For television audiences in 1994, there was life before and life after watching the pilot for ER.

When NBC’s landmark series premiered 30 years ago on September 19, 1994, with the two-hour pilot “24 Hours,” the network forever changed both what a prime-time medical show could do and the medium that made it. From the pilot’s opening scene — where the earnest Dr. Mark Greene (Anthony Edwards) awakens from one of his many all-too-brief naps — to supervisor Dr. David Morgenstern (William H. Macy) telling him “you set the tone,” ER would go on to set the tone for how diverse, thrilling, emotional, vulnerable and resonating an episode of television could be.

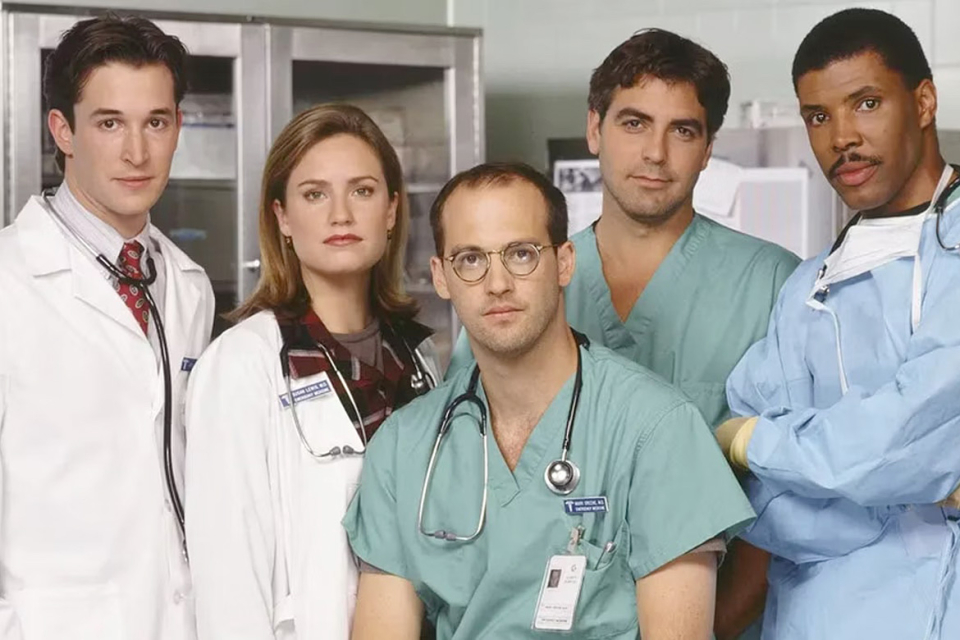

And week-to-week, during the show’s first season, watching ER was like watching competency porn. After spending an entire season of television with Doctors Greene, Peter Benton (Eriq La Salle), John Carter (Noah Wyle), Susan Lewis (Sherry Stringfield) and the most handsome pediatrician who ever lived, Doug Ross (George Clooney), most viewers arguably wanted to trade their real doctors for the ones they saw on TV. Or pay double their insurance deductibles to be lucky enough to fall under the consummate care of Nurse Carol Hathaway (Julianna Marguiles), a character who famously wasn’t meant to survive past the pilot. (More on that later.)

With a script from Harvard-trained physician turned novelist and screenwriter Michael Crichton that was retooled by showrunner John Wells — along with the creative oversight of executive producer Steven Spielberg — ER would go on to become not just one of TV’s biggest hits, but the standard by which all subsequent medical dramas would be measured. Because ER proved to be more than just capturing traumatic, life-and-death stakes through the thrilling lens of a Steadicam. ER was a show about relatable medical professionals who made the tough sacrifices every day so we didn’t have to. It was a show about how, when you face a crisis, it’s not there to expose you as weak. It’s there to show you how strong you really are.

In honor of ER’s 30th anniversary, here is the Television Academy’s oral history of how the pilot almost flatlined before it aired, as told by some of the key cast, crew and creative executives responsible for making it.

Code Blue

In 1993, NBC was in trouble.

The network was in need of a replacement for its Thursday night, 10 p.m. crown jewel, L.A. Law, which was on the way out (1994 would mark its series finale). The network was so desperate at the time, they considered giving Jay Leno then what they would ultimately give him during the 2009-10 season: A primetime show that would air every night at 10 p.m. NBC also considered, and courted, talent from one of its competitors.

Warren Littlefield (NBC entertainment president, 1991-99): Bob Wright [the former CEO of NBC] had met with Diane Sawyer. She was on the rise at CBS News at the time, and Bob seemed very hopeful that Diane would come over to NBC.

The plan would be to give Sawyer a nightly newsmagazine show, Monday through Friday, at 10 p.m. Had that plan gone through, there would be no ER. But with the success of Spielberg’s collaboration with author and filmmaker Michael Crichton on their summer blockbuster, Jurassic Park, their working relationship would soon reverse the network’s fortunes.

John Wells (showrunner and executive producer): I always tell people that, in over 30 years, these stories have been told many times — and people have different versions of them. So this is my recollection three decades later: An agent at CAA, Tony Krantz, called — I think this was in 1992 — and told me that [Spielberg’s production company] Amblin was looking to get into television.

Noah Wyle (actor, Dr. John Carter): Now we had heard that Steven — he approached Michael about possibly writing the sequel to Jurassic Park. But Michael, he didn’t want to do it. So he instead dug up his old ER script and said: “Let’s do this instead.”

Wells: They had this feature [screenplay] that Michael had written based on his medical background, and I had just done China Beach [an ABC medical drama set during Vietnam], and they brought it to me.

Littlefield: I think it’s fair to say it was a “starfucker” meeting [laughs]. It was a pitch that was late in the week, and it was in NBC’s boardroom, and it was Steven Spielberg, Michael Crichton, John Wells and representation from CAA. And they pitched it.

Wells: People have different memories. I do know for a fact that Steven was never in any pitches. Now, Steven may well have picked up the phone and called Warren at some point and said “We should do this,” because he was known for doing that. But it was just Michael and I with CAA’s Tony Krantz. We then went out and pitched it.

Littlefield: In that first meeting, they said, “Michael wrote a screenplay. And it is from that screenplay that we think the series should come.” And we were excited.

Wells: It was a difficult process getting this show sold.

Littlefield: On the weekend, we sat down and read the script. Now, Michael was a wonderful writer, but [the script] was kind of all over the place. It was 160 pages, or something like that, with over a hundred characters. Michael's [original] draft was set in Boston. A 24-hour period in an E.R. in a Boston hospital. We had done St. Elsewhere [which was set in Boston] So we just said, “You got to change location.”

Wells: Every broadcast network turned us down. Twice.

Littlefield: But we also knew John Wells was the guy who was going to be doing the series. Like, day in and day out, night in and night out, it was John Wells who we would be banking on.

Wells: [NBC] came back to us and said, “Well, if this doesn’t work, we’ll make a two-hour movie as a backdoor pilot.”

Littlefield: We said, “We are the best home for this show. And if you do this right, it's going Thursday at 10:00. That's what you're aiming for. It's a two-hour pilot. Just make it.”

Wells: There were still a lot of movies of the week on television at the time. So the thinking was: If it doesn’t work as a series, with the Crichton and Spielberg connection [with] Jurassic Park, they could always just run it as a TV movie. They could put “From Michael Crichton and the mind of Steven Spielberg on it,” or something like that, and it would work. But it was about a two-and-a-half year process to actually get the show made.

Littlefield: But what they talked about in that [original pitch] of what they thought they might be able to do was there. It was embedded in that material. And so the roll of the dice was: Could John Wells extract it, and kind of reconstruct it, and bring it to life? And that was a bet we wanted to make.

Strong Vital Signs

With a new script by Wells that made the medical drama aspects of the show more character-driven, NBC had a pilot they were confident in shooting. But, given the passes the show had received, the network still had some reservations.

Littlefield: I knew that, at the end of the day, I could put Steven Spielberg and Michael Crichton's names on it. But I didn't want to pay for failure.

Wells: [ER] was not a slam dunk. West Wing took almost three years to get made. Shameless took seven years to get made, so these are not unusual experiences.

Littlefield: We said, “If you do [the pilot] well, your reward is Thursday night [for the series].” But they wanted a series commitment.

Wells: [NBC] picked the show up for a pilot very late. We didn’t get the call from NBC about maybe doing it as a backdoor pilot until some time in January of that year. Michael was unhappy with the idea it wasn't going to go to series, since that's what we had decided at first, So when people were just offering us the two-hour pilot, he said, “Yeah, I don't really want to do that.”

Littlefield: I also knew that CBS was doing a new medical procedural [David E. Kelley’s Chicago Hope]. They chose to go directly up against us. ABC had a medical procedural, but they didn't have the real estate at ten o’clock. And I said to [Michael and John], “Here's the real estate across the networks. You're not going to do it at Fox. And they don't have any 10 p.m. slots. NBC, we are your home.” And it was months and months and months of them saying, “It's got to be a series.”

Wells: There was a woman who was working at Amblin who knew Michael well from some of the series development, or movie development, that they had done. She called him up and said, “You guys should really do this. They want to do it as a two-hour. Just do it well. Get it done. You've had it for years.”

Littlefield: They just ran out of time. What also worked to our advantage was that John Wells basically could look at his partners and say, “There's no time left. If you want me to do this, I need to run. I need to just hit it.” Everyone had debated the deal for a long time. And finally, they said, “We'll take the opportunity,” and it worked.

To help make the deal and get them to do the show with us. I just said: “Look, we're a network. We have a lot of control. If we can't agree on casting, tie goes to you.” What I was telling them was, “I'm going to do this here, and you're going to make the show you want to make. And I don't know that I'll ever acknowledge that I've given you this power because people will go crazy.”

Wells: We didn't have a lot of money to make the pilot. We were pretty shoestring. We only had about eight weeks to put the whole piece up, to get it on its feet. So it was cast very quickly.

The Doctors Are In

With the late Rod Holcomb signed on to direct, the production team soon went to work populating their fictional version of Chicago’s Cook County Hospital with actors to play medical professionals that audiences would hopefully invest in for several seasons. Those characters included: Chief resident Dr. Mark Greene, his best friend — the rule-bending pediatrician and ladies man — Dr. Doug Ross; the headstrong surgeon, Dr. Peter Benton; his untested protegé, Dr. John Carter; the extremely competent and down-to-earth Dr. Susan Lewis; and the skilled head nurse Carol Hathaway.

Lori Openden (NBC head of casting, 1985-99, from the Television Academy’s Interviews): George Clooney was attached very early on, but everyone else auditioned in my office at NBC.

[Editor’s note: Clooney was unavailable to participate as of press time.]

Wyle: George, out of all of us, was the most experienced when it came to television. He knew TV inside and out; he had done about 20 failed pilots.

Littlefield: We had early casting lists, but George wasn’t necessarily on them. George sniffed out on the Warner lot that this was in the works. He lobbied and pushed and fought to get John's attention, to be able to read and sell himself to John.

Wells: He signed on right when Rod was taking the job. George, who had a deal on the [Warner Bros.] lot, was well known for befriending the secretaries and getting all the scripts. And he read the script and called me up and said, “I really want to do this,” which was problematic with Les Moonves [president of Warner Bros. TV, 1993-95], who was running the studio at the time.

Littlefield: George was on [the NBC and Warner Bros. show] Sisters at the time, with Sela Ward. And, Les, he did not want to lose George.

Openden: We had another pilot that [George] was going to do, I don’t remember the name, but I know it starred Miguel Ferrer (RoboCop), who [was] George’s cousin. And so we heard he wanted to do that show with his cousin because they were really close.

Wells: But he read ER and said, “No, I really want to do this.” Even though it was the second lead, and Les was not enthusiastic about that.

Openden: I was happy because they were both NBC shows. I didn’t really care which one he did — as long as he did one of our shows.

Wells: He came over to my office; he was the first person to audition for the show.

Littlefield: There were a number of Clooney fans in the room. So they were rooting for him. This was George’s big shot.

For Doug Ross, the producers auditioned actors using the character’s most memorable scene from the pilot, where he confronts an upper-class lawyer and mother (Tracey Ellis) over the severe child abuse she has inflicted upon her infant son. This upsetting incident was inspired by Crichton’s own experience, which the author described in his book Five Patients.

Wells: He did the “He’s a little kid!” scene. He had it memorized.

Littlefield: You could feel the room, like, grab their heart, people starting to cry, and then this kind of triumphant joy for George because it was so clear in that moment. Like, “Oh, my God. You're a television star!”

Wells: I called Les and said, “I think [he would] be great for it.” And Les said, “You can't have him.” And then I called George and said, “Well, Les says you can't do it.” And George said, “I'll take care of that.” I don’t know what he did, but whatever he did, he got Les to agree to let him do it.

For the role of Dr. Greene, Wells and his team decided that the best audition scene would be the emotional monologue that Greene delivers during a pivotal scene with Dr. Carter. During the audition process, Wells and others saw how collaborative — and egoless — Crichton was about his script.

Wells: Through the audition process, there were big chunks of things that Michael had written — because he was a novelist, but also a very good screenwriter — that were a little preachy. A little “on the nose.” And he recognized that.

Sherry Stringfield (actor, Dr. Susan Lewis): [Michael] was very intelligent, very laid back.

Wells: He was brutal with his own words. He was not precious. Three or four people [auditioning for Greene] would do that monologue and then leave the room and Michael would go, “Well, that sucks.” [Laughs]. “Anybody got a pen?” And we'd sit there and start to carve stuff up.

Openden: They usually bring us two or three people to the network [to audition], but Anthony Edwards was alone. They brought him to read in my office.

Anthony Edwards (actor, Dr. Greene): It was a great script, but, at the time, I wanted to be a director. I was, like, 31 years old. I'd been doing movies every year for the last four or five years since Top Gun, and I'd always get offered series. I was in a place where I had my first kid and, in a sense, I was really tired of acting.

Openden: It was just so obvious [it should be Edwards]. He was so amazing in that role.

Edwards: I wanted to direct this little movie but my manager and my wife at the time both said, “You should really consider this because it was Spielberg.” And I kind of got it then. So I went in and read.

Littlefield: Anthony came in and did a magnificent read. I mean, the room was silent. My memory is we looked at everyone when he walked out, after doing that monologue, and we just said, “I wish we had filmed it.” It was really impactful.

Edwards: It was just, immediately, the right fit. It felt to me like it was the right actor in the right place.

Openden: Noah Wyle read in my office. It was me, him, Warren Littlefield and John Levey, who was the casting director on ER.

Wyle: I remember it like it was yesterday. I auditioned twice. The audition scene was me putting the I.V. into a cop who had accidentally shot himself, played by Troy Evans, who then subsequently came back and played Frank, [one of ER’s] desk clerks.

Openden: I believe Noah was 23 at the time. His manager sent him the script.

Wyle: I was brought to the network and I tested against another actor named Raphael Sbarge, who's very talented. And I've told this story many times about Raphael, he started to do tai chi in the waiting room. And I got all freaked out because I didn't know tai chi. And he was all Zen’d out, and I was freaking out. And Michael Crichton walked in the room and looked at Raphael freaking Zen-ing out — and me freaking out — and [Crichton] came over to me.

And without saying another word, he just said, “You know, I was recently reading about this woman who lived in Tibet 400 years ago. And she was a potter. And what's interesting about her is — and nobody knows if it was something indigenous to the clay in the region where she worked, or if it's something specific in her kilning process, or if it was a specific glaze that she employed — but many of her works are not only indestructible, but still in practical use today.” And then he turned, and he walked away.

And I kind of shook my head for a second and thought, “What the fuck?” I then realized that he'd just done the greatest service to me. He walked in, and he saw an actor who knew how to relax doing tai chi and an actor who was really not centered. And he said to himself, “I'll take this kid out of his head for him. I'll take him on a little trip to Tibet and introduce him to somebody who used to make pots.” He never confirmed or denied it, but I was so grateful that he had done that. I was so relaxed when I went in. I just went in and got my job.

And after I was cast, and we were shooting, I remember saying to him, “I'm playing you, right? I mean, it's so obvious that you wrote this in '75 after you were a third-year medical student. [Carter is] the third-year medical student. So I'm you, right?” And he'd say, “They're all me. I'm a little bit Ross. I'm a little bit Hathaway. I'm a little bit Lewis.”

Openden: Sherry Stringfield came in, and she was terrific.

Stringfield: I had literal sweat stains on my clothes. Michael was there for my final audition. I walked in there and thought, “I cannot lift my arms up because I am freaking out so badly.” I was very excited, though. I was coming off NYPD Blue. I read this script, and I was like, “This is amazing! This would be a miracle if I got it.” At the time, I was in my early 20s, and when I booked it, I was so grateful. I was like, “Thank God I have a job!” [laughs]

Glenn Plummer (Timmy Rawlings, Cook County General desk clerk, seasons one and 13): I was cast as one of those day players, it was a good job. I was doing [director Kathryn Bigelow’s 1995 film] Strange Days at the same time as I did ER. I was filming Strange Days at night and shooting ER during the day. The only reason I didn't stay on ER was because I had a movie and a TV show going at the same time.

Wells: For Carol, Julianna — if I remember correctly, I believe she had an interesting audition.

Julianna Margulies (actor, Nurse Carol Hathaway): I was in L.A., I had only done two guest spots on Homicide at the time. I got a call from my agent that Steven Spielberg and Michael Crichton were auditioning people for a pilot called ER that Michael Crichton had written. And to go to the Warner Bros. Studios and to the casting call there. But it wasn't for Hathaway. The part I went to audition for was supposed to be the Doug Ross love interest, and she was a recurring character.

Plummer: [Julianna] was amazing. We got along well. She was from New York. She told the most amazing stories about New York life that, you know, they just cracked me up.

Openden: Julianna was cast as a guest star. And when they saw how good she was, of course, they would not let her leave.

But Margulies almost left her audition before it even started.

Margulies: This is a true story. I wrote it in my book, and I'm embarrassed now to say it [...] but I’m a New Yorker. Even though I was a new, up-and-coming actress, I had a lot of respect from the casting directors because they had seen plays I'd done at Yale and Off-Broadway. And the casting process in New York was very different because I was a little bit known, or at least just people treated me nicely. And I had three auditions the day I auditioned for ER. I went into the waiting room, and it was jam-packed. I was waiting for two hours, and I was getting pissed because I was there on time. And no one had come out to check in or apologize, and I just thought, “Well, that feels a little rude,” you know?

And I had another audition in Hollywood. I’m in Burbank, and the time of day it was [to commute], I was feeling worried that I was going to be late. And I don’t like being late. I thought, “L.A. is not for me. I'm out of here.” So as I got up to leave, John Levey, the casting director, came out and called my name. And I said, “Oh boy, this isn't going to go well.” [Laughs]. So I went in, and sitting there was Rod Holcomb and John Wells. Levey read with me. I don't remember if Crichton was in there. He might have been. So instead of reading this love interest of Doug’s sweetly, I read her like a pissed New Yorker, because I was pissed. I just wanted to get out of there. They said, “Thank you very much” [after the audition], and I left.

But John Levey came running out after me and he said, “You're not right for that part.” And I said, sarcastically, “You think?!” [laughs]. I was so sassy — I can’t believe I was like that. But Levey goes, “We think you’d actually be really right for a different role. It's of the head nurse, Carol Hathaway. She dies in the pilot. Would you read for her?” And being the snotty New Yorker that I was, I said, “I don't do cold readings. I prepare for auditions.” And he said, “Great. Here are the sides. Go sit in my office and when you're ready, let me know.” I truly cannot believe he was so kind.

So I went into his office, learned the lines, and I came back in [to audition]. I read Hathaway with a real edge. So I went off and did my other auditions, still pissed. And I thought — I knew — I didn't get that part. But when I got home after a long, harrowing day of trying to navigate Los Angeles — I was renting a room in a house in Laurel Canyon — the phone rang. It was my agent. And she said, “Well, you booked it.” And I said, “What? I had three auditions, which one?” And she said, “ER.” And I was absolutely gobsmacked. I was like, “Are you kidding me?” She said, “You start filming next week.” And that was it.

Openden: Our biggest problem casting this show was Dr. Benton. We actually started shooting without having a Dr. Benton. One of my favorite stories is, I was watching a tape of an old pilot we did, and Eriq La Salle had been in that pilot. And I looked up at one of my associates [...] and said, “Make sure ER has seen Eriq La Salle. He was terrific in that pilot.” So they brought him in.

[Editor’s note: La Salle was not available to participate as of press time.]

Wells: Eriq only had 24 hours to learn his lines.

Openden: That was the last role that was cast.

Wells: He was the last person we cast because he was on another show up in Portland. He showed up to audition in scrubs, I believe. We were very nervous about trying to hire him at the last minute. We started shooting on a Tuesday, and he actually started filming on that Thursday. He didn't even get into Los Angeles until Sunday or Monday because he just finished the other show.

Stringfield: The cast — we were just super stoked and we gave the acting end of it that energy on the show.

Plummer: I don't have a reference as an actor, working in front of the camera, as it being anything but the best time of my life. And I had one of the best times on [that pilot]. As time consuming as it was, I was dead-dog tired, only getting two-and-a-half, three hours of sleep between [Strange Days and ER]. But I had the best time. We all did.

Stringfield: The crew, the cameraman, they were so good. We were all in it together. It was the “perfect storm” of personalities with the actors and the crew. We all had the same humor — endless laughs.

On-Call

With the cast of “24 Hours” in place, the production raced to secure a location to film the pilot as they lacked the time and resources to build a hospital set. The pilot was shot at the abandoned Linda Vista Hospital in Los Angeles’s Boyle Heights, which had ceased operations in 1990.

Edwards: That was our first meeting at that hospital, in a rehearsal. That was the first time I had met the cast. I think we started shooting the pilot on March 17, St. Patrick’s Day, so we did that for two weeks.

Wells: We brought in [medical and tech advisor] Dr. Lance Gentile, who was very involved from the beginning and ended up winning an Emmy as one of the writers. He came on, and he helped grill everybody on the medical procedures. They all learned how to suture and everything in advance. And then we just moved fast because we didn't have that much time.

Wyle: I got really good at suturing.

Wells: We had pig parts around that we’d get from the butcher.

Wyle: The one thing we all had in common, back in the early days of the show, was our sincere desire to try to make everything look as authentic as possible. And it almost became a sort of competition between us to see, if they were going to feature our hands, who could do the procedures the most elegantly. So I would go to the store, and I'd buy all these chickens, and I'd cut them up. And then I'd sew them up and practice at home.

I got so good at it that they started putting me in the background of scenes with a pig's foot because a pig's skin has the most comparable elasticity to human skin. So I sewed up a lot of pig's feet on set. Which, after eight or nine hours under the stage lights, ended up smelling pretty ripe.

Wells: Everybody got to where they started to compete, even with the dialogue. The long monologues of medical jargon. Anthony Edwards would really compete who could do the longest string of stuff.

Edwards: When you read something that's fresh and genuine, it just pops, right? It’s all make believe, but for some reason, when the writing is like that, it just felt so real. And it was super exciting, because it was going to be a huge challenge.

On location, due to necessity and time constraints, director Rod Holcomb would establish the series’ visceral visual style.

Wells: Rod Holcomb, who just recently passed away, is the unsung hero of all of this. He never got enough credit. What people remember about the show, and the way it moved, was Rod's work.

Littlefield: We had conversations with Rod and John about the visceral quality of the material and the need for the show to feel real, but not melodramatic.

Thomas Del Ruth (director of photography, 1994, from the Television Academy’s Interviews): We approached ER as a “dramatic documentary.” We shot a lot of handheld, with a lot of [light] sources that I had created within the existing hospital to create strong, hot beams of light. I overexposed the actors several stops when they would walk under certain lights, and then they would fall into deep shadows. I used a lot of rain effects, and cyans and blues to essentially be almost symbolic of a bruise — the colors that you would see in a bruise on a wrist were the colors that I used in the show.

Wells: We talked about how important it was for us to distinguish the show from Chicago Hope, which came out of knowing that it had already been picked up. I happened to get a hold of the script [for Chicago Hope] and realized we needed to be very different from that. And to do that, we had to really take the audience into this world, drop them into this E.R.

Stringfield: We didn’t have enough time to stage and shoot the pilot in a traditional way. And it turned out to be to our benefit.

Wells: [Linda Vista] had an E.R. in the basement that was shut down. The whole place was shut down. And so when we went down there, it had relatively low ceilings. There was no way to light it other than to use the existing fixtures that were in the place. So Rod and I talked about it.

And Rod said, “The only way I'm going to be able to shoot this down here, because I can't really light it, and we are not going to be able to hide things, is to use this new thing that people are starting to use more of is the Steadicam.” There was no room for the [camera] dolly, or all the gear we’re going to need in the hallway. So Rod said, “If we use the Steadicam, I'll be able to just move around quickly. So let’s shoot it like a documentary. We’ll shoot it fast.” That was all Rod.

Del Ruth: It was the first time that a Steadicam had been used in television [to that extent]. We would do a nine-minute [take] that was shooting 360 degrees in 25 different rooms, and long walks and talks, all within the same take.

Littlefield: [John and Rod] turned it into an action thriller. And so the camera was flying all over the place.

Margulies: Before I did the pilot of ER, the Steadicam, to me, was a phenomenon. I had never seen one. I would watch how they did the shots and I remember a light bulb going off thinking, “Oh, the Steadicam is the seventh character in this show.”

Littlefield: The audience was witnessing visuals of trauma on an E.R. table and in an operating room that they had never seen before. This was not Marcus Welby, M.D.

Edwards: I just have such a clear memory of being completely lost for the shooting of that pilot. Because you didn't know where you were or what it meant because you didn't didn't know how an E.R. worked.

Wyle: The thing that Rod did, and I'm sure John gave him the credit for this already, is that Michael had written an extremely technical script that was really terse and unsentimental and really professional and didn't pander to the audience at all. But, also, it didn't really have much in terms of interpersonal relationships. So Rod really designed those with his camera. And he really kind of made them come into full force.

One memorable scene in the pilot that showcases the emotional payload of Holcomb’s visual choices occurs when, after she attempts suicide, Nurse Hathaway becomes a patient at her place of work.

Wyle: After Hathaway's brought in having O.D.'d, it's the way that [Rod] shot those close-ups of everybody looking around the room that made you miss Hathaway. She only had a couple of scenes. But it was the way that everybody reacted to her not being there that made her character so valuable, and eventually so popular, that they had to bring her back from the dead.

Wells: Hathaway was dead at the end of the pilot. Her death scene was shot. It exists.

Margulies: The only reason my character lived was because Rod Holcomb shot my quote-unquote "death”-slash-non-death through Doug Ross's eyes. It was all through his lens, and that's what elevated the character. It wasn't anything I did in the pilot. It was the way it was shot, and it elevated the importance of [Carol] to the Doug Ross character.

Wells: There was just so much chemistry between [Marguiles and Clooney], so she was resurrected. When I brought that up with Michael, I said, “Everybody really loves it, and I think she needs to live.” And he said, “She can't live. Everything we said about her, she's dead as a doornail.”

Margulies: I remember George calling and leaving messages on my answering machine. He’d be sitting with [Warren Littlefield and John Wells] at the upfronts and they said something like, “We don’t think Carol Hathaway is going to die.”

Wells: We had to reshoot part of [Hathaway’s death scene] because she was very dead. She only lived months later. Actually, I had to call Julianna up and say, “Hey, you want to be a regular?”

As production on the pilot continued, Wells realized some potential pain points that could impact the shoot and the series long-term.

Wells: With our visual style, I was very concerned that the actors were going to have a tremendous amount of medical dialogue to do.

Wyle: It’s famous, that long “walk and talk” that Benton and Carter have to do in the pilot. Where Benton is basically giving Carter a tour of the E.R. It took 22 takes. We were shooting with film back then, so film magazines were kind of precious. You didn't really want to waste them. And we were on the last magazine — the last one that we had on the whole set — when he got it.

And just as an example of how playful we were to each other, George and I teased him so mercilessly that it took him so many takes to get that thing out of him. And we would walk past him and make this little sign on our chest for “22” and just shamed him mercilessly for about a week or two. And then they wrote one of those long-ass monologues for me. And Eriq could not fucking wait to crush me over it.

One of the pilot’s most famous monologues occurs in a pivotal scene between Carter and Dr. Greene, set in the hospital’s rain-slicked ambulance bay.

Wyle: That wasn’t originally set in an ambulance bay. That was in, like, this weird alleyway outside the Linda Vista Hospital. And that shot of Carter on the curb, reflected in the puddle? It’s so iconic for the show. It made it into the opening titles!

Wells: How did we get that shot? It rained. Rod was out there and saw the reflection and shot the reflection. But that was him, a real artist and a tremendous stills photographer. He was always looking for those kinds of photogenic opportunities, those ways to tell the story.

Trauma and Recovery

With shooting on “24 Hours” complete, the production went to work editing and screening the pilot for test audiences as well as network and studio executives — including the late Don Ohlmeyer, NBC’s West Coast president from 1993-99.

Littlefield: When you have network research on your pilots, it can be a brutal day. And all your hopes and dreams just turn to crap.

Wells: The movie Speed had come out the summer before, and the note I kept getting was, “People enjoy watching Speed once. They don’t want to see it every week.”

Littlefield: All of us at the network loved and embraced it, but Don Ohlmeyer really felt assaulted by it. It turned into a power play. Kind of like, “They didn't listen to me.”

Don Ohlmeyer (from the Television Academy Interviews): I had some very strong reservations about whether the audience was ready for something that powerful.

Wyle: Can you imagine two more different human beings being partners than [Littlefield and Ohlmeyer]? I mean — Don comes from sports. Their backgrounds were totally different.

Wells: The junior executives would come down [to set]. We never saw Warren or Don or anybody. And those junior executives were Kevin Reilly, David Nevins and John Landgraf. They would come down and eat with us in this crappy cafeteria that we had in this old closed hospital, and they were catching a lot of flak from their bosses that we weren't really taking their notes. Especially Don’s.

Littlefield: [Don] walked out of the screening at the network. And everybody else was glued to it in the screening. They — John and Rod — did something that was not what Don would have done. And somehow, that became like a personal battle.

Ohlmeyer: I actually loved the pilot. I just felt that there was just too much of all that medical mumbo jumbo.

Wells: The network was very concerned that the audience was going to get lost in all the medical [jargon] if we didn't tell them what was going on. And Michael and mine's argument back was always, “Trust the audience.” You could turn the sound off on these scenes and know what's going on. You don't actually need to know the specifics of the language to understand. You're following emotionally what's happening, how people are reacting — how the doctors are reacting to what they're asking for. But we had lots of conversations in those first four or five months before the show went on the air about all the medical dialogue.

Littlefield: I went to Don’s office, and I said, “Look, we're going to have the notes meeting on ER. We're going to give feedback, and you're not invited to that meeting. You shouldn't be a part of that because, obviously, you've got some other agenda.”

Wells: We waited about an hour after the [first network] screening for them to come and give us notes. Finally, Warren comes into the room and says, “There really isn’t much point in giving notes right now because Don is never going to put it on the air.”

Littlefield: Ultimately, Don stood down, but it wasn't without drama.

Wells: Don was very unhappy that we didn’t address his notes — about the language, things moving too quickly, how there were too many characters and storylines. And all of that would become kind of the hallmark of what we were doing.

Littlefield: ER was the highest-tested drama in the history of NBC. And there were five leading characters, who were off the charts. You hope to get one lead that emerges in an ensemble. There were five that emerged. And the response was quite good.

The positive response to the pilot continued up to and including the 1994 upfronts, where NBC flew the casts of both ER and Friends to New York City to attend NBC’s annual event where potential advertisers would get a glimpse of the network’s fall lineup.

Wyle: Originally, the plan was to air [the show] Friday nights at 10. The death slot. But that plan changed when they tested the pilot, and it only got better with what happened at the upfronts.

Stringfield: It was me, Anthony, George, Noah, Eriq and, I think, Julianna [at upfronts]. That was the first time I had seen any of the pilot. It was like watching a movie.

Edwards: We had never seen anything cut together until then. And I think that’s when we first thought, “This is special.”

Wyle: We're in the wings of Avery Fisher Hall, and they screened clips on this giant screen.

Edwards: We’re sitting there, watching something like 10 or 15 minutes of footage that they cut together. George and I looked at each other, and we're like, “Holy shit, this is good.”

Wyle: And when they stopped [the footage], there was silence, and then the whole place — they were clapping and hollering. They just loved it. And I remember Tony turning to all of us and saying, “Here we go.”

Edwards: We had a fun time afterwards.

Stringfield: We hit the town. We were all having dinner. We went dancing. It was just so much fun. We were like, “The show's going to be huge.”

Littlefield: We created a one-minute spot that we ran during the [series] finale of L.A Law. We knew what we were sitting on, so we stuck it right in the heart of that finale and then studied the audience reaction to the spot. And they went crazy. The intent to view was so high — it was like, “Oh, my God.” And that's it. We knew it was going to be great.

Post Mortem

On Monday, September 19, 1994, 23.8 million viewers tuned in for the airing of the pilot from 9 p.m. to 11 p.m. ER would then move to its official slot, Thursday night at 10 p.m., on September 22. The series remained there for its entire 15-season run, anchoring NBC’s block of Must See TV programming on its way to becoming the network’s third longest-running drama.

Wyle: This was my first show. I didn't really have a frame of reference for what a hit show was. So I remember asking George whether a 40 share was good and him saying, “Yeah, buddy. That's pretty good. Basically, it means that one out of every two TV sets in America was watching you last night.”

Littlefield: John Wells said to me, “I can't tell you how many episodes we would have to add up to get to a 40 share of the work I've done previously.”

Wells: All the way up to when [the pilot] premiered, [the network] still kept saying to me, “Nobody wants to watch Speed every night.” And particularly not on a medical show. That many people can't die, et cetera. And we sort of stuck with it. So when it went on the air, Warren — to his credit — called me up really early on a Friday morning when he got the East Coast numbers. He said, “Yeah, forget what we said. Just go do what you're doing.”

Littlefield: ER premiered on a Monday night against a big Dallas football game that I was like, “Oh, dear God, we're going to get killed.” But we did great. And when we went into Thursday, within three weeks, we went from a 40 to a 45 share. And, strategically, because we were kind of pissed off that advertisers didn't respect us more — we had all this available airtime to sell [for the pilot]. At the upfronts, advertisers said we were a 21 share. But, now, on Thursdays, instead of selling it at a 21 share, we were selling it at a 45 share. So… their loss.

Wyle: I remember going to New York to do my first talk show, which was Regis and Kathie Lee. And as I came out of doing the show, somebody thrust that Newsweek magazine at me that had all of us on the cover. I thought it was one of those joke [photos] you can get at, like, Magic Mountain with a fake byline over a photograph. And I sort of said, “Oh, I got to get one of those.” And the guy pointed to the news kiosk that was just full of them. That was just the beginning of when we knew we were on to something.

Stringfield: I had never experienced anything like it. And it is a great feeling to step back and see how all of us were part of literally making TV history.

Edwards: We were just so excited to go back to work, to keep working. And it was wild. All of a sudden — this life, it just became this full life.

Littlefield: The cast and crew were fueled by the success and impact they were having. As an example, G.E. was our corporate parent. The show had an imaging unit there in the [E.R. set]. And Jack Welch, who was the then-chairman of G.E., called up and goes, “The imaging unit is not a G.E.” And I say, “We don't own the show. We don't produce. What do you want?” He goes, “We'll replace it. Just tell us where it needs to be. We will send one.” And they did. Within, like, two days, there was a G.E. machine installed on the set. And it was not a fake one. No one said we had to feature the logo or anything on the show. All [Jack] said was, “Our employees love the show, and it’s painful for them to know it’s not their equipment.”

Wells: [NBC] stuck with us for all those years, 15 seasons. So no complaints.

Margulies: George used to say, “Sometimes the stars just align the right way, but very seldom.” And the stars aligned, and it was magic.

ER is now streaming on MAX and Hulu.

Click here for more Television Academy video interviews featuring key ER cast, crew and creatives.

See more articles celebrating ER's 30th anniversary.