Prolific writer-producer David E. Kelley has been a creative force in television for more than 35 years. He dominated the television scene in the ’90s, becoming a household name as creator of the series Picket Fences, Chicago Hope, The Practice and Ally McBeal. He capped off the decade with a bang in 1999, winning the Emmy Award for Outstanding Comedy (Ally McBeal) and Outstanding Drama (The Practice) in the same year, a feat no other producer has accomplished.

Born in Waterville, Maine, Kelley graduated from Princeton University and earned a law degree from Boston University School of Law. He practiced law in Boston for three years before venturing into the world of entertainment, when he was brought on as a writer on L.A. Law. He credits that show's cocreator Steven Bochco, who died in 2018, with launching his television career. "I couldn't have asked for a better mentor to have, or a better introduction to the process," he says.

Known for writing first drafts by hand on a yellow legal pad, Kelley has been nominated for thirty Emmys and has won eleven. His most recent win was in 2017 as executive producer of HBO's Big Little Lies, which was named Outstanding Limited Series. He has been married to actress Michelle Pfeiffer since 1993 and was inducted into the Television Academy Hall of Fame in 2014. Most recently, he created Love & Death, Max's most watched original limited series globally in 2023. In 2024, Kelley is set to premiere two limited series: A Man in Full for Netflix and an updating of the Scott Turow bestseller, Presumed Innocent, for Apple TV+.

Kelley was interviewed in March 2014 by Amy Harrington for The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be screened here.

Television Academy: What did you want to be when you grew up?

David E. Kelley: When I was very little, I wanted to be a professional hockey player. By the time I got to high school I knew the chances of that were probably remote. When I was in college, I started to gravitate toward the law. I don't think I truly knew what I wanted to be until I came to California and sat for my very first meeting in a writers' room with Steven Bochco and the writers of L.A. Law. It was at that moment that I said to myself, "Oh, this is what I'm meant to do."

What attracted you to the law?

It's society's best effort to legislate moral and social behavior. It is very imperfect; it is very inexact. It's fodder for a tremendous amount of debate — people tend to expose their values and character in the process of that debate. I always found that a joy to participate in, both as a student and as a layperson talking about the law. When I subsequently became a writer, I experienced the same joy — mining characters through their values systems and beliefs, the tightrope between what's right and what's wrong. Most of my shows have been character-based, but I've used the law as a springboard in a lot of those shows to really mine those characters.

When did you start writing?

While I was a lawyer. I liked to write in college; it's not something I ever considered would be a career. The thing you go to law school for, to stand up in front of a jury and deliver arguments, you're not tossed into as a young litigator in great abundance. I was frustrated by that, and I got an idea: What would a frustrated young litigator do to manufacture a big case for himself so he could jumpstart his career? I started writing this screenplay, From the Hip, about this young, ambitious, fictional lawyer.

I did manage to sell that screenplay, and the timing was fortuitous; there was a gentleman named Steven Bochco developing a law show called L.A. Law. My script made its way to him. He was looking for lawyers/writers so it could feel authentic. I came out to meet with him and ostensibly do an episode, and as soon as I met him, from the first meeting I knew that I probably would not be practicing law anymore. I came to join them for the first season and took a leave of absence from my law firm. L.A. Law became a hit, and I got a call from my law firm saying, "You're not going to come back, are you?" I said, "Probably not," and here I stayed.

Talk a little bit about Bochco.

I couldn't have asked for a better mentor to have, or a better introduction to the process of television. Steven Bochco demands excellence. He does not write down to the audience. He will dare the audience to rise up and follow a complicated plot. He always respected the audience, and he taught us as writers to do the same. And he was also the most gifted and prolific producer of our time. He was a really great teacher. Steven was a wonderful communicator, and if you got a chance to work with him or for him, it's a very lucky break. It's probably the luckiest break I got.

What's the most important thing you learned from him?

Take care of the scripts. Don't settle for "It's pretty good." If you can make it better, make it better. Steven was very good at establishing that mindset on L.A. Law and with all his shows, and that's something I've done with mine.

What position were you hired for when you started?

I was hired as a story editor/staff writer and became a co-producer in year two.

Ultimately what role did you have on the show?

By the end of year three, I was in charge, which was ridiculous. I had only been in the business for three years, and Steven was going to go do Cop Rock and said, "Here are the keys to the car. Don't crash it."

And did you learn to drive?

I learned to drive because I had a tremendous support system. The producing and writing were very, very strong, the teams were already in place, so my primary job that first year as showrunner was taking care of the scripts. I felt pretty good on that level. And I had no problem asking people to hold my hand. I needed to learn so many of the producing skills in order to make the television show, and Steven was here on the lot, so I had a ton of help.

Why did you leave L.A. Law?

I had been there five years, and that seemed like a very long time for a young writer on one show. I loved the job, but I was at a hundred episodes, and at some point you have to tell other stories, write about different characters. The timing just seemed right. CBS was interested in making a deal with me to develop shows for them.

In 1992 you created, wrote and executive-produced Picket Fences. How did that come about?

I had several meetings with [president of CBS Entertainment] Jeff Sagansky. He would throw out what they were looking for, and I would throw out what I was looking to write, and we found a middle ground. They responded to the idea of a small town with a cadre of characters in a more rural setting, because Northern Exposure was working for them. I wanted to take a plot line and play it through several different prisms: through the police arena, the legal arena, the township at large and then ultimately through the nuclear family. The tone was offbeat. It had dark comedy to it, but it also had straight dramatic storytelling as well.

It was a juxtaposition of different tones. We would allow our audience to laugh at a situation, but we would not want them to then trivialize the underlying dramatic point that was causing them to laugh. That was tricky. We did a lot of reshooting on Picket Fences because the tone was very, very tricky.

In 1993 and again in '94, that show won the Emmy for Outstanding Drama Series, as well as a slew of others. What did that honor mean to you?

It actually meant a lot. In addition to being a great honor to win an Emmy Award, it was a lifeline to survival. We were not a hit show. The irony is that, by today's standards, we'd be a juggernaut. I think we had a 20-something share or 12-something rating — it'd probably be a number one dramatic show by today's standards. But at that time, with only three networks, that was not quite enough. We were hanging on. We needed to get more viewers in order to survive. As a result of us winning an Emmy, I think we got more eyeballs tuning in, so it meant a great deal. It was great validation to a company of people that really believed in the show and loved doing the show, and it was a rewarding and fun night.

While Picket Fences was on the air you also created Chicago Hope.

Yes, CBS came to me and said, "Would you be interested in doing a medical show?" The idea was intriguing; it was something new for me. One of the shows that I watched before I entered the world of television was St. Elsewhere. I loved that show. So I started meeting with some doctors, touring some ORs and thought, "I'll give this a try," and ended up writing a script. CBS liked it and wanted to produce it. It was a little fast for me because we were doing Picket Fences, which was a difficult show to do. I knew going into Chicago Hope I would have to find other people to come in and take over the day-to-day showrunning responsibilities. I wrote and produced the first year of Chicago Hope and then turned it over after the second year.

Then in 1997 you created The Practice.

Yeah, I pitched it to ABC almost as the opposite of L.A. Law. With L.A. Law, you took these big cases and these lawyers live glamorized lives. [The Practice was] going to be about the nuance of practicing law. You would see lawyers struggling to pay their rent, struggling to collect fees from clients. It was going to be a much more microscopic look at the inner workings of a law firm. That’s how it was conceived and how the pilot was written. Then we didn’t make the schedule. My contract allowed for the show to revert back to me. There were marching orders at ABC that under no circumstances do we want any show that we develop to go be a big hit on another network. ABC didn’t want to put it on their network, or have it go to another network, so they decided to put it on Thursday night against ER, where the show would likely be tarnished, and no other network would want it. We actually never aired on Thursday night; it got pushed to Saturday night at ten, the real death. We did limp along and survived on Saturday night, and then ultimately did become a hit on ABC.

But it changed the construct of the series when we got moved to Saturday. I knew a show about the microscopic inner workings of a law firm was never going to fly on Saturday night at ten. So we completely changed our form of storytelling: The cases became grander, the stories became more provocative and button-pushing. It was all shaped by a fateful horrific time slot that we got. By kicking us to the graveyard, ABC may have given us a boost we couldn’t conceive of at the time.

In the final season, there were some significant changes to the cast and the show. Why were those changes made?

I got a call: “Would you be willing to come back one more year, basically at half-price?” I had about five minutes to think about it, because it was the Sunday before upfronts. On the one hand, I didn’t want to do a subset of the show, but on the other hand, it felt wrong the way we were limping out, and I wanted to go out on a higher note. That sentiment won out, so I said, “Sure, we’re going to go for it.” The cost-cutting logistics necessitated that I lose half the cast. Also, we had some creative issues. The upside for that as storytellers is now you can go for broke that last year. That occasioned us to write the character of Alan Shore, played by James Spader. The show caught on creatively again, so much so that ABC came back and said, “You have your choice: We’ll do another year of The Practice, or you can do a spinoff with this character Alan Shore and Denny Crane," who was played by William Shatner. When we sat down to write scripts, Alan Shore and Denny Crane were at the fore, so that was a clear indication to me that there should be a spinoff.

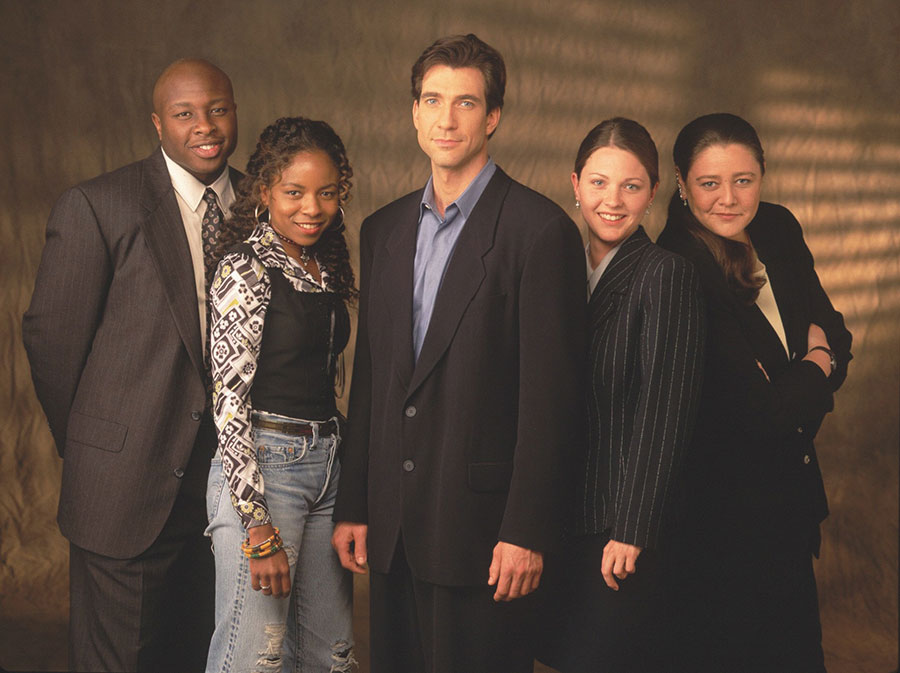

Dylan McDermott and the cast of The Practice

It feels like Boston Legal had a stronger point of view on the issues than The Practice. Why was that?

I was never interested in getting on a soapbox and taking a stand on an issue. If you look at Picket Fences and The Practice, if an issue didn't have two strong sides, I wasn't interested. The greatest compliment that we could hear is that people were fighting in their living rooms, arguing amongst themselves while watching the show about what was the right position. When Boston Legal came into being, it was the post-9/11 era. Dissent became an evil word. Debate was now this horrible thing to do. It became politically incorrect to ask hard questions of your leaders, of your country. With that, Boston Legal became a bit of a town crier. I always felt it was irresponsible for a producer to use a television series as their podium. But when I saw everyone going the other way, being afraid to tackle issues and being scared to ask tough questions, I looked through a completely different prism — maybe it's irresponsible for us not to use our podium on occasion. Maybe there's room on the television landscape for one show to jump up and down and say "this isn't right" on a given issue. We let the characters do that, but we tried to tuck it under entertainment. I always said, "Do not preach, entertain." But the dirty little secret on Boston Legal is we would entertain, entertain, entertain and then preach like hell in that fourth act.

Backtracking a little, while you had The Practice on the air, you created Ally McBeal, also a legal show, but with a very different tone.

Right. Ally McBeal started off as a romantic comedy. I'd never done one before. Ultimately, I came back to the law office setting, probably because I was comfortable with it. But this show, by its conceit, was really going to mine the moral and ethical and romantic inner workings of characters. Law would be a great springboard to do that, because the law is always challenging us, how we feel, how we think. Law was just the backdrop where this cauldron of characters came to interact. It was very single-lead-oriented in its original draft, and I really wanted to focus on the dichotomy of this one character — her inner life and her external life. It was not going to be set up on straight linear or dramatic tent poles, so the architecture of the series was going to be different.

There was something very distinct about the visual fantasies. How did you develop that?

I had never really attacked scripts filmically, and I thought this would be something new, to actually see what you're hearing or feeling as opposed to saying it. That gave rise to the fantasies, and the fantasies were a great luxury, because they didn't have to bear any connection to reality. They could be an exaggeration of a feeling and were great fun and very entertaining.

Where did the dancing baby come from?

My assistant came in and said, "You've got to see this crazy dancing baby." She [found it online] somewhere. I was both riveted by it and scared of it at the same time. I knew I had to have it, that it could be the manifestation of Ally's biological clock. She's excited that maybe she wants to have a baby, but at the same time it's the most frightening thing known to mankind. That's the perfect fantasy for that, so we reached out to the person who had designed it and they said yes, and the dancing baby became part of the show.

What advice would you give to someone starting out who wants to be a television writer or producer?

I would say write what's in your heart, what you want to write, not what you think others will want to see. Once you start guessing at other people's tastes, you start subjugating your own instincts to the visions of others. You'll end up being lost. Doesn't mean that what you want to write and what you love will always be successful, but you have a greater chance of achieving success if you stick to what's in your heart and mind.

The contributing editor for Foundation Interviews is Adrienne Faillace.

Since 1997, the Television Academy Foundation has conducted over 900 one-of-a-kind, longform interviews with industry pioneers and changemakers across multiple professions. The Foundation invites you to make a gift to the Interviews Preservation Fund to help preserve this invaluable resource for generations to come. To learn more, please contact Amani Roland, chief advancement officer, at roland@televisionacademy.com or (818) 754-2829.

Click here to see more interviews.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #12, 2023.