In 1972, CBS and 20th Century Fox Television had modest expectations for a new comedy series about drafted surgeons saving the lives of wounded soldiers in the Korean War, which had ended some twenty years earlier. Indeed, after its first season, the future of M*A*S*H was in doubt. But CBS and Fox were proven wrong. TV's first dramedy ran for eleven seasons — from September 1972 to February 1983 — and along the way picked up fourteen Emmys and a Peabody Award.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the series premiere. The historic, two-and-a-half-hour final episode, which ran on February 28, 1983, was the most-watched TV broadcast to date. "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen" drew 105.9 million viewers, earning an unheard-of 60.3 rating and 77 share. (By comparison, the current record holder for most-watched program of all time, Super Bowl XLIX, had 114.4 million viewers.)

This groundbreaking series about the 4077th MASH (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital) was based on Robert Altman's hit 1970 feature, M*A*S*H. That movie was in turn based on 1968's MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors, written by former MASH physician H. Richard Hornberger (with help from author W.C. Heinz) under the pen name Richard Hooker.

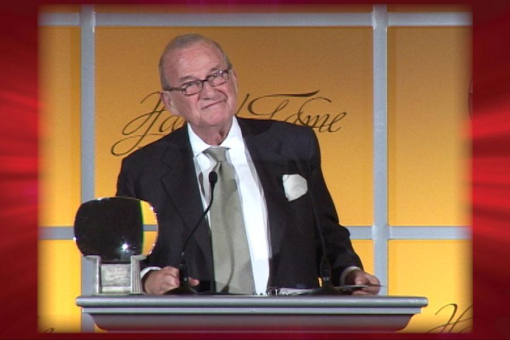

Created by comedy writer Larry Gelbart and writer-producer Gene Reynolds, the TV series was widely believed to have been inspired by the Vietnam War, which was still raging for the first three years of the show's run. After Gelbart and Reynolds departed for other projects (four and five years in, respectively), associate producer Burt Metcalfe became executive producer for the rest of the run.

M*A*S*H owed much of its popularity to its family of quirky military characters. Alan Alda played a smart-alecky, skirt-chasing surgeon (Captain Benjamin Franklin "Hawkeye" Pierce); Loretta Swit was a highly principled but lusty head nurse (Major Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan); Gary Burghoff portrayed a company clerk with super-acute hearing (Corporal Walter "Radar" O'Reilly); Jamie Farr played Corporal Maxwell Q. Klinger, who wore women's clothing in hopes of getting discharged as psychologically unfit; and William Christopher served as First Lieutenant Father John Mulcahy, the company priest, whose church was in the mess tent.

Ace writers created compelling stories, many based on real-life experiences of real MASH doctors. Mixing comedy and drama within each episode, they depicted the horrors of war in operating-room scenes laced with tension-releasing humor. The surgeons lived in a messy mancave of a tent dubbed the Swamp, where they drank martinis made possible by Hawkeye's still, part of the decor.

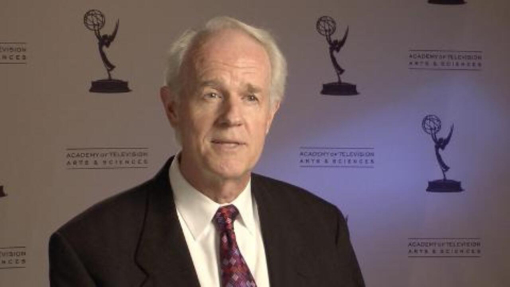

M*A*S*H was notable for a number of cast changes. For example, Gary Burghoff, the only principal actor from the feature who'd segued to the series, left the show in 1979. Other significant changes: McLean Stevenson (Lieutenant Colonel Henry Blake) was replaced by Harry Morgan (Colonel Sherman T. Potter, a new character); Wayne Rogers (Captain "Trapper" John McIntyre) was replaced by Mike Farrell (Captain B.J. Hunnicutt, also new); and Larry Linville (Major Frank Burns) was replaced by David Ogden Stiers (Major Charles Winchester, another new character).

A spinoff, AfterMASH, launched in 1983 with just three characters from the original series — Klinger, Mulcahy and Potter — but it lasted only two seasons.

Today, the original M*A*S*H can be seen night and day on MeTV and TV Land and streaming on Apple TV+, Hulu and Prime Video.

In recent years, several of the show's principals have passed away: producers Gelbart and Reynolds as well as actors Christopher, Linville, Morgan, Rogers, Stevenson and Stiers. To mark the show's milestone anniversary, emmy contributor Jane Wollman Rusoff spoke to members of the main cast, as well as Metcalfe and other writers and producers. Their recollections of the landmark series have been edited for length and clarity.

TUG OF WAR

John Rappaport (writer-producer): M*A*S*H got on the air despite everything: CBS didn't like it. But nobody had wanted to publish the book, either. And the movie that supposedly nobody wanted to see turned out to be a hit.

Alan Alda (actor-writer-director): They gave us a small stage because they didn't think we were going to be successful. We didn't have our own bathroom for six years!

Jeff Maxwell (actor, portrayed Private Igor Straminsky): After the first year, the scuttlebutt was that the show was vulnerable to being canceled. Larry Gelbart and Gene Reynolds went to bat for it hard.

Ken Levine (writer): It was in a terrible time slot — Sunday night. But Babe Paley, the wife of CBS CEO Bill Paley, absolutely loved the show, and that went a long way to getting it renewed.

Jamie Farr (actor-director): There were sixty-five [primetime] shows on at that time, and M*A*S*H was number fifty-seven. Bill Paley moved it to Saturday night. At the beginning, M*A*S*H didn't have a formula, but they soon found it: there was a serious reason for those guys and gals being there — but remaining there drives you a little nuts.

Elias Davis (writer): Gene wanted to make the show less strictly comedic and add an element of reality. So Larry came up with the idea of a journalist friend of Hawkeye coming through the MASH unit to do a story ["Sometimes You Hear the Bullet"]. He gets seriously injured. Hawkeye has to do the surgery, which fails and the guy dies. That [season-one] episode turned the show around and made the series: you could do serious and comedic stories in the same episode.

Levine: The theme of the show was an existential dilemma: drafted doctors who are forced to be in the war zone, trying to save lives [in a place] where the goal was to kill as many people as possible.

Gary Burghoff (actor): Early on, we were given scripts that were fluff — situation comedy-type. We went to Gene and Larry: "We're not a situation comedy. We're talking about a real war. It's not about funny ha-ha."

Levine: There were people who didn't like the show and thought we were liberal communists. We'd get some delightful letters.

Dan Wilcox (writer-producer): A lot of people felt that M*A*S*H was really about the Vietnam War. Later, I was at a party of M*A*S*H alums. Larry Gelbart, Gene Reynolds, Burt Metcalfe and a couple of others all agreed that the show was never intended to be about the Vietnam War. I came away positive that it was about Vietnam since they didn't want to say so.

Alda: The Vietnam War was being fought and heatedly debated when M*A*S*H began its run, so many people felt the show referred to that war in particular. As far as I was concerned, M*A*S*H was specifically about the Korean War but, in a way, stood in for all wars.

LARRY GELBART AND GENE REYNOLDS

Alda: Larry was a delicious meal. He was supportive, good-natured and had such a brilliant comedy mind.

Loretta Swit (actress): In the second season, I was starting to feel that it wasn't going to work if my character didn't evolve. Larry was an ally. He'd say, "Hang in there; we're going to find her."

Alda: The show wouldn't have been what it was without Gene Reynolds. He was a wonderful director, a terrific storyteller. Even after we began shooting, he was taking a course in short-story writing to get a better sense of storytelling.

David Isaacs (writer): After Gene left, we'd still meet with him every Thursday night at his house to go over story work.

Burt Metcalfe (executive producer–director): Larry was a comedic genius, and we knew we could never make the show as funny as he had. That wasn't my biggest strength, and it wasn't Alan Alda's either, in terms of writing. So we knew we had to develop the characters more, to plumb the depths of those people and their relationships with one another. We began doing stories much more about their lives. Critics thought the show had become pretty serious and that it wasn't as funny as it used to be. They started calling it a dramedy, which we didn't see as an insult.

Alda: It's a myth that when Larry and Gene left, I [gained more control]. I didn't get any more control. I didn't ask for any more. I didn't have any. Burt Metcalfe was the producer in charge of everything.

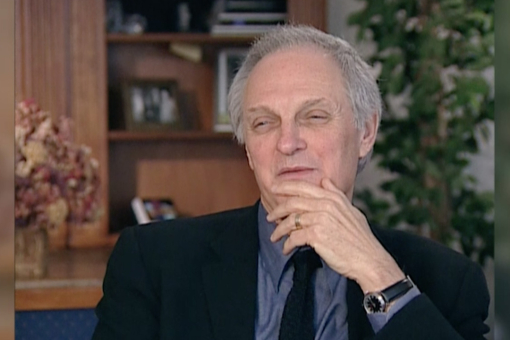

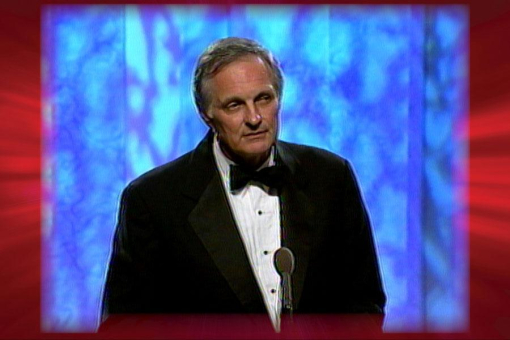

ALAN ALDA

Alda: I was in the Utah State Prison making a movie [The Glass House] when Gene offered me the part. I wanted to do it, but I needed to make sure that it wasn't going to be high jinks at the front or like McHale's Navy or other service comedies set during a war that ignored the war. They agreed.

We rehearsed the pilot for about ten days, but I still didn't feel I knew who Hawkeye was. I didn't feel I was putting on the shoes of this character. Then I started wearing some army boots that an army vet had actually worn. I put on dog tags that had belonged to real soldiers. When the director called "Action!" I was still thinking, "How do I be this guy?" I opened the door. I walked across the compound. A nurse was coming toward me. I grabbed her around the waist and said, "Hello!" All of a sudden, I thought, "It's not so hard to be this guy!"

When I wrote episodes, I didn't ignore Hawkeye's character trait of pursuing women, but I tried to explore their stories as people, not just as colliding sex objects. Other writers may have dealt with this by avoiding the subject altogether. But we got some good stories when women were written as having the same need for respect as men.

Burghoff: Alan was the Commander in Chief of Integrity. There were certain powers that were counterproductive to our becoming a show about pro-humanity rather than a "ha-ha" sitcom. The cast would express their fears, and he would speak for us. The people in power listened.

Metcalfe: The characters of Margaret and Hawkeye changed. In the two-parter when they thought they were going to be bombed and die ["Comrades in Arms," season six], they had sex."

Mike Farrell (actor-writer-director): A big part of the show was drinking. The Swamp [the doctors' tent] was where we supposedly made martinis in our still.

Rappaport: Alan is a great writer. He's also a fabulous eater. When you work with him, you go out to lunch and dinner, no matter what. He loved Chinese food. There was a full refrigerator at his house, always. We either wrote at a restaurant or in his house.

LORETTA SWIT

Swit: I knew I was never going to play my character the way that nickname, Hot Lips, would indicate. She was a head nurse and more than just one piece of her anatomy. By about year three, her name in the script was Margaret — it no longer said Hot Lips. She had become her own person, grabbed hold of her authority and used it well.

Metcalfe: When casting the pilot, I saw a TV show that Loretta had done. She was attractive. She was strong. She had a lot of ability to play the conflict and be serious and somewhat of an obstacle for the mischief-makers.

Swit: What really shot [my character's evolution] forward was a momentous conference call I had with Gene, Larry and the writers. They opened with: "Where do you see Margaret going? We can start developing it." I said, "Send me to Tokyo. Let me meet somebody who outranks Frank. Let me fall in love. I'll bring him back and I'll be engaged."

So we went forward. Margaret got married but her husband, Lieutenant Colonel Donald Penobscott, later betrayed her and we wound up getting a divorce.

Farrell: Loretta used to do needlepoint on the set. I always loved that she'd be very daintily making something beautiful — then they'd call her and she'd rush to the set and start screaming at Hawkeye or someone.

WAYNE ROGERS

Wayne Rogers (actor): I was having a beef with the studio and was thinking of leaving.... The show was going into the third season, and I still didn't have a signed contract. Among other problems, Fox had refused to remove the morals clause it added after we made the initial deal.... People always ask if I regret leaving. No, [I don't]. I went into business almost immediately after I left.

[Rogers left the show in 1975. These comments are excerpted from his 2011 book, Make Your Own Rules: A Renegade Guide to Unconventional Success.]

Alda: Wayne would have stayed if he wasn't constantly being called on to just sit in the scene and say practically nothing. I think that finally got to him.

Metcalfe: When Wayne got the part, it was our intention to have him be fairly equal with Alan. But Alan, by sheer weight of his character, kind of took over.

MIKE FARRELL

Farrell: Alan and I would play chess and Scrabble in a shed that became our little hideout. We had push-up contests. I kept saying, "Alan, you're going to lose." More often than not, he did. He used to crow when he beat me at something.

GARY BURGHOFF

Alda: Gary was immersed in playing a scene truthfully and beautifully. He'd spend a lot of time just working out a little piece of business.

Swit: Gary and I were together from hello. It was magic.

Allan Katz (writer-producer): Gary was eccentric. In one episode, he was to bring breakfast to [newlyweds], but they didn't want to be bothered. The script [called for] him to eat the breakfast himself. He wanted to know why he would eat somebody else's breakfast. So we had to give him an actor's reason.

Burghoff: I believe that God spoke through Radar, as well as through the other characters. [Compared to how I played him in the film], I worked to make Radar a more innocent, naïve person to counteract the more sophisticated characters around him.

The M*A*S*H book said that Radar had ESP. You can't act ESP. So I chose to physically manifest it by adding a pair of glasses: Radar had acute hearing to compensate for not being able to see well. He could always hear the helicopters coming [carrying the wounded] before anybody else. He was listening for them. That was his job. It was Larry Gelbart's idea for Radar to have a teddy bear. I did it for a one-time thing, and then begged Larry to keep it in.

By the time I left, my career had become my life. I wanted to spend more time with my family on the East Coast in the countrified environment that I grew up in. So when my seven-year contract was up, I decided not to renegotiate. I didn't stomp my feet and walk off the set. I fulfilled my contract and was very deeply honored to have been there.

JAMIE FARR

Metcalfe: We always wanted to make it very clear that Jamie's character, Klinger, wasn't gay. He was just trying to get out of the service.

Farr: They got my costumes from the Fox wardrobe department. The guy would say, "Alice Faye wore this" or "Betty Grable wore that." He picked out a gold lamé that Ginger Rogers had worn, and Nurse Kellye [Kellye Nakahara] and I did a takeoff on Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

Alda: Klinger started out as one sight gag. But over the years, he developed recognizable characteristics. He went from wearing fashionable ballgowns to just the flair of a kerchief, because he had become a character beyond the sight gag.

WILLIAM CHRISTOPHER

Alda: He astonished everybody because not only was he was a fine actor, but a Greek scholar. You'd keep track of what month it was by looking at how far he'd gotten in reading The Iliad in the original.

McLEAN STEVENSON

Burghoff: McLean had this off-the-wall sense of humor that completely broke the tension — and we were under great tension the first two seasons, especially the first. McLean was always there when you were most worried about the next scene. There he was, with a little makeshift stand made of orange crates, selling tickets to watch his cousin eat a goat.

Katz: McLean left because he thought he would have a career hosting his version of The Johnny Carson Show. He had guest-hosted. But he didn't get a talk show.

HARRY MORGAN

Swit: Everybody would walk all over Henry Blake. But when Colonel Potter came in, there was a very different guy in command. Potter was a thirty-year army man, totally devoted to the army and his family.

Katz: One night, we were running about an hour late. Harry said, "Excuse me, I've got to make a phone call." When he came back, we asked if there was a problem. He said, "No, no. I have a monthly poker game and just wanted to let people know I'd be late." We squeezed out of him that he played with Henry Fonda, Jimmy Cagney, Jimmy Stewart — all these Hollywood legends.

LARRY LINVILLE

Metcalfe: Larry's character, Frank Burns, was a paper tiger — he'd threaten, but he didn't have the macho to worry anybody.

Swit: They wouldn't let Frank be a good doctor. They called him bad names like "lipless wonder" and "ferret face." The love scenes with me were clumsy. He was married. Margaret had no respect for him. Why was she with him? Larry walked into a tent and was funny even before he said anything. But playing that character didn't give him a chance to expand and show the kind of actor he was. There was a point when he stopped going to the dailies. He said, "I just can't watch myself play Frank anymore."

Burghoff: Larry was so clever that he actually built a real airplane in his apartment in Los Angeles, then took all the pieces to the desert, put it together and flew it.

Isaacs: Hot Lips and Frank represented the establishment. As the years went by, Frank never grew, but Hot Lips transitioned into Margaret, at a time when women were becoming an important part of the working world.

DAVID OGDEN STIERS

Metcalfe: David's Major Winchester was stronger [than Burns]. He was an authority figure and better opposition.

Wilcox: David's character felt superior to everyone. He was a better surgeon than the others. But he was sadly lacking as a human being.

IN THE O.R.

Alda: The studio or network said we couldn't show any blood in the pilot. So Gene Reynolds shot the O.R. scenes with a red filter. You couldn't tell what was blood and what wasn't.

Metcalfe: We didn't want a laugh track, and we certainly didn't want one in the operating room. For the entire series, we would never do a laugh track in the O.R. [In other scenes] the laugh track was used modestly.

Isaacs: If a line didn't work, you could re-dub it in postproduction because the actors were wearing masks in the operating scenes and you couldn't see their mouths.

Farrell: We had a medical adviser [Walter Dishell, M.D.]. Sometimes he was on the set, and a surgical nurse was there regularly.

Swit: The actors were cutting into foam rubber [in surgical scenes]. There was a sticky kind of fake blood. I learned a certain way to hand them the instruments.

David Pollock (writer): Initially, Gene and Larry contacted doctors who had been in Korea. They gave them a list of MASH doctors to call for interesting stories and technical things about operations.

Isaacs: Most of the show's stories came out of that research. They were from interview transcripts with doctors who had been in MASH units in Korea and Vietnam.

Metcalfe: I did that research, too, for the years I was running the show. Sometimes you couldn't get the doctors to stop talking.

Levine: I remember one story about a commander who was really gung-ho, sending his troops into battle carelessly and costing a lot of lives. He came into the MASH unit, and they took out his appendix just to keep him off the line for another couple of weeks.

Davis: Once, we wanted to do an episode in which the O.R. was cold, but we had no idea why we'd need to do that. I found out from a doctor that there was a condition called thyroid storm, the surgery for which is best performed when it's cold. And we did the episode.

Wilcox: Alan wrote a script with Dr. Dishell about a transplant. We had to be especially careful with that, because the network didn't like to show blood spurting.

Katz: We did one episode in which Colonel Potter had to give a horse an enema, but in the next episode, Hawkeye was going blind. You could do some really poignant stuff.

Alda: One day, I said a line that didn't make sense. We were on location with no phones, so I couldn't call the writers' room. I said to Wayne, "Well, Larry wrote it — he must have a joke that we're not aware of." But Larry got upset: "Why did you say that? It was a typo!" So we reshot it.

ON THE SET

Alda: While the crew was setting up the lighting, we [actors] sat around in a circle. Mostly we'd just make each other laugh and get loose and connected. We'd keep that going right into the scene — we had a connection that was as real as the characters were supposed to have.

Swit: One day, Mike Farrell ran over, picked me up in his arms and said, "I said I would give this lady a lift into the greenroom." Our greenroom was like, six chairs painted green. He placed me in my chair. This was our [natural] behavior!

STANDARDS & PRACTICES

Alda: Radar had a line: "I'm not familiar with this — I'm a virgin at that, sir." It had no sexual context. But [S&P] said, "You can't say the word virgin." So Larry responded by having Hawkeye ask a patient passing by on a stretcher, "Where are you from, son?" And the kid says, "The Virgin Islands, sir."

In an episode I directed, Hawkeye calls a Korean military officer a son-of-a-bitch. The assistant director said, "You've got to shoot another version of that. They won't let it go." I said, "I'm not going to. If we censor ourselves, we're collaborating." The show went on the air the way I said the line.

Levine: We got into a big fight over the word crap. After some long ordeal, Potter said, "I'm getting too old for this crap." Just a few years later, on Everybody Loves Raymond, a catchphrase was, "Holy crap!"

Swit: When l came into the [Swamp] in one episode, there was a jockstrap on one of the beds and Margaret got into a dither about it. It was okay to have bras, panties and stockings hanging on the clothesline outside, but you couldn't show a jockstrap!

Metcalfe: After Wayne left, Fox decided to use the character of Trapper John in a new [CBS] series [Trapper John, M.D.]. We played a practical joke on the executive assigned to our show, to whom we'd send a paragraph or two on the premises of new scripts. This time, we sent him the idea that Hawkeye gets word that Trapper John has been killed. The guy called with terror in his voice: "You can't! We're doing this other show and using that character!"

The writers were rolling on the floor. Finally we said, "We're just kidding."

MEMORABLE EPISODES

Pollock: "Iron Guts Kelly" was a favorite. A general [played by James Gregory] has a one-night fling with Margaret, and he dies in the sack. They have to deposit his body on a nearby battlefield so he can go out a war hero.

Swit: Gene called in Linda Bloodworth [-Thomason] and Mary Kay Place to write an episode specifically for Margaret. We sat down and talked about her childhood and feeling that she'd let down her [military] father because she wasn't a boy. That became "The Nurses" [season five]. Jamie Farr won one of my Emmys for me when we did "The Birthday Girls" [season ten]. He was driving Margaret to the airport but got stuck in the middle of nowhere. She did nothing but yell at him: "Get going, you aardvark!"

Karen Hall (writer): I was twenty-four when I started working on M*A*S*H. They wanted to be able to say they had a woman on staff, because it was during the big push for the ERA. Alan was active in that and really wanted them to hire women.

I pitched an idea when I first went in to freelance, before I got on staff. The story would be that because Hawkeye was always leering at only beautiful nurses, a nurse who wasn't gorgeous would call him on that. Alan was afraid it would make Hawkeye look so bad that viewers wouldn't like him. I pitched that idea for two years. Finally, Alan said we'd do it — if he and I wrote it together. "Hey, Look Me Over" was the premiere of the final season.

Farrell: "Preventative Medicine" [season seven], about doing an unnecessary appendectomy on a general, was a great story. But I said that B.J. wouldn't operate inappropriately on a healthy body. Burt said, "Well, now we have a better story: Hawkeye would do the surgery, but B.J. says he won't." So he didn't, and Hawkeye did.

Maxwell: The prop guys would mush up the food for [the mess- tent scenes] to make it look not very appealing and so that I could slop it on the trays. My character would get screamed at for serving crummy food like cream-of-weenie soup. In one episode, Hawkeye freaked out because we were always serving liver or fish.

Rappaport: In "Are You Now, Margaret?" [season eight] you were led to think that Winchester was suspected of being a communist. But at the very end, you learn they're looking at Margaret. CBS did a promo saying: "Hot Lips — a Commie?" I fell off my chair. They gave away the surprise ending!

GOODBYE, FAREWELL AND AMEN

Farrell: The show ended because the cast decided to end it. It wasn't the network or the studio. Some of the cast didn't want to end it, but we finally had agreement. The network and studio said, "We need you to do a short eleventh season. If you agree, we'll agree to the rest of it."

The rest of it was that we wanted the story to be that the war ends and we all get to say goodbye. The studio said that would kill the show in syndication. I said, "It might surprise you to know that most Americans know the Korean War ended." The executive stormed out. Then he said, "You can't have an end-of-the-war episode, but you can do a two-hour movie about the war ending." We said okay.

Rappaport: The show was still hot, but we were all tired and figured, let's go out a winner. I said, "I don't want to be here three years from now, writing a show called 'Hawkeye's Place.'"

Swit: I thought we shouldn't leave our fans. And I was proven correct. We got so much mail. They didn't want to part with us quite so soon.

Alda: I wrote the two-and-a-half-hour finale, "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen," with other writers. In the middle of my directing it, the set burned down in a fire in the mountains where we shot. So I wrote the fire into the script.

Hall: There were seven writing entities on the finale. To keep the throughline, Alan would write a half-hour of the movie with each writer [or team] in his office.

Davis: One of the plots was that Alan had a breakdown and was seeing psychiatrist Sidney Freedman [Allan Arbus], who was a running character. Those scenes talking about the horrors of war were serious. One was about Hawkeye's need to have a Korean woman quiet her baby on a bus so the North Koreans wouldn't hear them and attack — but the mother accidentally smothers the child.

Metcalfe: The final day of shooting was very emotional. There must have been 200 reporters there.

Alda: We were trying to concentrate on the scene for the camera, but it felt like acting onstage with the audience in the wings. Everyone was crying.

Metcalfe: The last show we [filmed] was actually the next-to-the-last episode that aired ["As Time Goes By"]. We buried a time capsule, in which the characters had put mementos.

Wilcox: Then [the actors] decided to do a real time capsule and buried stuff near the Fox commissary. They put in Radar's teddy bear and Henry Blake's hat with fishing lures.

Swit: I put in my pink Chinese robe. Some of us put in our dog tags. A few years later, Fox was reconstructing the area and workmen dug up the time capsule.

Farr: We had packed everything in waterproof Red Cross cases. A guy with a bulldozer didn't know what the heck they were, so he just threw everything out.

Swit: It was my idea to do the time capsule, so that if anybody ever found it, they'd know there was a group there who was trying hard to do their best portraying an impossible situation.

REELZ will air an encore presentation of the recently released AMS Pictures documentary M*A*S*H: When Television Changed Forever, on Saturday 9/24 at 1pm ET/ 10am PT. The hour-long special features interviews with producers, historians, writers & cast including Mike Farrell and Jamie Farr.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #7, 2022, under the title, "Love and War."