle Passage. But when we started shooting it, I remember pretty much the first day. I have flashes of moments of those three days. I’m convinced I checked out and there was another spirit — a presence — that came in to help me survive. Because at that point I was so into the experience of Kunta. I was living that life, in an emotional sense. And those are three tough days. A lot of the extras that we brought in couldn’t hang in the recreation. The prop guys made this goop of oatmeal and stuff to represent the vomit. Lying on the planks, the heat and the feeling of the oppressive atmosphere … it was intense. But I know there was something — someone — that was helping me, protecting me, enabling me to go through that experience.

It's well-documented that director David Greene wanted Kunta to be accessible and identifiable as a person. Is there anything you specifically did to fulfill that?

I had a really intense desire to just be as true to what I was reading as possible. It wasn’t just me. I was the new kid on the block. My very first day as a professional actor, Cicely Tyson played my mother. Maya Angelou played my grandmother. The cast that came through Savannah at that time — Moses Gunn, Hari Rhodes, Ji-Tu Cumbuka, Louis Gossett Jr. — these people were my idols, and they took me under their wing. These really revered elders were all talking about how never before in their careers had they had an opportunity to express the Black experience from this point of view.

Alex used to say all the time that history is oftentimes written by the winners. The story of slavery in America had never been told from the Africans’ point of view before. When I was in school and we studied slavery, it was always discussed in terms of the economic impact. Roots put a human face on that part of our shared, Black and white American, common history. Roots played in some 50-odd countries around the world, always to the same result. It was always universally embraced, because the story of Alex Haley’s family is a universal story. The theme of the indomitability of the human spirit is expressed in Kunta Kinte; the theme of the survival of the human being is expressed through the character of Fiddler; the importance of continuity; the importance of maintaining one’s identity through generations. These are ideas that everybody can relate to, so this was huge. And I think everybody had a genuine commitment to do the material justice, and to do the folks back home proud.

What effect do you think Roots has had on the global public?

I see a direct thread of continuity that runs from the post-Reconstruction South through the Civil Rights Movement, right through Roots to Barack Obama. We wouldn’t have Barack Obama, certainly, without the Civil Rights Movement, and certainly without Roots in the ’70s. Because, in its way, Roots helped expand the consciousness of this country, of this culture. And in the same way that Barack Obama, by virtue of his presence, expands everyone’s idea around the world of what it means to be a Black man, Roots helped expand everybody’s idea of what it means to be a part of this America and how slavery shaped the America that we have today. I genuinely believe that race is, in this country and this culture, one of the few things you can trace back to the heart of everything that happens here. And unless we can come to terms with the legacy of slavery, it’s impossible for us to live fully in the present, and it makes no sense to try and forge a future. So, I think Roots was hugely instrumental on a psychological level, on an emotional level, for people on both sides of the color line in America. And I like to think it helped pave the way for Barack Obama to be elected.

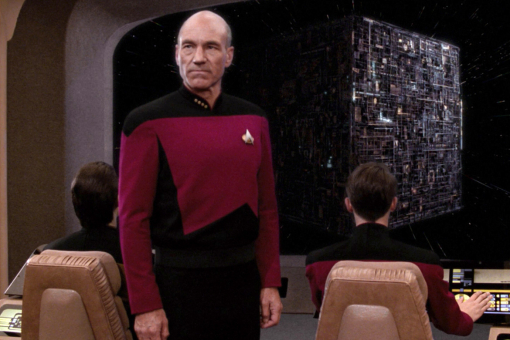

How were you cast on Star Trek: The Next Generation?

Well again, everything happens for a reason. In the early ’80s, I did a TV movie called Emergency Room. The producer of that show was a man named Bob Justman. I was a fan of the original Star Trek series, and I knew that Bob Justman was Robert H. Justman, the associate producer of the original Star Trek series.

Star Trek was really important to me when I was growing up, so I would pump Bob for Star Trek stories. He knew of my passion for Star Trek and my love of the universe that Gene Roddenberry created, so when they were working on The Next Generation at Paramount, I got a call from Bob. I’d never done a television series before. And they weren’t looking for names. They wanted to create a cast of unknowns. But Bob called and said, “Would you be interested?” I only asked one question: “Is Gene involved?” He said, “He absolutely is.” I said, “Count me in.”

I went and read for the part. I had to win the role. But again, I read the sides and I thought, “I got this guy. I know who this man is.” Playing Geordi [La Forge] was in its own way not unlike playing Kunta. Having Nichelle Nichols on the bridge of the Enterprise said so much to Black people. I’ve had this conversation with Whoopi [Goldberg] — that’s why Whoopi joined the cast of The Next Generation, because she was such a fan of the original series. Mae Carol Jemison, the first African-American woman to fly on the space shuttle, same story — seeing Nichelle on the bridge of the Enterprise meant the world to us and to so many others.

So, for a person dealing with a physical challenge, as Geordi does [La Forge was born blind and uses a VISOR — a Visual Instrument and Sensory Organ Replacement — to see], I get what seeing that character on television felt like. And people come up to me all the time and say, “I’m an engineer today because of your work on Star Trek.” People in wheelchairs, people dealing with physical challenges, they come up to me and tell me how important it was to see themselves represented on that spaceship. I understand, because I was one of those people who needed validation in the popular culture when I was growing up. And that’s the power of the medium. That’s one of the things we’re able to do by telling these stories — giving ourselves an idea that we’re all in this together. That’s what Star Trek represents to people: When the future comes, there’s a place for you.

How did you become involved with Reading Rainbow?

I had done a couple seasons of a PBS children’s series that was produced out of WGBH in Boston called Rebop. I had always been a fan of PBS and really admired their approach to the public airwaves and their mission.

I was on my way to Africa and was in New York City doing Live at Five with Sue Simmons. They were looking for a host of Reading Rainbow and saw me on an interview and tracked me down at the Carlyle Hotel. Again, everything happens for a reason. In my mother’s house you either read a book or got hit in the head with one. I grew up in a family where my mother didn’t just read to us when we were kids, she read in front of us. I grew up knowing that this was what we did: You read. I’m acutely aware of how literature has shaped my life. Combine that with the Roots experience where I, from first-hand experience, saw just how powerful this medium is, and the idea of using television to steer children back in the direction of literature and the written word just made so much sense to me. They asked me if I was interested, and I was like, “Absolutely. Let’s do it.”

We always saw books as a jumping off point from which we could go experience the world. I think that was the magic of Reading Rainbow — that we really did portray books as a portal to life experience.

What advice do you give an aspiring entertainment professional?

Find something else to do. I mean that. Because it’s not for the weak of heart or the weak of spirit. Had I known then what I know now, would I still have embarked on this journey? You bet. I absolutely would have. But my feeling is, if I can convince you to go and do something else, then this really wasn’t for you in the first place. It’s way too hard. There’s way too much rejection. These days kids get into this business and they want to be television stars. They don’t want to be actors. They don’t have a real connection to that craft, to the first actors on this planet that came from the spiritual tradition. Acting has evolved from that part of us that took care of the spiritual needs of the community. It’s a noble and ancient profession, in my view. If you want to do it right, you want to do it for the right reason, which is you have an absolute burning desire to connect with people. That’s different than just wanting to be famous.

The contributing editor for Foundation Interviews is Adrienne Faillace.

Since 1997, the Television Academy Foundation has conducted over 900 one-of-a-kind, long-form interviews with industry pioneers and change-makers across multiple professions. The Foundation invites you to make a gift to the Interviews Preservation Fund to help preserve this invaluable resource for generations to come. To learn more, please contact Amani Roland, chief advancement officer, at roland@televisionacademy.com or (818)754-2829.

Click here to see more interviews.

The full version of this article originally appeared in emmy magazine, issue #8, 2024, under the title "Foundation Interview: LeVar Burton."