The Interviews: An Oral History of Television officially launched in 1997 as The Archive of American Television to capture on video the reminiscences of the pioneers of the television medium. The name was later changed to reflect the fact that as time went on, those interviewed could also be involved in international television programming, and the roster of interviewees expanded to people who have influenced television in their own respective eras.

As of now, there are 940 interviews in the collection, most of which are digitized and available for viewing online here, with more to follow. The collection is searchable and cross-referenced with other interviews by such criteria as topics, people's names, professions and television programs; if a particular show is mentioned, for instance, the user can search for other interviewees' mentions of that show.

A detailed account of the program's founding is available here. The collection is currently undergoing a multi-year preservation process in collaboration with the USC Digital Repository, aided by a $350,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

THE INSPIRATION — DEAN VALENTINE

In August 1995, Dean Valentine, then president of Walt Disney and Touchstone Television and now an avid art collector, suffered the loss of his friend Danny Arnold, an Emmy-winning writer and producer whose credits included That Girl, My World and Welcome to It and Barney Miller. He realized, with regret, that the stories Arnold had told him of his many years in television were also lost with Arnold's death, those first-hand accounts never having been recorded. Dovetailing with that regret was Valentine's introduction to Steven Spielberg's Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, which videotaped interviews with Holocaust survivors about their experiences. That same concept, Valentine thought, should be used to record television history, told by those who created and lived it.

I grew up watching American television. As an immigrant kid from Romania, the television of the '50s and '60s and '70s was the window into this country for me, in a way, and so I've always felt an emotional attachment to it that went beyond just entertainment. That kind of overlaps with the Shoah Foundation, because when I was given a tour of it by Steven Spielberg, it really rang a number of bells, as my parents themselves had lived through the Holocaust in Romania.

So, it was this notion that the past really should be preserved, that rang clearly in my head as part of my own upbringing and experience: the coming together of those two strands led to the Archive. Especially with the Shoah technology, that pointed to new ways of preserving the past and new tools that would enhance it.

I felt that as these men, who were the founding generation of television, were hitting their mortality as they hit their seventies, eighties and nineties, a lot of their memories were going to go with them. Nobody was keeping track of what had happened in this concentrated period of thirty, forty, fifty years, and in this medium that really changed the world and changed America. I felt that there should be some way of recording it.

The Archive was focused on the past but was also meant to be a living thing to keep going, under the assumption that change would be constant and new modes of television would keep springing up — which indeed they have. Someday there'll be the archive of streaming, all the people who were involved in making streaming happen in some compelling way.

GREENLIGHTING THE PROJECT — RICHARD FRANK

Valentine brought his idea of the need to preserve such a wealth of industry information to his boss at Disney, Richard Frank, who was then also president of the Television Academy; he is now the owner of two California vineyards. Frank greenlit the project.

Of course, we needed to start the Archive. Around this time, Steven Spielberg was developing a computer program which would attempt to allow Holocaust survivors to connect with each other by matching names, places and stories from individuals and then connecting them with each other. For example, someone who mentioned a street name in Poland would be connected with someone else who had mentioned the same street.

We reached out to Steven to see if we could use the program he was developing for his Holocaust project for the Archives. As usual, Steven said yes. Once we had this new technology, we then had the ability to launch the project.

That was when I reached out to Tom Sarnoff, who at the time was heading up the Television Academy Foundation, to see if this was a project in which he wanted the Foundation to be involved. The Foundation would be where we could raise money to support the project. Tom said yes, and the Archive became a reality.

My intention was always to raise awareness of this rich vault of television history, told by those who created it. How did these founders of television start their careers, and how did they become successful? The interviews get to the root of who these people are. This is the history of television from the horse's mouth — interviews you could never get again.

THE ACADEMY FOUNDATION — THOMAS W. SARNOFF

Entertainment executive Sarnoff was then chairman of the Television Academy Foundation and is now Foundation chair emeritus.

My immediate reaction at the idea was excitement. Rich Frank and I were very impressed. I made sure that somehow the Archive would be part of the Foundation, and frankly, I did so because the Foundation was very young, and I thought it would be a tremendous feather in the Foundation's cap. It's my humble opinion that the Archive is the most thorough program in establishing the history of television. I'm very proud of what we accomplished.

AN EARLY SUPPORTER — MARGARET LOESCH

Producer-executive Loesch is currently a Foundation board member and Kartoon Channel executive chairman.

I was a governor of the Academy when Dean introduced the idea at a meeting. Dean was very forward thinking; I was always impressed with his big-picture view of opportunities and of the business. We embraced the idea immediately, because we were losing people every day. And I think it may have tied into some of the thinking that, for the people who were being inducted into the Academy Hall of Fame [for their contributions to television], wouldn't it be great if we had these interviews with them? For many of us, it was a natural step beyond the Hall of Fame.

We believed that professors would embrace it, teachers would embrace it, classrooms would embrace it and it wouldn't even have to be [only] for film and television study. These are pioneers, period. And I thought that people outside of the industry would also find it interesting, educational and informative.

If I were a young person, or anybody, and I was looking for a way to do things, I would go to The Interviews and listen to what people said about how they did it. There are very many ways to be successful in our business, but there's some commonality of hard work and commitment and perseverance. I tell people all the time that the biggest difference between a person who's successful and one who's unsuccessful in our business is, the successful people don't give up.

COMPILING THE FIRST INTERVIEW SUGGESTIONS – JEFF KISSELOFF and RICH HALKE

Valentine recruited Disney executives Janet Blake and John Litvak to help with the project, and they in turn reached out to two people: Jeff Kisseloff in New York and Rich Halke in Los Angeles. Kisseloff was the author of the 1995 book The Box: An Oral History of Television, 1929-1961, a collection of interviews with people who worked in early television; he has since written several more books, including one awaiting publication about accused U.S. spy Alger Hiss. Halke, then a writer-producer on the Touchstone sitcom Misery Loves Company and today a writer and web festival creative, was well versed in both early television and comedy history; he was cofounder of the "Sundays at Seven" group which hosted prominent comedy writers for dinner and conversation. Both men compiled lists of interview suggestions for Valentine to present to the Academy, some of which were included in the pilot program of six interviews and others conducted later as the project progressed. And both have themselves since been interviewed for The Interviews.

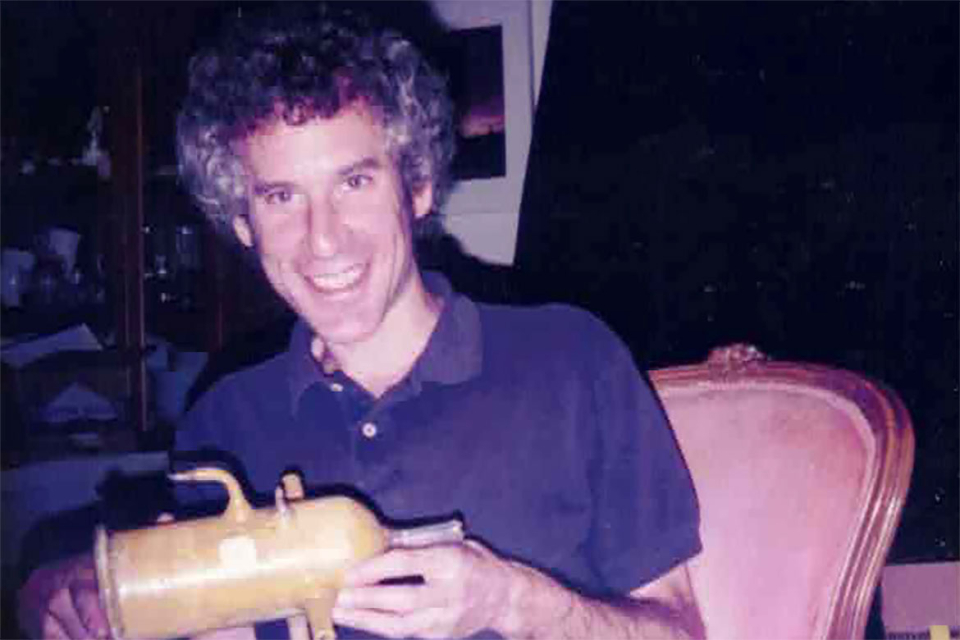

JEFF KISSELOFF

Janet Blake called me and said, "We're thinking of starting this archive. We have this idea. We read your book. We want to do exactly what you did. Tell us how to go about doing the interviews, and who we should target." They wanted to know about doing oral history. We made an appointment and sat down and chatted. Then Michael Rosen [the project's first executive producer] got in touch with me, and I spent a lot of time with him making lists of people who they should see first. Because in all my years, one of the big lessons I've learned is that it's really hard to interview people when they're dead.

I got [and interviewed] "Pem" Farnsworth [real first name Elma, who helped her late husband Philo T. Farnsworth develop television]; Dick Smith, who was the most famous makeup man in Hollywood; Loren Jones, an NBC technical engineering genius who helped invent television and Reuven Frank, who had been a president of NBC News.

Pem was a really big deal, a two-day interview at her home in Salt Lake City. [The interview runs seven hours.] You couldn't have an archive without her. At one point, she reached over to the side, and she handed me this yellow tube. It was the first tube Philo Farnsworth ever made for television, and I was holding it. That was just, "Wow."

I can't remember anybody ever turning us down, but I think there was some hesitancy on the part of actors or actresses to make sure they were lit well. Michael [Rosen] spent a lot of time on the lighting and the way people were presented. I think that's one reason the archive is such a success in getting people, because they know they're going to be treated well by the camera, which is important to them. Michael wanted to be professional, and to show people at their best.

RICH HALKE

Danny Arnold died the 19th of August, 1995, and I handed in my list November 1, so there wasn't that much time between when it happened and Dean got the idea. I wrote a letter with the list, noting people with different areas of expertise whom I felt were all necessary. They included Lucille Kallen — Mel Tolkin's writing partner on Your Show of Shows — and Madelyn Pugh Davis and Bob Carroll, Jr., who wrote every episode of I Love Lucy. I noted then, "Kallen and Davis are the only surviving female comedy writers from TV's Golden Age. If the experiences of these women are not preserved immediately, the history of television comedy from a female perspective will be greatly lacking."

Milton Berle was on the list, but they couldn't get him. So, I told them I'd get Milton, called my friend Dan Pasternack, who knew Milton, and told him to convince Milton, which he did; Milton insisted that Dan be the one who interviewed him. I'd also give them numbers and contacts for people on my list, many of whom had been guests of our Sundays at Seven group. One on the list, Kukla, Fran and Ollie director Lewis Gomavitz, was a friend of my landlady, so she gave me his home number.

Dan became the star interview guy. I also got [comedy historian] Jeff Abraham in, because he was in our Sundays group. I never pushed to do any interviews because I was trying to get the best people, and they were the best people in my mind.

THE EARLY INTERVIEWS — DAN PASTERNACK

Following his interview with Milton Berle, producer-turned-professor and preservationist Dan Pasternack went on to conduct several dozen more interviews, among them Allan Burns, Billy Crystal, Michael Eisner, Whoopi Goldberg, Bob Newhart, George Schlatter, Sherwood Schwartz and Jonathan Winters.

Milton and I were very fond of each other. And that, as much as anything, made interviewing him fairly easy and fun. After countless lunches with Milton at the Friars Club, I already knew a lot of his great stories. I just had to cue him and let him go.

I have incredibly vivid and fond memories of shooting that interview, which was recorded in a suite at the Hotel Bel-Air. We began by lighting a pair of cigars on camera, so our fun dynamic was evident right from the get-go.

Because these interviews are intended to memorialize history from a single person's perspective who lived that history, they are not meant to be rambling, free-form conversations. They are exhaustively researched ahead of time, thus making it incumbent upon the Academy and the interviewer to be incredibly prepared with information to guide the subject through their story.

I've been very hands-on in compiling the research and composing the questions for every interview I have conducted. This was before the internet made research much easier; information had to be dug out of books, old magazines and newspapers, and cross-checked by calling multiple sources. It was a combination of fun detective work and embarking on a grueling scavenger hunt.

When the project was first greenlit by the Academy, my research led me to Nick Stewart, the last surviving cast member of the Amos 'n Andy TV series. While hindsight does not look particularly favorably on that series, as one of the first and only series in early TV to feature an all-Black cast, its historical significance could not be overlooked. And as one of the only living African-American performers at that time whose story went back to those early days, Stewart was a perfect example to me of exactly why the project was created. Because without his inclusion, an entire perspective might otherwise go unrepresented. And even though he was in failing shape [he was 87 at the time], I was thrilled that I was able to find him and conduct the interview.

THE FIRST EXECUTIVE PRODUCER OF THE INTERVIEWS — MICHAEL ROSEN

Filmmaker Michael Rosen, now head of his company August Road Entertainment, was the first executive producer of what was then the Archive of American Television; the position is now called director.

When Dean Valentine approached me in 1996 with his inspired idea to apply the Shoah Foundation's concept to the history of television, it all made sense. As a filmmaker, I knew the power of personal storytelling told from different points of view. He hired me to produce the pilot stage, and we all went to work.

However, we quickly realized a significant challenge: the TV business had been too busy growing to stop and document its own history. Finding any resource was scarce. Fortunately, a few books helped pave the way. One was The Box: An Oral History of Television by Jeff Kisseloff, who interviewed hundreds of early TV pioneers. And there was Marvin J. Wolf's Beating the Odds, an autobiography of ABC founder Leonard Goldenson, who also became the Archive's first interviewee.

Legendary executive Grant Tinker and award-winning documentarian David L. Wolper joined as honorary co-chairs to fundraise and legitimize the project within the industry. They were critical to our early success.

To complete the pilot, we conducted our first six interviews, edited a concept video hosted by James Garner and Noah Wyle, and began pitching around town.

In March 1997, I was hired as executive producer to build the Archive from the ground up. The idea of documenting the lives and careers of television legends at this scale was exciting beyond words.

I hired researchers to ensure the research was extensive and accurate and created an interview list of questions so that every interviewer could sustain a three-to-five-hour interview with a TV legend. We also created an extensive timeline of the person's life and career, which was usually ten-to-twelve pages, typed.

From the start, I approached everything as a documentary filmmaker. I made sure we filmed each interview with the highest production value — like the best of television — that would stand the test of time.

Early on, we accomplished our first goal: to be the world's most comprehensive repository of interviews on television history. By 1999, we had surpassed the first 100 interviews and had over 500 hours of content, in two years.

THE INTERVIEWS EXPERIENCE — JONATHAN MURRAY

Producer-writer-director and Academy Foundation vice chair Jonathan Murray, who with late partner Mary-Ellis Bunim created the genre of reality television with The Real World in 1992, is the current chairman of The Interviews Committee, which focuses on broader issues and fundraising related to The Interviews; there is also a separate Interviews Selection Committee.

I first became aware of The Interviews when I was asked to be interviewed. When it was explained to me what it was, I thought it made perfect sense. I think it's critical that we, as an industry, record our history. And we should, for the next generation of people and future generations to be able to hear firsthand, from the people who were there, what it was like and what went into creating the programs that not only entertained us, but sometimes influenced a nation.

And it's not just about the person being interviewed; it's also about the people they came in contact with. [Costume designer] Bob Mackie did an interview. But then you look at Carol Burnett's interview, and she talks about Bob Mackie, and Bob Mackie talks about Carol Burnett. So, you have these different viewpoints. The more points of view we can get from different people involved with our history, the more thorough our understanding of it will be.

My experience doing my interview was wonderful. [Murray was interviewed by Stephen J. Abramson in December 2011.] I had been asked a number of the questions before, but this was a much more thorough approach to my career and my observations of what it was like to be at a real tipping point in the industry for nonfiction storytelling. So often, we're approached for interviews, and you don't get the sense that someone's really done their homework. Well, the person who interviewed me had done their homework. They really had taken the time to come in prepared and did a depth of interviewing that I hadn't experienced before, which I think is critical when you're trying to preserve history. There was a seriousness, a thoughtfulness.

THE EVOLUTION AND FUTURE OF THE INTERVIEWS — JENNI MATZ

Jenni Matz has been director of The Interviews since 2017.

Oral history is a specific type of interviewing style; it is not like a journalistic approach. We take care to enable the interviewee to present their story without prompting or leading questions. We take care not to interrupt the speaker or dispute their version of events. We do not censor or editorialize but present the interview in its raw form. We do allow the interviewee to view their interview before it is published on our website and omit anything from the record they find inaccurate or prefer not to be made public.

There are recurring themes through the years. Many of our interviewees are self-made success stories and overcame a lot of obstacles professionally and economically to make their way in the business. I find personally that the more tenacious and willing to work any job at all to "break in" often is a common thread among the most commercially successful interviewees. Among actors, almost every single one, when asked to give advice to aspiring actors says, "Don't do it. Do anything else unless you have to," because becoming a successful actor is so competitive and full of so much rejection.

People these days are a bit more savvy about the public access to these interviews and how they will be used. In the first ten years or so, since there was no website, people did not have a way to imagine or anticipate a user being able to watch the entire interview this way, and so easily. Now, in the age of immediate access, they realize that what they say will be online forever, so they may take a bit more care to vet their stories.

Because the television industry in its nascent days of the 1940s and '50s was predominantly white males, many of the stories of women and people of color were overlooked, since the goal was to capture all the older voices in the industry before they were gone. In recent years, we have tried to interview more of the people whose names and stories may have been overshadowed by someone more well known or who was more accessible due to their stature in the industry. We have tried to interview more below-the-line individuals in the same way.

The Interviews preservation effort is well underway! We have digitized many of the earliest and more recent tapes at the University of Southern California Digital Repository. The technology and techniques available today are far superior to the past, and the quality of picture and sound that USC is able to capture and preserve is impressive.

We are also completely revising our internal cataloguing thesauri and process to expand the vocabulary to include more inclusive and updated terminology.

We have several other means of outreach for this collection, such as the Google Arts & Culture Exhibits https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/archive-of-american-television and our Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/FoundationInterviews/. Through feedback and Google Analytics, we have a good idea of our user base: academic researchers, academic professors, television aficionados and filmmakers.

I hope to continue to help shepherd The Interviews into the next 25 years and do my part to ensure these stories are accessible to future generations. We are working on expanding user access to this collection and creating classroom curriculum in partnership with Nancy Robinson and the Foundation's Education Programs department to reach more students and faculty. We are also exploring ways to make the collection more accessible through closed-captioning and translations into other languages.

On the occasion of The Interviews' 25th anniversary, I am very proud and humbled to have been a part of this historic collection.

Read more about The Interviews 25th Anniversary celebration, held December 6, 2022, here.