Michael Douglas didn't get his start on The Streets of San Francisco, but the series gave him his first major role and marked a turning point in his career.

The son of acting-producing giant Kirk Douglas, he made his screen debut in 1965 in his father's film Cast a Giant Shadow. His early TV appearances were on shows like The FBI and Medical Center and the aptly named ABC telefilm When Michael Calls. Then came Streets, for which he would receive three Emmy nominations. Over its five-year run — from September 16, 1972, to June 9, 1977 — the show notched sixteen Emmy noms.

Edward Hume (Cannon, Toma) created the show, adapting it from Carolyn Weston's 1971 thriller Poor, Poor Ophelia. Quinn Martin — who had at least one series running in primetime every season from 1959 to 1980 — was executive producer.

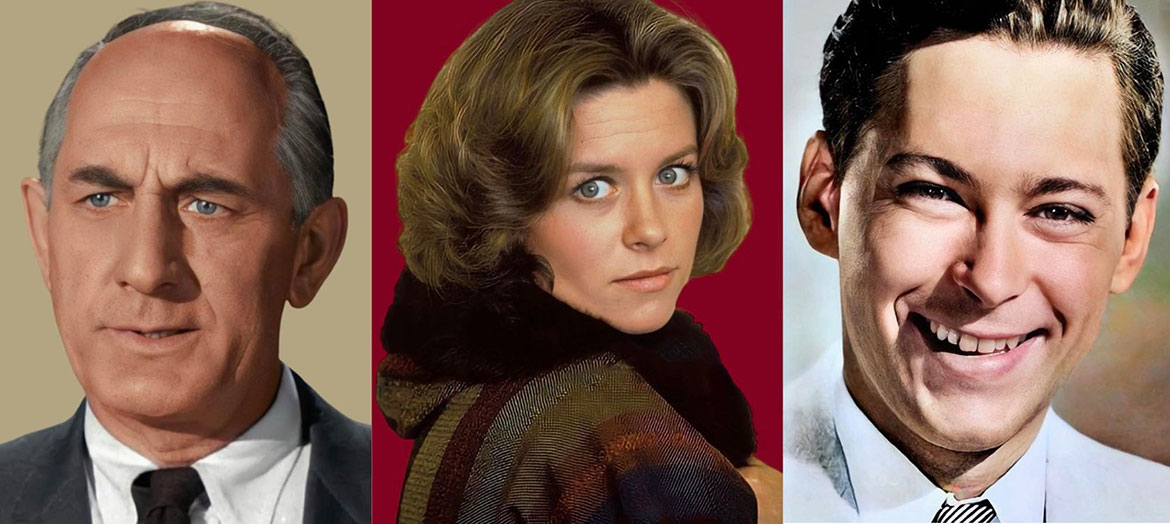

In a classic cop pairing, veteran actor Karl Malden brought rubber-faced charm to old-school Detective Lieutenant Mike Stone, while Douglas's teen-idol looks helped newly minted Inspector Steve Keller appeal to younger viewers. Malden's perennial fedora and sweater vests evoked an earlier time, and Douglas's longish hair and contemporary sport jackets embodied a new era.

Malden, who died in 2009, was nominated for four Emmy Awards for Streets but finally won one for his chilling performance as Freddy Kassab in 1985's Fatal Vision. Earlier, he had won an Oscar for the 1951 classic A Streetcar Named Desire and was nominated again for 1954's On the Waterfront.

In their four seasons together, Malden and Douglas brought to life an unstoppable crime-fighting team. The show's solid cast of semi-regulars also delivered; it included Darlene Carr, Robert F. Simon, John Kerr, Reuben Collins, Lee Harris, Ray. K. Goman, Vince Howard, Fred Sadoff and Stephen Bradley.

In the final season, after Douglas left to produce One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Richard Hatch (later known for Battlestar Galactica) joined as Inspector Dan Robbins, Stone's new partner.

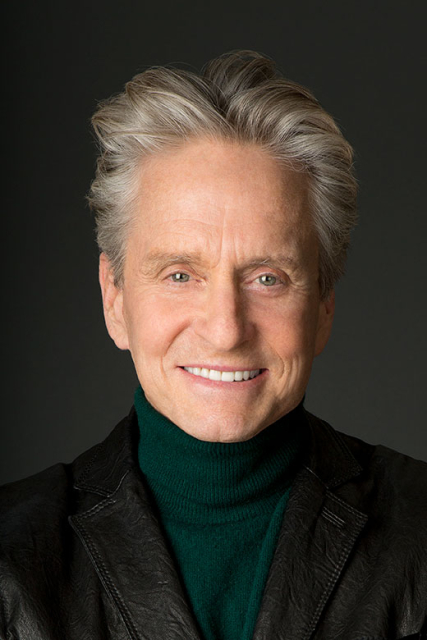

Douglas, of course, went on to produce and star in dozens of movies, including 1987's Wall Street, for which he won his second Oscar, and its 2010 sequel, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. In 2013, he won an Emmy, a Golden Globe and a SAG Award for his portrayal of Liberace in HBO's Behind the Candelabra. More recently, he has played Dr. Hank Pym in three Marvel movies and received four Emmy nominations for The Kominsky Method, which he toplined on Netflix for three seasons.

Douglas shared with emmy contributor Herbie J. Pilato his memories of The Streets of San Francisco and Malden, whom he credits with ensuring the show's enduring integrity.

What made the scripts so superior on The Streets of San Francisco?

For me, the show was my first big opportunity. For Karl, it was the twilight of his career. He was renowned for his work ethic, and he set the tone for the show in more than a few ways. For one, he had it written in his contract that, while working on one episode, he would have the next week's script in hand.

Whenever there was a break in shooting, Karl would take me aside and we would run lines for the next week's script. By having the scripts completed earlier, we had a chance to review them, and rewrite them [if necessary]. The writers were a little frustrated because our scripts ran about eight pages longer than most of the other Quinn Martin scripts, simply because we were so well-rehearsed.

How did the show differ from other Quinn Martin productions and from 1970s police dramas in general?

Our show was shot in San Francisco, and that separated it from other shows at the time. The first year, we went back and forth between studio work and some location filming. But then we realized that it made sense to shoot the entire show in San Francisco. At that time, in television, there wasn't much location shooting going on. And filming a show that was based in San Francisco created a wonderful environment.

But in the first year, we were not warmly received by the San Francisco media, who felt we were exploiting their city. Karl and I were kind of hurt and a little offended. But by the second year, the show had become such a hit, all of San Francisco realized that it was a love letter to their city. It was an homage — the greatest one-hour commercial the city could possibly have. So their tune changed very quickly. We were made to feel like part of the town and its people.

How did you become involved with the series?

I had appeared in a CBS Playhouse [episode] called "The Experiment" with Tisha Sterling, which was written by Ellen M. Violett. It was reviewed well, and I moved out to California and was contracted with CBS Films. I made a couple of movies with them and then began to do episodic television, including The FBI, which was produced by Quinn Martin.

Quinn was a successful producer with many shows on the air, and he was entangled in a lawsuit with ABC, which had made a commitment for a series that they reneged on. Quinn sued ABC and won. As a result, he got an hour show with twenty-six episodes, plus a two-hour film that introduced the series.

Very seldom is there a commitment like that. A network usually gives you a pilot and maybe a short order of six episodes. But this was a guaranteed twenty-six episodes plus a two-hour movie. My agent said, "Listen, for you as a young actor, this is a great opportunity. Quinn Martin is an excellent producer."

Quinn definitely had a classy patina. And Karl Malden was an Academy Award winner. He had worked closely with those like Marlon Brando, and when I worked with him, I began to learn why so many people wanted to work with him — because he was so good.

As a young actor, I still had a little bit of stage fright in front of cameras, but I could not turn away from such an incredible opportunity with a commitment for an entire season.

How was your chemistry with Karl?

Chemistry is a unique thing. I had it with Annette Bening when we did The American President [1995], and it was there with Karl when we did The Streets of San Francisco, because he made himself accessible.

He was the lead and back in those days, when filming, the second lead was usually about two feet back from the lead, filmed in soft focus. The focus couldn't hold both. But Karl looked at me and said, "Hey, Buddy, come up here. You take the front."

Very early on, he realized that just because he was number one on the call sheet, that didn't mean he always had to be in the number-one position on camera. He knew how important it was to sometimes stay in the background. He was very comfortable allowing me to take the front spot once in a while. And I am indebted to him for that courtesy.

So much of the show involved you and Karl driving in the famed Ford sedan, with the portable siren. Any memories of those journeys?

I remember all the long exposition scenes that we would do while I was driving the car. There was a sound man in the trunk, and we would do a five-page scene and the director would stay in the back.

In those days, we had those old Panavision cameras with a thousand reels. And we had them stacked on either side of the car, going out and doing cross-shots on me and cross-shots on Karl and the other way around. I would turn on the camera and then start driving. One police officer would be in driving in front of us, another would be in the back and another would be stopping traffic at the stoplights. It was insane. We'd drive with these big cameras hanging off the sides of the car. I didn't know if we'd have enough room to fit through [the lanes]. We had no plan. No map.

But my most vivid memory is from the first day we filmed. We were on top of Nob Hill and it was getting late. The AP banged on my dressing-room door and said, "We gotta go! We're losing the light! This is just a drive-by, so we need you right away."

I rushed out to the car, and Karl was seated inside. The AP said, "Okay, once you go down the block, go around Nob Hill, past the Fairmont Hotel and down that hill." And he said, "Karl, you put the gumball [light] on the roof!"

I prided myself on being a pretty good driver, driving Formula One racing cars and such. So I didn't bother to mark out the route. They said, "Go here, down that corner and around."

The director yelled, "Action!" Karl put the gumball on the roof, and I drove down to the Fairmont and up the hill. And all I can tell you is that I went off the hill, totally airborne.

While in the air, I had time to look over at Karl, and he looked back. The car wheels were squealing when I stopped the car. Karl got out and said, "You call that driving? That's not driving! That's theatrical driving!" I thought, "Oh, my God! I'm gonna get fired the very first day I'm here."

At which point, Karl said, "Okay, I'm done. I'm going back to my trailer and change my underwear."

Did you leave the show because you wanted to stop acting or because you wanted to start producing?

I always wanted to act. I never even thought about producing. It was simply my love for [Ken Kesey's 1962 novel] One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest — and that I was able to have access to the material because my father had the property at one time.

In my third year with The Streets of San Francisco, I was feeling comfortable and there was no question I wanted to take advantage of the opportunity of being allowed to direct an episode. It all had to do with how much more comfortable I was becoming with the entire process of filmmaking. And for all the separation back then between television and feature films, I still considered the show a fifty-two-minute film that was shot in seven days. And you learn a lot.

So was being on the show like an education?

Once we got to San Francisco, we shot six days a week. And an hourlong show at that time involved seven shooting days, which meant one week and one day for each of twenty-six episodes. So, that's about six, seven months of the year... straight, you know?.

So, I learned a lot. I learned about script structure, because we had the prologue, four acts and the epilogue — that format was Quinn Martin's line. I learned about discipline and work ethic and having to maintain that kind of schedule. Working with different directors. A different guest star each week. This was phenomenal training. It was like an entire career in one season.

But you left in the fourth year to produce One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

Yes — and it made me the worst boss in the world. I'd tell [the actors and production team on the film], "All right, here's how it worked [on The Streets of San Francisco]. I did twenty-six hours a season, plus a two-hour movie. Six days a week. We would work for sometimes eight-and-a-half months straight."

So, nobody worked harder than we did. I think that work ethic stayed with me for the rest of my life. Plus, I kept my eyes open, and I learned a lot about production. People were sort of shocked how much I knew when it came time for Cuckoo's Nest. So, I was very grateful. And both Quinn Martin and Karl knew of my passion for Cuckoo's Nest. When I was finally able to get it financed and prepared, I went to them and asked them to let me out of the contract for the final, fifth season.

Streets was a big hit show. Everybody thought I was nuts. They asked, "You're going to leave a big hit show?" And I said, "I really want to do this."

Today, in television, nobody is going to let you out of your contract. But both Quinn and Karl said, "Absolutely. Go for it. We loved working with you." I always look back and think about how fortunate I was at that early point in my career to be associated with two mensches like Quinn and Karl.

What was Karl like to work with?

We loved each other. He always told me, "You're the son that I never had. I had my daughters but didn't have a son." And, as influential as my father was, I could never really deal with him in a professional, working relationship. But I ultimately found my niche with Karl. He had such a strong work ethic, and I found that helpful. Though I did try to loosen him up a little bit. I'd crack a joke or find some humor somewhere so he could relax a little bit, and not be so tough all the time. [He smiles.]

You've become an icon. How have you managed to stay so grounded?

Thank you for that. People talk about the advantages and disadvantages of being a second-generation actor. Being around my father and watching how he conducted himself in front of people, in front of the press, or simply acting in scenes — seeing all that opened my eyes to the reality of the job. That had a big part in my professional development.

But the second big influence in my life and career was Karl Malden. He was from Gary, Indiana, a steel-mill town. He used to talk about how hard that work was, and the deep appreciation he had for acting. And what a great gig it is and how it should never be taken for granted.

Didn't your father work with Karl?

Karl Malden and my father were in summer stock together. They changed their names at the same time. Karl was Mladen Sekulovich and Dad was Issur Danielovitch. And they realized, pretty early on, those [names] would be pretty tough to fit up in lights on marquees and screens. So, Mladen Sekulovich became Karl Malden and Dad became Kirk Douglas. Dad told me about Karl and what a great guy he was. And then Karl became the mentor of my life, someone from whom I learned so much.

One of the things I learned was how much he worked to make other actors comfortable. Even though he spent most of his career in a supporting-role situation, he always made other actors feel comfortable. Because he wanted the other actors to do their best work. And when you're tense, you don't do your best.

So he was never afraid of being upstaged or somebody stealing a scene. He knew that if he was good and everybody around him was good, he'd be good. That was a very important lesson for me — that, and the amount of time we would spend [preparing for] a scene.

Sounds like the show was a transformative experience.

I was fortunate to get the show, and I will be eternally grateful for the experience. The Streets of San Francisco made way for my entire career, including as a producer. I applied the wonderful lessons that I learned on that show to all the other projects that happened after.

Herbie J. Pilato, host of Then Again, a classic TV talk show streaming on Amazon Prime, is a writer, producer, and the author of several books including Twitch Upon a Star: The Bewitched Life and Career of Elizabeth Montgomery and Mary: The Mary Tyler Moore Story.