Legend has it that the first Jeopardy! clue, which was never televised, was "5,280."

It was probably given at about 30,000 feet above sea level, but that's just an educated guess. We do know it was spoken on a plane en route to New York City from Duluth, Minnesota.

Aboard the plane was Merv Griffin, once a big band singer and an actor, now better known as a talk show host and game show producer. Seated beside him was his wife, Julann. They were talking about concepts for a game show. Julann suggested a twist on the usual format — players would get the answer and then they'd have to come up with the question.

For example, she said, "5,280." And the question would be, "How many feet in a mile?" Merv loved the idea. So did NBC; the network bought it just from his pitch without even making a pilot. The working title was What's the Question? but the name was changed to Jeopardy! by the time it premiered on March 30, 1964, with host Art Fleming and announcer Don Pardo.

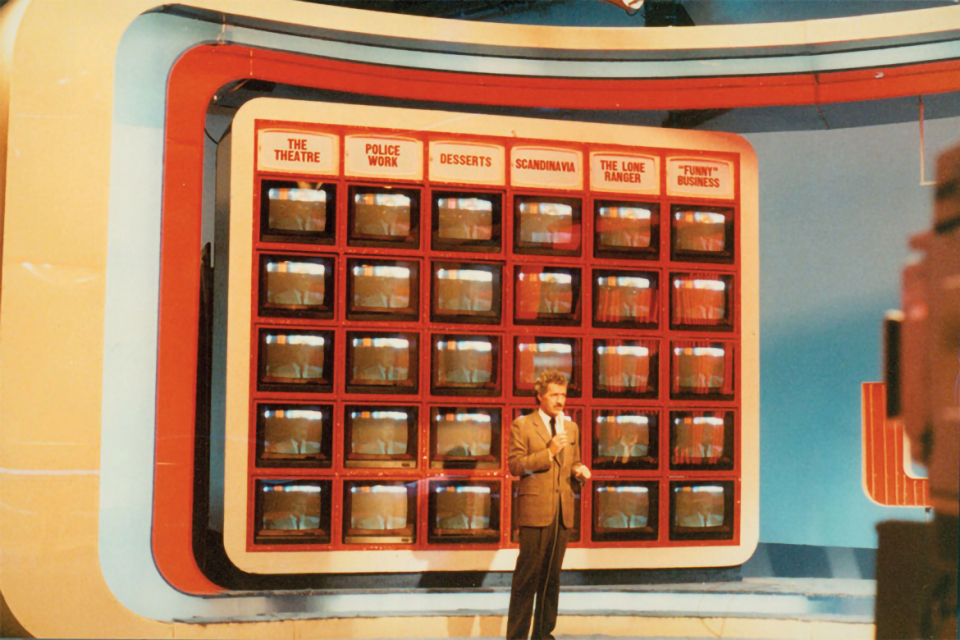

Just like today, it consisted of a Jeopardy! round and a Double Jeopardy! round — each with five clues in six categories — followed by Final Jeopardy! The value of the first clue was $10. Stagehands pulled the printed cards to reveal each clue. The first Jeopardy! champion was Mary Eubanks from Candor, North Carolina. Her winning total was $345.

The original version of Jeopardy! ran until January 3, 1975.

That might have been the end of Jeopardy!, but, ironically, it was saved by another game show — Wheel of Fortune.

Also created by Griffin, Wheel of Fortune had been a daytime staple on network television since 1975. In the fall of 1983, it was brought to the syndication market, where it quickly became an even bigger hit.

The executives at King World, the company that distributed Wheel of Fortune, asked Griffin if he had another show to be a companion in syndication. It would be far more profitable if they had two successful shows that could be sold together as a one-hour block.

Thus was born the current syndicated version of Jeopardy! Alex Trebek was hired to be the new host. Jay Stewart was the announcer on the pilot; Johnny Gilbert took over after that.

Stations that carried Jeopardy! were not immediately convinced of its appeal. "In Los Angeles and some of the big markets, it was on at two in the morning," Trebek recalled. "As it proved itself, it got better and better time periods."

For the first three years, Trebek did double duty as host and producer. He traveled from city to city, promoting the show and offering tryouts to people who had expressed interest in becoming a contestant. At each stop, he tried to drum up interest for this new version of an old favorite.

At the same time, Trebek puzzled over how to modernize the show with new technology. Instead of stagehands pulling cards, projectors displayed the clues on screens. But that still looked clunky, Trebek remembered.

"We needed to get a computer that could put the clues on the screens," he said. Fortunately, the Los Angeles CBS station had a secondhand one to sell.

Jeopardy! was reborn on September 10, 1984. The first three contestants were Frank Selevan, an advertising copywriter from Miami, Florida; Lois Feinstein, a freelance copywriter from Plainview, New York; and Greg Hopkins, an energy demonstrator from Waverly, Ohio.

"Welcome to America's favorite answer-and-question game — Jeopardy!," announced Trebek. "You know how we play it. We provide the categories and the answers, and then it's up to our contestants to give us the right questions."

Hopkins selected "Animals" for $100 (values were doubled on November 26, 2001). "These rodents first got to America by stowing away on ships," Trebek read. Hopkins entered game show history books by giving the new show's first correct response: "What are rats?"

During the conversation break, Trebek asked Hopkins what an energy demonstrator does. Hopkins produced a balloon, intended to represent a uranium atom. He blew it up, twisted it, and then made it explode. "Greg," said a bemused Trebek, "try and relax."

It was good advice. By the end of the show, Hopkins had become the first champion, winning with $8,400. Feinstein, who finished second, got a vacation at the Ingleside Inn in Palm Springs, California, and a set of luggage. Selevan brought home his-and-hers Wimbledon tennis rackets.

Office space was tight in the early days of Jeopardy!, but that wasn't the biggest problem. Of greater concern was a meeting a couple of weeks into the season. King World executives told Trebek they thought the clues on the show were too difficult.

"We were taping weeks in advance," Trebek recalled. "I said, 'Okay, I'll ease up on the material.' Three or four weeks later, they came back to me and said, 'Oh, you did a good job. It's a lot better now.' In reality, those shows already had been taped. I didn't change anything. I didn't agree with them. I didn't tell them that. I just said I'd do something."

Jeopardy! has always been a work in progress. One significant change occurred right after the first season.

Initially, contestants could buzz in with a reply at any time after a clue was revealed. However, while the camera focused on the clue being read, off camera, the first player would respond by buzzing in. By the time there was a shot of all the players, a second player might have buzzed in. Viewers thought Trebek was calling on the wrong player.

So, to avoid viewer confusion — and to allow the at-home players a better chance to "play along" — contestants had to wait until the entire clue was read.

The first tournament on Jeopardy! was the Tournament of Champions in 1985. Following a format invented by Trebek, the typical Jeopardy! tournament starts with 15 players. After one week, nine are left — the individual champions from each day and the four non-champions with the highest scores.

During the second week, after three games, the number of players is reduced to three. Those three contestants play two games over the next two days. The winner has the highest combined point total for the final two games.

From the onset, second-and third-place players were not allowed to keep their "accumulated" cash. That was done to discourage conservative play by contestants afraid to risk the cash they had earned and to keep the Final Jeopardy! round interesting.

Instead, non-winners received vacation packages and merchandise. In 2002, the prizes were discontinued and Jeopardy! began awarding $2,000 to players who finish second and $1,000 to those who finish third.

On September 8, 2003, at the beginning of the 20th season, a rules change ended the five-game limit on Jeopardy! champions. From then on, champions played until they were defeated. Later that same season, Ken Jennings — a software engineer from Salt Lake City — began his 74-game win streak, the longest by far in the show's history.

The son of an international lawyer and a school librarian, young Ken was reading at age two. He had an unquenchable thirst for knowledge about, well, just about everything. By age seven, he could tell you the life story of every U.S. president.

During his adolescence, his family lived in South Korea for about a decade. When he returned stateside and attended Brigham Young University, he majored in English lit and computer programming.

Still, Jennings wasn't brimming with confidence when he stepped up to the podium for his first game. "I really didn't know if I was good at Jeopardy!," he confessed. "That's not false modesty. I really had no idea. But then I realized in the first few minutes that, at a bare minimum, I can hang with the people here today."

Trebek said he didn't form an impression of Jennings until perhaps the eighth or ninth win. "I don't really remember the early games. Initially, he was just another player who was doing well," he said.

As Jennings gained momentum, Trebek began to size him up. "I liked him. He had a sense of humor. I respected his ability to really understand how to play the game — when to put pressure on his opponents, when to make a big bet on a Daily Double. And he was very bright. It's no accident that he won 74 games. He knew his stuff."

Meanwhile, ratings were going through the roof. The Associated Press reported that average viewership rose from 9.6 million in June 2004 to about 15 million in July. By the time Jeopardy! began its 21st season on September 6, Jennings — or "KenJen," as he became known — stayed on the streak. At his 70th game, he reached $2.3 million in winnings.

In his 75th game, Jennings was challenged by Nancy Zerg, a former actress turned real estate agent. Many of the players during his streak were intimidated by his success. They kept their distance from him during the orientation before the games were taped. Not Zerg.

"They were afraid to talk to him," she recalled. "He was sitting off by himself, and I thought this was silly. So I went over and said, 'Hi,' and we started talking. He was really funny and obviously incredibly bright."

That was the day the bullet in the chamber found Jennings.

During his streak, he had answered 83 percent of all Daily Doubles correctly. This game, he missed both. Even so, he went into Final Jeopardy! ahead of Zerg, $14,400 to $10,000. (The third contestant, David Hankins, had been eliminated with a negative score.)

In the category of Business & Industry, the final clue read: "Most of this firm's 70,000 seasonal white-collar employees work only four months a year."

Zerg wrote quickly, smiling with a bit of confidence, in contrast to Jennings's pensive gaze. A moment later, the correct response appeared on her screen: "What is H&R Block?" With a wager of $4,401, she was now one dollar ahead of the reigning champion. Everyone's attention turned to Jennings's podium.

"What is FedEx?" the screen read. Jennings had always prepared his own tax return. Even if he had more time to think about it, he said later, he never would have come up with the right response. He felt a quick sting of disappointment. For the first time in six months, the face on the monitor that showed the winner wasn't his.

Jennings's streak never will be matched, Trebek declared. "It was the perfect storm. It just worked. We've had very good champions since then. Our material has changed, too. We are more into pop culture. Ken came along at a time when the material was different. The opposition was different."

And what does Jennings think about the chance someone will break his record?

"I do not believe it is impossible to beat that record," he said recently. "If I'm the only person who thinks that, maybe it's because I'm the only person who's been in that situation. But I know it can be done."

Reprinted with permission from The Jeopardy! Book of Answers by Harry Friedman and Barry Garron © 2018 Jeopardy! Productions, Inc., available at Amazon.com.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 11, 2018