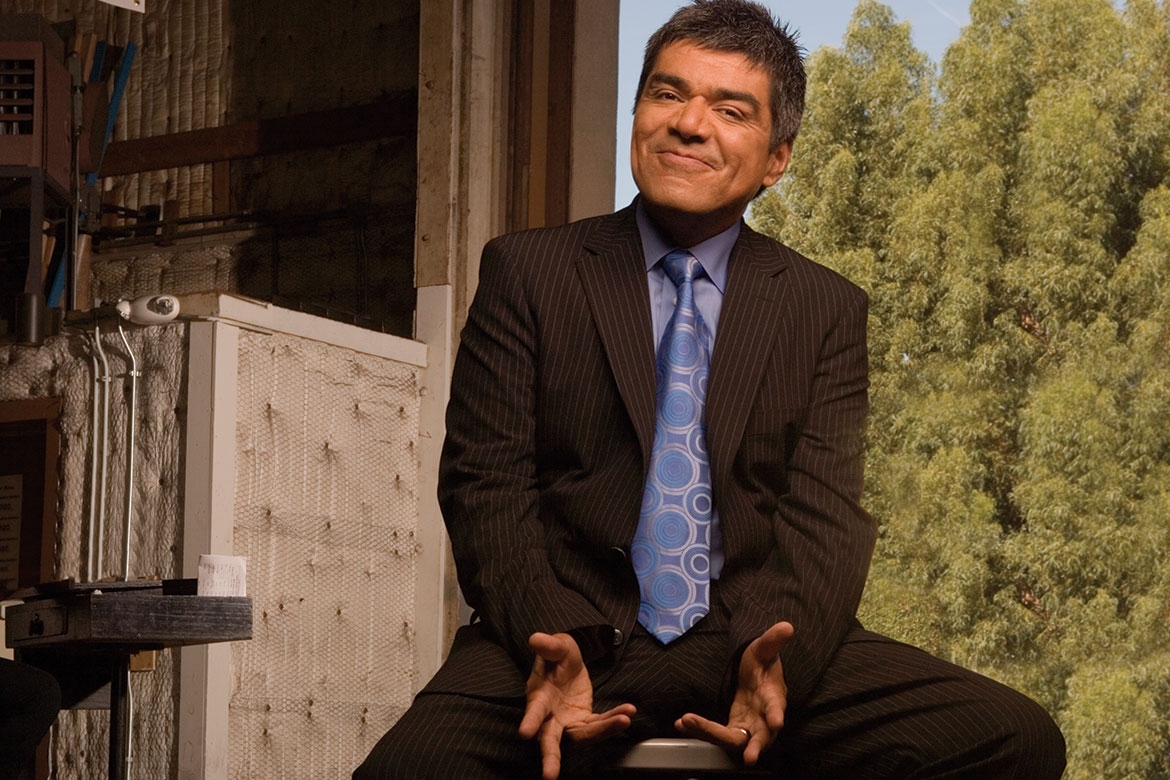

Emmy Rewind: George Lopez

George Lopez became the most successful Mexican-American in the history of U.S. television due in large part to his six-season self-titled sitcom now celebrating its 20th anniversary.

Twenty years ago, George Lopez premiered on ABC with a cast almost entirely made up of Latino actors.

The sitcom — which centered around a family of Mexican and Cuban heritage — was a trailblazer and helped pave the way for other comedies that placed Latinos at the forefront, like Ugly Betty, Jane the Virgin and the 2017 reboot of One Day at a Time.

The series starred stand-up comedian George Lopez as an aviation factory manager living in Los Angeles with his wife and two kids, along with a cast of characters including his mother, father-in-law, childhood friend and niece.

In a 1992 interview for The Los Angeles Times, Lopez expressed his desire to have a show like Seinfeld. The article went on to say, "In fact, all the comics that Lopez mentions as being on his preferred list are connected to television: [Jerry] Seinfeld, Tim Allen, Roseanne Arnold, Arsenio Hall, Dennis Miller and David Letterman. He says the format of the show isn't critical as long as the premise is good, meaning not demeaning to Latinos.

'Parts that they write are horrible for Latinos,' he laments. 'I think "Mexican" has a negative image through TV.' Lopez has vowed to never play a murderer, a drug dealer or a gang member, even if it means giving up a big payday and a Porsche.

But, until the right TV deal comes along, he wants to keep working and establishing his reputation in stand-up."

So he did. For 10 more years.

George Lopez ran for six seasons and 120 episodes and on March 27th, 2022, it celebrated its 20th anniversary.

What follows is a 2005 emmy magazine cover story written by Alisa Valdes-Rodriguez, in which she interviews the show's star during the penultimate season of George Lopez.

Ladies and gentlemen, damas y caballeros, George Lopez has landed. His ABC sitcom is in its fifth season, and the network says it's its most-watched comedy. But at the moment, Lopez has landed — literally — in a private jet in Albuquerque.

He's on his way to my city's finest hotel (not one you'd write home about), and I'm waiting — nervously — to meet him. He's come to perform his stand-up act at a casino on the outskirts of a town that itself is something of an outskirt.

In a past incarnation, I was a writer for the Los Angeles Times and Boston Globe, a job I adored. But I quit that job and became a novelist, living here in Albuquerque. I look around me, a little ashamed. George has hit the big time. I hope he isn't offended by our dust.

I should let you know, before continuing, that George and I recently shared a page with Jennifer Lopez in Time magazine, where we were all named among the top twenty-five most influential Hispanics in the nation. Imagine: a basically anonymous writer finding herself on a page with those two! It's like being the lone hamster at a designer dog show. So I feel a bit like an impostor as I wait for George. Like, I shouldn't have been on that stinkin' page. He's freakin' famous!

But famous is almost an understatement when you talk about George Lopez. This actor-producer-director-stand-up comedian — and rabid golfer — rocketed to stardom with the success of his semi-autobiographic family comedy, George Lopez. It has earned him enough to land a duffer's dream — a home in Pebble Beach, California, footsteps from the legendary course's fifteenth hole. Perfect for a guy who once turned down $130,000 to do a forty-five-minute set before a Rod Stewart concert because he had a golf date. And one who was back on the links just three weeks after a kidney transplant.

At forty-four Lopez is, in fact, the most successful Mexican-American in the history of American television. He is one of only three Latino men to star in their own long-lived prime-time sitcom on mainstream U.S. television. The others are Cuban Desi Arnaz and Puerto Rican Freddie Prinze, Sr. Nice club to belong to. Dude's famous enough that he got Punk'd on MTV. Me? Only time I get punked is when my agent crank-calls me out of boredom.

My cell rings. It's George's assistant. They're ready for me to come upstairs. Upstairs? The stealthy Mr. Lopez arrived when I wasn't looking. The assistant and I ride the elevator to the top floor, and I feel like a lowly reporter again. Digital recorder? Check. Pad of paper? Check. Pen? Check. We enter a suite and there he is, in jeans, a T-shirt and comfy brown loafers. Looking slender, youthful, and — dare I say — handsome. He attributes his glow to the fact that his wife Ann gave him one of her kidneys recently; his own were failing due to a genetic infection of the urinary tract.

George sits across the coffee table from me, his body turned sideways. My amateur psychological analysis tells me he's protective of his privacy. He doesn't make eye contact. Like many comics, he can be dour in person, pensive, serious. You get the sense this is a man who never stops thinking.

Given his background, Lopez's reflective demeanor is understandable. Born into poverty in a nondescript section of L.A.'s San Fernando Valley, he was two months old when his migrant-worker father flew the coop. His illiterate, emotionally unstable mother bailed out when he was ten, leaving him in the care of his grandparents. The towering figure in his childhood was his out-and-out mean grandmother. How mean? He recalls in his 2004 autobiography Why You Crying?: My Long, Hard Look at Life, Love, and Laughter, asking, as a child, "Where do babies come from?" She replied: "Whores. Now go play."

Bright but unfocused in his youth, he found inspiration in the renegade comedy of Freddie Prinze and Richard Pryor. He spent more than two decades honing his chops on the standup circuit, wallowing in self-loathing and alcohol and internalizing the sting of his abuela's cruelty. Eventually, he channeled her derision into the hilarious, albeit dark-edged sensibility that has fueled both his stage act and sitcom.

"So, I thought I might do this as a Q&A," I say. George shrugs. He reaches for his venti cup of something hot from the Starbucks downstairs. "So," he asks, "what do you want to know?"

I can tell he thinks I'm just another annoying reporter. Now that I've been interviewed by a few of them myself, I know how he feels. I tell him who I am, ask if he remembers our sharing that page in Time with Jenny from the Block. He looks me in the eye for the first time, a brow up. I give him a couple copies of my books, signed, feeling like an arrogant hamster sucking up to a prize bulldog.

"You know what?" he asks as he looks at them. "I think my wife has read your books. As a matter of fact, I know she has." He smiles. His shoulders relax a little. I tell him that I think he's way better at talking about George than I'll ever be, and that I'd like to approach this piece by just letting him talk into a recorder. He agrees. And it goes a little like this:

Me: Why do you want to keep doing stand-up and coming to places like Albuquerque?

George: I've always had this desire to make people laugh, from as far back as I can remember. When things were great, like now, and when things were really bad, I always wrote something. Not necessarily in script form, but I always wrote down my thoughts. I always had thoughts in my head that were different than everybody else's, and I always said things at inappropriate times — I got in a lot of trouble in school for that. Not like getting thrown out of school, but just set aside from everybody else. The things they'd write on my report cards — "He doesn't know when to stay quiet," and "He doesn't work well with others" — are the things that have made me successful in my business. So when I talk to kids, I tell them not to edit themselves and not to let anybody suppress them, which is important because we come from a culture of suppression. Instead of, "Go out and get dirty!" it's, "You better not get dirty!" Or "I better not hear you!" or "Don't make me come in there!" Those are the things that tortured me as a kid.

But the reason I do stand-up is because I can be free and not have to worry about somebody not liking it. I've gotten to the point where I don't care whether they like it or not. Now, I've never become disconnected from [my fans]. I'm afraid to become disconnected from being a real comedian because I don't know what it's like not to be a comedian. It's like breathing. I've always had it around me — these are transcripts from my [stand-up] shows."

[George fetches an enormous binder, maybe seven inches thick, from the dining table and shows it to me.]

I'll go through this today. It's just part of me. I cannot stop doing it. Plus, I want recognition. I've sold out the Arrowhead Pond [the arena in Anaheim now known as the Honda Center]. My picture's in the lobby of the Universal Amphitheater. I had eleven consecutive sold-out shows there. I sell out everywhere I go. I sell tickets not only to Latino people, but to everyone. Yet I don't get the recognition that Chris Rock does. I had a special on Showtime [Why You Crying?] that was highly rated — it should have gotten nominated for an Emmy, but it didn't. They ran it on Comedy Central; it got huge ratings. I'm going to keep doing it until I get some sunshine for being a stand-up.

Me: I like something you said in the L.A. Times about the way the media is presenting your show and Freddie Prinze, Jr.'s show [ABC's Freddie] as "the Latino Hour." You don't love that. Why not?

George: This country is based and founded on bias. It was taken over, you know? The media feel like they have to describe minorities by what race they are, instead of by the good work they do. So when Freddie Prinze, Jr., was doing Scooby-Doo and She's All That, he was Freddie Prinze, Jr., and somehow when they associate him with me, it becomes a "Latin Hour."

Freddie didn't really seek it out — I sought it out. The way I looked was obviously different from everybody else, so I had to play into what I looked like. I could not pretend that I wasn't what I was. I like talking about where I came from and how we had very little and how we made things out of nothing.

It's probably easier now than it would have been, having back-to-back [Latino] shows. And they're connected to each other, really. My executive producer [Bruce Helford] is the executive producer and creator there on Freddie. So I don't think they're anything other than two sitcoms. I mean, when [Everybody Loves] Raymond [was the lead-in to] King of Queens, it wasn't the Italian hour. Even in the seventies, if you had two Black shows togther, they wouldn't do that. But now?

Me: In some ways, TV seems to be regressing. I saw an episode of I Love Lucy recently — Lucy and Desi were going to Cuba to meet Desi's family, and the family was presented as these upper-class people wearing hats. Hispanics are rarely presented that way on TV now. Other than your show, we're maids or whatever.

George: I know.

Me: Why is it that you've been able to to rise above the offensive stereotypes, while so many others have not been able to? Or weren't allowed to. What is the secret?

George: Early in my TV career, when I would get copies of the script and they weren't in the condition they should have been, my wife would tell me, "You better go in there and talk to them and change these things. It's your name on the show, and when it doesn't succeed, you're the one that's going to go down. This is your shot, and you have to speak up for yourself." That wasn't always comfortable. I'm very good at it now, but back then I wasn't.

That was five years ago. It was all new to me, and I thought, "I've got to learn this." I've always been one of those guys who, if someone asked me, "Do you know how to do this?" I'd say, "Absolutely," even though I didn't. But I could watch and learn quickly. I directed the show last night, for the first time. Though I'd never directed before, I'd seen enough, and what I didn't know, I learned as we went. I learn really fast.

So, as I said, my wife made me stand up for myself. But when other minority actors or writers get to that point, they don't always speak up. TV executives will say, "Anybody have an objection to this character working in a donut shop? Say something right now." And nobody will say anything, so I guess it doesn't matter. But it does matter. All of that matters. Like on Seinfeld, [when a character] says, "They didn't really get me at Warner Bros." You know what? They don't get anybody. You gotta make them get you. You gotta say, "This is what I want to do, and I won't do this or I won't do that. "

Unfortunately, not a lot of people can do that. I couldn't do it. I never, ever spoke up for myself, and then once I did it, I liked it. I knew that I was getting more results. Every week that the show went on, and we started to get more attention, I became more secure. So that's the advice I'd give anybody who wants a TV show, no matter their background: Don't compromise your vision, and don't let anyone tell you how you're supposed to be. You are the best judge of that. The viewers will recognize when it's genuine, and they'll watch.

What's next for George? He tells me he'd like to retire from the series after a few more seasons, then try some more dramatic acting in film. He has already appeared in dramatic roles in Real Women Have Curves and Bread and Roses. And he's been in the family feature The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D. He's also set to star in the upcoming The Richest Man in the World, about the poorest man in the world who gets to walk in the shoes of the richest.

Can he relate? "I'm a lucky guy," Lopez says with a grin. "I've done everything I wanted to do in my life. So anything else that comes is just icing on the cake."

A longer version of this article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #6, 2005, under the title, "King George"