It was a crisis no one had foreseen, and no one was prepared for. Doctors and nurses did their best to keep people alive, but the hospital staff was overwhelmed. As suffering intensified, fatigue gave way to frustration, confusion and anger. Where was the help? Why wasn't the government moving faster, doing more to help its citizens?

Sound like 2020? This was actually 2005, inside Memorial Medical Center in New Orleans during the five hellish days after Hurricane Katrina made landfall on August 29. Later it would be known that the Category 5 storm caused more than 1,800 fatalities and $125 billion in damage. And it would also be revealed that the doctors and patients trapped in Memorial — surrounded by filthy storm water — lacked power, clean water, food and medical supplies. Temperatures indoors reached 110 degrees.

Mortuary workers eventually carried forty-five bodies out of Memorial (now known as Oschner Baptist Medical Center), but this was no ordinary tragedy set in motion by a natural disaster. Some of the dead, it was later documented, had been injected with lethal doses of morphine and the sedative midazolam in what some have called mercy killings. This incredible story — told in a Pulitzer Prize–winning investigative piece by Sheri Fink for the New York Times Magazine in 2009 and in her 2013 nonfiction book, Five Days at Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital — informs Apple TV+'s Five Days at Memorial, premiering August 12.

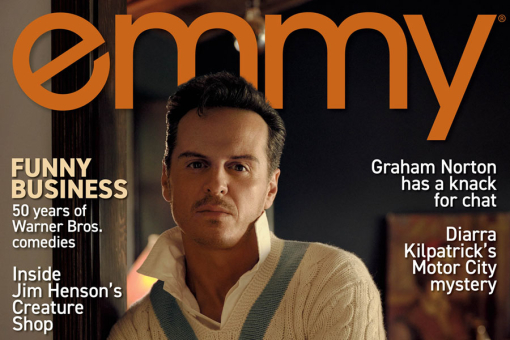

Sheri Fink "managed to tell a very intimate story, but one that has great levels of resonance beyond just what happened in that hospital," says Carlton Cuse, the Emmy-winning producer (Lost) who teamed with Oscar-winning writer John Ridley (12 Years a Slave) for the eight-episode limited series. "She did such a good job of addressing some big issues of medical ethics. I felt so passionate about the story," which he describes as "incredibly well-researched... and it was a story that I really wanted to tell."

With Cuse and Ridley as executive producers and coshowrunners, a cast of stellar performers signed on to portray the medical professionals who endured those dark days. Vera Farmiga (When They See Us, Bates Motel) plays the story's most controversial figure, Dr. Anna Pou, who in 2006 was arrested, along with two nurses, in connection with the deaths of four elderly patients. The state alleged that the patients had been euthanized shortly before the hospital was evacuated. But the following year, a New Orleans grand jury declined to indict Pou or the nurses on the charge of second-degree murder.

Five Days depicts in compassionate detail the emotional and psychological state of Pou, a respected head-and-neck surgeon, and the entire team as they made choices that would follow them for years to come.

"What happened," Ridley tells emmy via email, "was an example of systemic failure, and understanding flawed and biased systems requires complicated examinations."

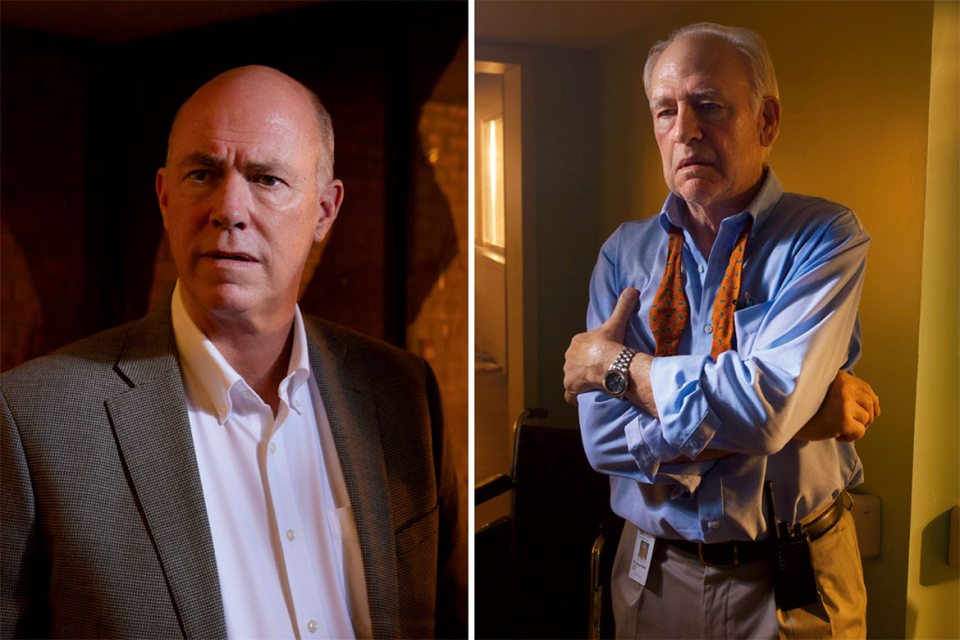

Also recruited for this complex tale were three-time Emmy winner Cherry Jones (Succession) to play Susan Mulderick, the nursing director and head of the hospital's emergency- preparedness committee; Robert Pine (Magnum, P.I.) as Dr. Horace Baltz, one of the longest-serving physicians at Memorial; Cornelius Smith Jr. (Scandal) as Dr. Bryant King, an internist new to the facility and one of its few Black physicians; and Adepero Oduye (When They See Us) as I.C.U. nurse manager Karen Wynn, who led the hospital's ethics committee. Another standout: Michael Gaston (The Leftovers) as assistant attorney general Arthur "Butch" Schafer, whose investigation helped unravel the tragic events.

Five Days offers much to unpack. As the staff realizes no help is forthcoming, wrenching choices develop. Did a patient who previously declined to be resuscitated also waive the right to be saved in an emergency? For someone in great pain — with little to no chance of survival and even less chance of evacuation — would a lethal dose of drugs be considered compassionate care or homicide?

These are impossible choices, fit for debate in classrooms and seminars. But these professionals were not at a conference — they didn't even have drinking water. Five Days yanks the viewer out of the comfortable seat of judgment and asks many tough questions, among them: What would I have done?

"I can't even begin to measure what I would do or how I would feel unless I was in that very circumstance," Farmiga says. In preparing for the role, she had no contact with Dr. Pou, who has maintained that she had not intended to euthanize patients but rather to provide them with comfort in unthinkable circumstances. Farmiga allows that it was a challenge to play someone she'd never met, but "most of the preparation was to just grasp the abysmal conditions of the hospital that were zapping everyone's mental and emotional reserves."

Five Days has itself risen from the dead at least twice. Producer Scott Rudin originally optioned Fink's book, with plans to turn it into a feature film. After the option lapsed, producer Ryan Murphy acquired the rights, intending to use the book as source material for American Crime Story: Katrina, with Sarah Paulson attached to play Dr. Pou. When that project was shelved, Cuse stepped in, confident he could bring the project to fruition under his overall deal at ABC Signature.

"I saw that if Scott Rudin and Ryan Murphy couldn't get it made, it was probably going to be a big challenge," Cuse recalls. "I realized that the degree of difficulty was very high, but I was willing to do whatever it took."

Cuse says his "first, best and most important decision" was to ask Ridley to collaborate; Ridley says he was equally excited to work with Cuse. "While there were any number of reasons to take on the project," Ridley explains, "for me, the differentiator was the opportunity to work with Carlton. Even with all his years of experience and his crazy level of accomplishment, he was collaborative beyond the necessary. The project wouldn't exist, this story would not have been told if it weren't for Carlton."

But how that story was ultimately told required resources rivaling a summer blockbuster. Part disaster flick, part tragedy, part mystery, part Southern Gothic thriller, Five Days blends CGI magic and engineering wizardry to create a hellish spectacle. Water becomes a villain, disintegrating homes and washing cars away; many scenes feature actors wading through pools of murky, waist-high reservoirs to create an eerie post-apocalyptic feel.

Shot in Toronto and New Orleans during spring and summer 2021, Five Days used a 5 million gallon water tank and a facade of the hospital made to scale.

"Our production design team had access to photographs of the hospital in the aftermath of Katrina," Cuse says. "We tried with painstaking detail to replicate what it looked like inside. Achieving a sense of authenticity was a high priority."

The meticulously created surroundings — along with the assured direction of Ridley, Cuse and Wendey Stanzler (Ridley and Stanzler each helmed three episodes and Cuse handled two) — convey how dire the circumstances were.

For example: "Ridley would remind us not to use deep, slow breathing, but short, shallow breaths," Jones recounts, "because there was no oxygen."

As the storm hits, lights flicker, windows shatter, walls collapse. By the next morning, the storm has passed and the hospital staff is relieved. But then days tick by without rescue, and they must live with the heat, stench and growing desperation.

"We were drenched all the time," says Cherry Jones, explaining that actors were slathered with Vaseline and sprayed with water to mimic sweat. "It was so important to portray the physical deprivation, because the stress their bodies were under affected their choices. John was particularly strong in that department," she says of Ridley. And of Cuse and Ridley, she adds: "I've never in my life worked with two greater gentlemen. We felt so safe on that set, and it was a complicated set for a lot of reasons."

Behind the scenes, Jones says, all the actors — who were sequestered during filming due to Covid protocols — formed a supportive community. And as they processed the trauma they were re-creating, they resorted at times to dark humor.

On weekends, Jones says, the principals would gather to talk. "We inevitably would start to debate whether what happened was right or wrong. And it broke down [along these lines]: if you played a character who had been involved with the choices at the end, you agreed with them. If your character did not agree, the actor did not agree. It was remarkable. I've never been in an experience like it."

Images of Katrina and its aftermath will likely be forever seared into our collective memory: residents on their rooftops, waving at helicopters; masses packed into the Louisiana Superdome like refugees in their own hometown; that jaw-dropping moment during NBC's A Concert for Hurricane Relief when Kanye West went off-script saying, "George Bush doesn't care about Black people." Whether one agreed with the sentiment or not, the statement brought to light what many felt was left unsaid in conversations about the handling of the disaster: race played a part in the botched response.

For some, that's the singular, standout takeaway to this day, the thesis that eclipses everything else. But Five Days handles race and even class subtly, neither making them prominent themes, nor ignoring them.

Smith's character, Dr. Bryant King, provides the perspective of a Black doctor — the sole Black physician among those depicted. And though Five Days presents the care and concern of the entire Memorial staff for its patients, King serves as a moral center, a doctor who feels the suffering of patients — many of them Black — more deeply than his white colleagues.

"Race is a character in itself," Smith says. "On some level, either consciously or subconsciously, it had an effect [on patient care]. For my character, it greatly affects how he moved through that space." As rumors spread around Memorial that euthanasia is being discussed, Smith delivers this chilling line: "Who you think they're going to start with?"

Meanwhile, outside the hospital, desperate residents — mostly Black — wade through the fetid pond that New Orleans had become to reach Memorial, hoping for aid for themselves or loved ones. King watches in despair as they're turned away, sometimes by force.

And back inside, rumors swirled that "people" on the outside — implied to be Black people — were looting, raping or worse. King reminds those repeating unsubstantiated rumors of the humanity of the people in crisis.

"That moment... it kind of shook him," Smith says of his character. "Because anybody would normally say, 'Stealing, that's wrong.' And of course, Black kids were doing [some of the looting]. But when you look at it from a survival standpoint, people were just doing what they had to do to provide for their families. [King] found himself having to look out not only for himself, but for the African-American patients in there. That's a lot to take on. It's very real, and it's very heavy."

So much in Five Days triggers introspection and soul-searching, but in watching the horror from the not-too-distant past, echoes of the more recent pandemic years are impossible to miss. Cuse says his goal in telling this story was to remind people of what happened in New Orleans — and to think about what could happen next.

"I hope that we, as a society, can get to a place where we don't put healthcare workers in the position that they were put in, having to make the decisions that they had to make. The pandemic was different than Katrina, but it put healthcare workers in some of the same circumstances, forcing them to make difficult choices. I hope we'll learn how to be better prepared for the next crisis that comes down the line. And there will be one."

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #8, 2022, under the title, "Hell in High Water."