Mac and Sally's Golden Anniversary

A half-century since the premiere of McMillan & Wife, the appeal of Rock Hudson's first television show lives on.

Fifty years ago, the idea of a movie star doing a television series wasn't exactly unheard of, but it was far less common than it is today. So, when NBC announced that Rock Hudson would be joining its lineup in the fall of 1971, people noticed.

After all, not only had Hudson been a successful Hollywood leading man for more than 20 years, his most notable television credits at the time — other than the usual awards shows and talk shows — were a 1955 episode of I Love Lucy (as himself) and three uncredited appearances on Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In in the late '60s.

Hudson's new show, McMillan & Wife, was one of three spokes in the programming wheel that comprised the network's NBC Mystery Movie on Sunday nights. The format was something of a hybrid. Instead of a new hour-long episode every week, each McMillan & Wife was a 90-minute telefilm that rotated with installments of two other titles — Columbo, starring Peter Falk as a disheveled, deceptively brilliant L.A. homicide detective, and McCloud, starring Dennis Weaver as a horseback-riding New Mexico cop relocated to New York City.

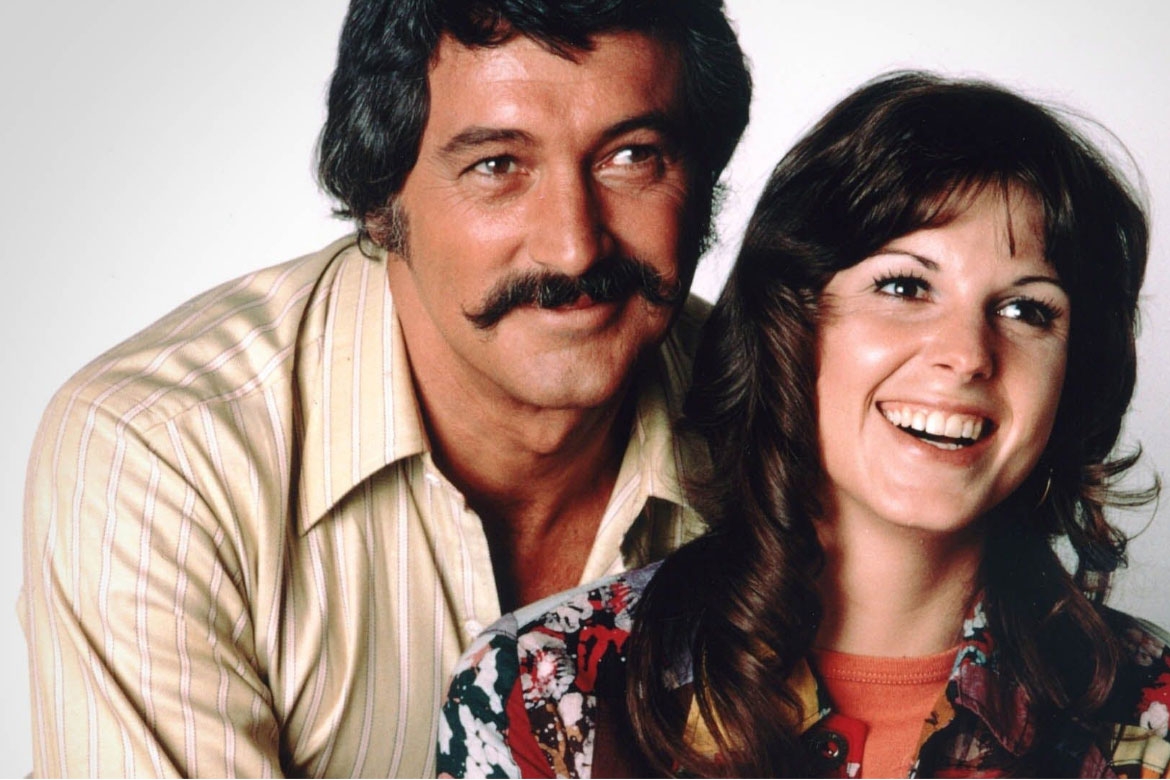

In McMillan & Wife, which premiered on September 17, 1971, Hudson was San Francisco Police Commissioner Stewart "Mac" McMillan, who solved crimes with his not-really-stay-at-home wife, Sally, played by Susan Saint James.

Think The Thin Man for TV, with a little Murder, She Wrote and a bit of Gidget on the side.

The premise was an ideal fit for Hudson's two most established film personas — the sturdy action hero and the flirty rom-com hunk — and after a slow start became a steady performer for NBC. Its final episode aired on April 24, 1977.

The success of McMillan & Wife, Columbo and McCloud sparked the addition of a fourth Sunday Mystery Movie, Hec Ramsey, starring Richard Boone as a turn-of-the-20th-century lawman who embraces ballistics, forensics and other emerging investigative techniques.

In 1972, NBC expanded the Mystery Movie brand to Wednesday nights. Like the Sunday lineup, all were produced by Universal Studios and all featured iconic composer Henry Mancini's haunting opening theme music.

Over the next few years, the Sunday and Wednesday additions included:

• Amy Prentiss, a spinoff of Ironside with Jessica Walter in the title role of a young San Francisco police detective who becomes the chief when her predecessor dies unexpectedly.

• Banacek, starring George Peppard as Boston-based insurance investigator.

• Cool Million, starring James Farentino as a suave former CIA agent turned private eye whose services require a fee of one million dollars.

• Faraday & Company, featuring Dan Dailey as a private detective who returns to Los Angeles after a lengthy stint in a South American jail for a crime he didn't commit and partners with a son he never knew he had.

• Lanigan's Rabbi, about small-town police chief Paul Lanigan, played by Art Carney, who teams with his best friend, Rabbi David Small, played by Bruce Solomon, to solve local mysteries.

• Madigan, in which Richard Widmark revisited his 1968 film role as a no-nonsense New York City police detective.

• McCoy, headlined by Tony Curtis as a con man and thief who uses his larcenous skills to outsmart crooks and return stolen spoils to their rightful owners.

• Quincy, M.E., starring Jack Klugman as a medical examiner for the Los Angeles County Coroner's office.

• The Snoop Sisters, with Helen Hayes and Mildred Natwick as a pair of mystery-writing siblings who dabble as amateur sleuths.

• Tenafly, led by James McEachin as a former cop who becomes a private investigator in Los Angeles.

Although not without individual merits, most were short-lived, and today, the original three remain the most enduring of the group.

Within the original Mystery Movie troika, McMillan & Wife stood out structurally and tonally.

Columbo and McCloud featured lone-wolf leads, but McMillan & Wife was built around teamwork and relationships, and not just between Mac and Sally. Affable associations were established by a small band of characters made up of the couple's close-knit friends and colleagues, led by John Schuck as the fastidious Sergeant Charles Enright and Nancy Walker as Mildred, the McMillans' wiseacre housekeeper.

Although Falk's shambling turn as the trenchcoated Columbo was not without levity, Columbo and McCloud were, for the most part, straight-ahead dramas. McMillan & Wife had a lighter touch, with swift banter between Mac and Sally and reliable comic relief supplied by Schuck and Walker.

One of the busiest TV actors of the era, Walker was also known as Ida Morgenstern, mother to Valerie Harper's Rhoda on CBS's Mary Tyler Moore Show, and Rosie, the diner waitress in a series of popular commercials extolling the absorbency of Bounty paper towels — and popularizing the catch phrase "the quicker picker-upper." Walker, who died in 1992, eventually exited McMillan & Wife to co-star in the Rhoda spin-off and later took the leads in two short-lived ABC sitcoms of the mid-to-late 1970s: Blansky's Beauties and The Nancy Walker Show.

During that transitional period, Saint James and Schuck also eventually left McMillan & Wife, which became just McMillan — minus the Wife. Saint James's Sally and Walker's Mildred were dispatched (Sally died in a plane crash, Mildred left to open a diner on the East Coast), and Schuck's Enright explored other career options, while Martha Raye arrived as Agatha, Mildred's sister, who became Mac's new housekeeper.

Schuck moved on to the role of robotic cop Gregory Yoyonovich opposite Richard B. Shull in ABC's Holmes & Yoyo, a short-lived sci-fi police comedy (think Adam 12 meets The Six Million Dollar Man with a farcical twist). Saint James later re-emerged with Saturday Night Live alum Jane Curtin in the groundbreaking CBS 1980s hit sitcom, Kate & Allie.

McMillan & Wife creator Leonard B. Stern had also launched Holmes & Yoyo, produced Get Smart, directed He & She and was associated with many other TV favorites. In an interview with the Television Academy Foundation in 2008, Stern explained the genesis of McMillan & Wife: "I wrote a script on spec because I felt I wanted to do a mystery. Why? I didn't know at the moment."

As Stern put it, "the realization" to create a mystery series with comedic overtones and a "surprise" ending simply popped into his head one day. After writing "encapsulating mysteries in junk form" for some time before, Stern said, he decided to finish a complete script.

During a subsequent weekly poker night with a few card-playing cronies, a friend and colleague asked Stern about the script and suggested Rock Hudson for the lead.

Both in lengthy contracts with Universal, Stern, who died in 2011, and Hudson, who died in 1985, had known one another for years, but had lost touch. But an associate of Stern's was close friends with Hudson's manager, Flo Allen, and asked Stern if he could send her the script. Stern consented, Hudson read the material, liked it, and was interested in bringing it to life with one condition:

The property would have to be presented as a one-shot TV movie, as Hudson had no interest in working on a weekly series. Stern agreed.

Although he had been a marquee name in the film business since the 1950s, Hudson was not opposed to pursuing television. In a 1971 interview with journalist Bobbie Wygant, he said he took the role in McMillan for a simple reason: "They asked me. I had never been asked before."

After Hudson was cast as Mac, Schuck came aboard as Enright.

But who would play Sally?

Saint James was a prime candidate. Also contracted with Universal, the actress with the unique voice she describes today as "scratchy," had just completed a three-year run on NBC's The Name of the Game. One of the producers of that series had written a script for her and, as she remembers, "I was off to Europe to shoot a pilot."

But in the middle of filming, Saint James was instructed by her agent to return to the States to meet with Stern and Hudson about a leading role in a new TV show.

"Rock was having lunch with every actress in Hollywood who was in my kind of category," Saint James says.

The following day, she received a phone call from her agent, who said, "That's it. Go to wardrobe. You got the job."

Years later, Hudson joked with Saint James about why she won the role. As she recalls, "He told me, 'I was gaining so much weight just having lunch with people, so I figured, Let's just go with this woman because I don't want to have any more lunches.'"

In truth — and as Stern affirmed in 2008 — Saint James "was a delight. We talked to many gifted actors. But I wanted a new face there," one with "subtle" overtones. "I say 'subtle,'" he explained, "because audiences don't pick up on [an actor's uncommon appeal] until they think of it retrospectively."

Eventual film stars Diane Keaton and Jill Clayburgh, each with a small list of credits at the time, were among those also considered for Sally.

As Stern explained, "Our casting person in New York knew of them and knew talent. He was a divining rod when it came to gifted young people. And Rock felt comfortable with Susan."

Although Saint James was 21 years younger than Hudson, "She turned out to be an ideal choice," Stern said, "because she had an innate sense of mischief. That's what the role called for...it was spawned by The Thin Man. Nick and Nora [Charles]" — the married mystery-solvers created by novelist Dashiell Hammett and played by William Powell and Myrna Loy in a popular series of films in the '30s and '40s — "were in a different age bracket. And I wanted someone who could handle wit and lunacy and the fun would be equally as important as the mystery...or the relationships would be."

Of the age difference between Mac and Sally, Stern said, "I wanted it, so it's not May-December but it was two different generations."

But if there ever were to be a reboot of McMillan & Wife, Saint James doesn't think the age-disparate casting would work. "They couldn't do that today," she says. "People would probably say, 'What the heck? Can't he find a girl his own age?'

"But at the same time," she adds, "Rock didn't read [on camera] as older. He was just so handsome, while the backstory that Sally's father was Mac's mentor was never fully explained on the show. That's really how they got to know each other."

The only other character on the series who could be considered a senior was Walker's Mildred. But as Stern explained, "In the pilot, there was no Nancy Walker character. We referred to Mildred. But she had such a palpable presence through her notes that we said, 'Why not write her?' And we did."

So, at the onset, with Hudson, Saint James and Schuck in place, Stern approached ABC, CBS, and NBC, the latter of which he believed "made the best offer and the best promises."

Subsequently, production then began on the show's pilot, "Once Upon a Dead Man," a significant portion of which was shot in San Francisco. The filming "went swimmingly well," Stern said. "Everybody enjoyed each other."

The "Dead Man" pilot was also well-received by viewers and executives at NBC, prompting the network's interest in continuing the adventures of Mac and Sally on a regular basis. That meant Hudson would have to reconsider his decision to not do a TV series.

Stern reapproached Hudson. But the actor eventually agreed to reprise Mac in a consistent format for three reasons: he enjoyed working on the initial film, he trusted Stern and, as he told Wygant, "It's a marvelous idea for a show."

Hudson also liked that the series would air monthly, as opposed to weekly.

"We're doing an hour-and-a-half film," he said, "which, of course, gives us the opportunity to perhaps tell a little bit better story...in more detail...as opposed to a half-hour show or an hour show where you have to skip over essentials and not have time to shoot it...within the time-slot in which you're given to tell the story."

Not only did the rotating 90-minute style appeal to Hudson but, according to Saint James, the concept was "born out of the Name of the Game" format.

That show "made a splash," she says, partly "because it was an hour-and-a-half-long. And the viewers liked that."

From the beginning, some wondered if Hudson doing a TV series would jeopardize his box-office appeal.

"Each has its own attraction," he told Wygant, while hoping that McMillan & Wife would get "picked up for next season. And that's trying to foretell the future."

It was a prediction that boded well for Hudson's television debut, after years on the big screen with movies like Giant (1956), co-starring Elizabeth Taylor and James Dean (for which he earned his lone Oscar nomination), and Pillow Talk (1959), starring Doris Day — his two personal favorites among his films. Like Hudson, Day found fame on a hit TV series (The Doris Day Show, CBS, 1968–1974), while their interplay in the movies — which also included Lover Come Back and Send Me No Flowers — presaged, to some extent, his interactions with Saint James on McMillan & Wife.

"Rock's big strength was romantic comedies," says Saint James. "That's what he did best. All of those movies he did with Doris Day were my favorites growing up, and I just fell into that with him on McMillan & Wife. We both just loved doing romantic comedy. They're fun to do, and I had no trouble looking lovingly at Rock Hudson. I mean, he was a matinee idol!"

Additionally, Saint James credits Hudson's "very light-hearted" manners. "He didn't bring doom or gloom" to any set he worked on or character he portrayed. "He'd let his agent negotiate the details of things like what time he wanted to leave for the day. But if it was a big scene and it was late, he would stay to complete the day's work. We became good friends. He was easy-going and funny. I have outtakes from the show on 16mm film which are hysterical. We all were happy, and we just clicked."

As for Walker, "My mom and dad knew her really well," Saint James says. "She was famous for her comedy. With that wild red hair and that flat-talking way about her, she was hysterical and the perfect foil for Sally. And Rock loved her."

"I was in awe of Nancy," Schuck says. "This was one of the great Broadway stars of all time. And my old dream was to do Broadway. That was the reason I went into acting. I had done a lot of theater. But I had never done Broadway. And Nancy had this extraordinary career with dance and on stage, and in movies. So, she was like a little goddess to me.

"From Nancy," Schuck continues, he "learned discipline. From what a pause could mean, as opposed to a reaction. All these things about timing, which she was so good at. It was grand fun. I picked her brain relentlessly to get stories [of Hollywood and Broadway]."

On McMillan & Wife, Hudson's towering six-foot-five height opposite Walker's petite four-foot-eleven frame was a frequent source of humor, as on the occasion when Mac and Mildred danced the tango.

"Rock could not stop laughing through that one," Saint James recalls.

In an interview with TV Time magazine in 1990, Walker said, "Rock was the most generous, affectionate man I've ever known."

"The Rock that I knew was generous," agrees Schuck. "I distinctly remember him looking at me one day and asking, 'Do you have a musical instrument?' I said, 'Well, growing up I had a piano, and I had always wanted another one.' He said, 'Let's go buy a piano.'"

A week later, Hudson took Schuck to lunch and "over to Beverly Boulevard where he helped me pick out a little baby grand, which I had for thirty years. What made him do that? I have no idea. It was out of the blue. That was the kind of person he was.

"I think the giving of objects like that...extravagant objects," Schuck says, "usually comes from people who have emotional difficulty with saying 'I love you' or 'Are you really my friend?' Whatever the relationship happens to be. But I think Rock fell into that category."

Schuck also remembers Hudson's affection for other friends and colleagues on the McMillan & Wife set: "We had a cinematographer by the name of Milton Krasner, who had to be in his eighties. putting in 16-, 18-hour days, five days a week. Milton was this wonderful man who shot everyone from Marilyn Monroe to you-name-it. He was a remarkable guy. But he lit scenes very slowly, so the time between scenes could be lengthy. And about the second year, someone approached Leonard Stern and said, 'Get rid of Krasner. He's costing us too much money.' But Milton lit the scenes like a movie. It didn't look like a television show at all."

According to Schuck, that's when Hudson stepped in. Upon learning that Krasner — who was nominated for six Oscars and won for the 1964 aviation drama Fate Is the Hunter, starring Glenn Ford — might be fired, Hudson told Stern, "If you fire Krasner, I'm outta here."

Needless to say, Krasner stayed.

"Rock created a marvelous atmosphere," Schuck says, reiterating his and Saint James' thoughts. "We had a very happy set. He treated everybody as peers. There was no star crap going on, or any of that stuff. He set the tone. If there was any single reason why the show succeeded, it was because of the joy and ease he brought to the set. He loved the show. He really did. The strength of our show was the chemistry between the actors...the relationships that we all had together off-screen. There was a genuine affection that just crept through on-screen."

All of it was in keeping with Hudson's carefree spirit, which was further exemplified one year, when Schuck had lost some weight. As Saint James recalls, "Rock was like, 'John — you're too handsome. You can't be funny if you look like that."

The same, of course, could be said of Hudson's appearance, which altered only slightly through the run of the show.

For example, in the first season, he sprouted a mustache, which he eventually shaved off.

Though, as the actor told Wygant, he found it "curious...not necessarily interesting...but curious" that his fans had such a mixed reaction to the mustache. It brought "a violent response, either for or against," he said. "Certain people....ladies..." in particular, would approach him and say, "Shave that damn thing off, or I won't go see any one of your movies!"

Hudson also claimed he received the opposite response such as, "Oh — it's just great."

Either way, Hudson always won over his co-stars. Schuck calls him "an unsung actor" who sought to "better his craft. He worked very hard at it. He did some very daring things. During the course of McMillan & Wife, he wanted to do more theater. So, he went out one summer and did a stage musical like I Do, I Do, with Carol Burnett."

But it's the laughter that Schuck remembers the most. He recalls "more than a few times when Rock could be like a little kid."

One such scene occurred the first time the actors filmed the show in San Francisco. "It involved two phone booths," Schuck says, "where we were making calls at the same time. It was quite complicated. It was popping in and out to get information from each other and all that stuff. And I have a photograph that I prize of Rock and I leaving the phone booths after the director yelled 'Cut!' And we are laughing. We had known each other a grand total of about an hour at that point. So, right off the bat, there was this camaraderie."

There was also a sequence later in the series, which was filmed at night with a moving vehicle. "We pulled up in a car," Schuck recalls, "drew our guns, stepped quietly up this walkway through the entrance of this house and pushed on the door. But it had locked, and we couldn't get in. So, we went around to the back of the house and, [it was] just as we're shooting a master shot of that. And Rock touches the door, and this time it opens. But it's not supposed to open. So, he turns to me and says, 'Uh oh.' And we start laughing because we can't get anything done."

Although it could clearly be a loose set, "Rock was also a great example of preparedness," Schuck says. "He had a strong work ethic. I just can't say enough nice things about him...especially since his leaving this world was not the best thing that ever happened. He was flawed only in the sense that he surrounded himself with people who were more interested in their own selves rather than his well-being. And so, he received a lot of bad advice."

It was not until shortly before his death from AIDS, on October 2, 1985, that Hudson's homosexuality, which had long been rumored, became public. A story in People magazine in August of that year was the first mainstream report of his diagnosis in relation to his sexuality.

Prior to becoming too ill to work, he had been costarring on the ABC drama Dynasty as Daniel Reece, a horse breeder — and the biological father of Heather Locklear's Sammy Jo Carrington — who becomes romantically involved with Krystle Carrington, played by Linda Evans. When he was unable to continue, his character was written off the show.

News of Hudson's condition was met with shock as well as sadness, but it also put a famous face to a medical condition that was still largely misunderstood and unjustly stigmatized. Although Hudson's openness about having contracted AIDS did not eliminate the stigma surrounding the illness, it was an important step toward raising awareness of the syndrome and, importantly, funds for medical research.

A month before his death, Hudson sent a telegram to the Commitment to Life AIDS benefit in Los Angeles, which he was unable to attend due to his weakened condition. It read: "I am not happy that I am sick. I am not happy that I have AIDS. But if that is helping others, I can at least know that my own misfortune has had some positive worth."

Although McMillan & Wife unfolded in the hilly topography of San Francisco, that's not where the series shot for most of its run. "The more successful the show became," Schuck says, "the less we filmed in San Francisco. That's why, in later episodes, you rarely see a hill. Everything's flat. All the cars are parked flat.

"In our first season," Schuck says, "we did not do particularly well. I think we were the second-lowest rated of the [Sunday Mystery Movies]. But Columbo took off, and then people got in the habit of watching in that time period, and that's when we began to develop our audience. By the second season, we had created our own fan base and were doing quite well."

Also, by that time, Schuck adds, "the show began to get better. The writers became more familiar with who the characters were. We knew who we were, and so forth. And some adjustments had been made in terms of how you approach things.

"For example, Charles Enright, my character, was pretty much incompetent. He's funny, sweet, we like him. But to me, I was playing somebody who was an incompetent person who just messed things up. It was not a challenge nor a lot of fun to play.

"And I went to the producers and said, 'Listen, I see him not as a buffoon, but as an overachiever. He's the one who is too loyal; he tries too hard. And because of that quality, I think we found much more to work with there."

The likability factor was, and remains, essential to the longevity of McMillan & Wife's appeal.

But as Schuck assesses, "Any actor has their strengths and talents. And most of those things are God-given — your looks, your personality — and not developed. So, I can't claim anything about myself in that way. It's just who I am.

"I guess I am likable," he muses. "That's a quality in me. But I have nothing to do with developing that."

"Likability is the key to every good performance," says Saint James, in her signature sandpapery tone. "Yes, I have that voice. But I never manipulated it or used it in a certain way. It's just me."

Throughout the show's run, the McMillan & Wife actors jelled with their roles and the audience at home. And while there were character and premise changes through its five-season run, the show's basic structure remained the same, with a solid base of creatives pulling the appropriate strings behind the scenes.

For one, Schuck says the show's first story editor, Oliver Hailey, "was a wonderful playwright. He was there the first few years, but he didn't have much television history. And then young Steven Bochco came aboard. He had already quite a bit of experience, and the scripts changed about the third season."

From a personal standpoint, Schuck credits McMillan & Wife with helping to build his fan base. "It allowed me to have my theatrical career in New York. My first Broadway show was playing Daddy Warbucks in Annie. And I replaced Reid Shelton, who was the original, and I stayed."

(Coincidentally, Allison Smith, who performed with Saint James as a child in Kate & Allie, starred in Annie during Schuck's run.)

"There were better singers than me, stronger actors, all over the place," Schuck explains. "There's always someone better than you. But one of the things I had — after six years on Annie, was a built-in TV audience. And the show's producers hired me — I'm pretty sure — because I brought a good portion of that audience into the theatre.

"In this way," he continues, "I'm very grateful to McMillan & Wife, which I think did that more for me than any or all of the movies I did. Being on the show taught me how to handle my career, as far as audiences are concerned. So, I have a debt of gratitude for that and to Leonard Stern, who hired me in the first place."

Schuck remained with McMillan & Wife until the end, albeit to a lesser extent in the final season. That's when the show morphed into McMillan, leaving Hudson as a solo lead, more akin to the single-star format of Columbo and McCloud.

"I had never signed a contract with the series," Schuck says. "I freelanced. And it probably cost me a lot of money. But I wanted my independence. So, when I did Holmes & Yoyo we worked out a deal where I would do both shows."

Schuck's Enright was promoted to Lieutenant and became Deputy Chief of the San Francisco Police, which took him away from his position as Mac's liaison. Richard Gilliland joined the cast as Enright's replacement, Sergeant DiMaggio, who frequently introduced himself with the clarification that he was "no relation" to baseball legend Joe DiMaggio.

Schuck's now-limited scenes would be filmed at night. "I don't think I was anywhere else but my desk in that last season," he says with a laugh. "They literally had this two-piece set behind me with a plant, and I did most of my scenes on the telephone.

"The best concept of the show was with Susan," Schuck says. "She was terrific as Sally, and the show was strange and just not the same without her."

Saint James left, she says, "Because my contract was up, and I wanted to try film."

In the 1970s, however, actors making the transition from television to feature films "was a challenge," she says. She met the challenge with well-received performances in movies like Outlaw Blues (1977) with Peter Fonda, and Love at First Bite (1979), with George Hamilton. But television was her ideal platform. "I eventually realized, you know, 'Love the one you're with,'" a philosophy that led to her return to TV with the super-hit, Kate & Allie.

Since 1981, Saint James has been married to Dick Ebersol, the veteran television executive, senior adviser for NBC Universal Sports and Olympics — and, from 1980 to 1985, executive producer of Saturday Night Live. And she is very much aware of the special place that McMillan & Wife holds in the heart of its fans, particularly when it comes to her TV spouse Hudson.

The two actors remained in contact over the years, and Saint James has fond and poignant memories of two Hudson tributes that transpired, before and after his passing in 1985. She was in New York for the first tribute, when he was alive.

As Saint James remembers it, "I got a call from his manager, who said, 'Rock is being honored in Atlantic City and he'd love for you to come down there and be one of the speakers.' There were four women who were asked, including Carol Burnett. And they all knew Rock really well or had worked with him. So, Dick and I thought, 'Well, this will be fun,' especially because Dick had also known Rock socially in Hollywood for years."

The event took place on a Saturday night, James and Ebersol had flown in the Friday before. But the next morning, there was a hurricane, and none of the other speakers could attend the event except Saint James. "So, Rock joked and was like, 'Okay — it's all on you...stretch it out. Make it long.'

"But by the time it was all over," she adds, "the skies were clear, and they sent a helicopter to take him back home. And he invited Dick and I back to his apartment with his press agent, and none of us until the sun came up on Sunday morning. We stayed up all night and had the best time, telling hilarious stories. And I felt like that was a blessing because Rock had recently had open-heart surgery. He smoked as a younger man and had a serious heart condition. So, he looked kind of gray.

"As it turned out," she continues, "he was already suffering from either HIV or AIDS and we didn't know that; I don't even know if he knew it then. And it wasn't long before he died."

The second Hudson tribute that Saint James attended was hosted by his friend Elizabeth Taylor at his home in Los Angeles. According to Saint James, Taylor told her, "You've actually worked with Rock more than any of us because you did years of movie-length shows."

But between those two events, Saint James had the chance to speak with Hudson, shortly prior to his death. "I got to tell him, 'I love you, and I'm praying for you,'" she says.

"It was so perfectly special that we got to spend time together," either at Hudson's apartment that night after the event in Atlanta, or during their last conversation on the phone.

"It was a gift," Saint James says.

No doubt many McMillan & Wife fans share a similar sentiment about the show's place in television history.

Herbie J Pilato is the host of Then Again, a classic TV talk show streaming on Amazon Prime, and the author of several books about television. For more information, visit www.HerbieJPilato.com.