Julia literally changed the face of television with a series of firsts.

It was the first TV series to feature a non-stereotypical African-American, specifically, a sophisticated African-American female, in the lead of a 30-minute comedy or a one-hour drama. It was also the first show to combine those genres, becoming an inaugural weekly half-hour dramedy, filmed with a single camera, without a live studio audience, or a laugh track.

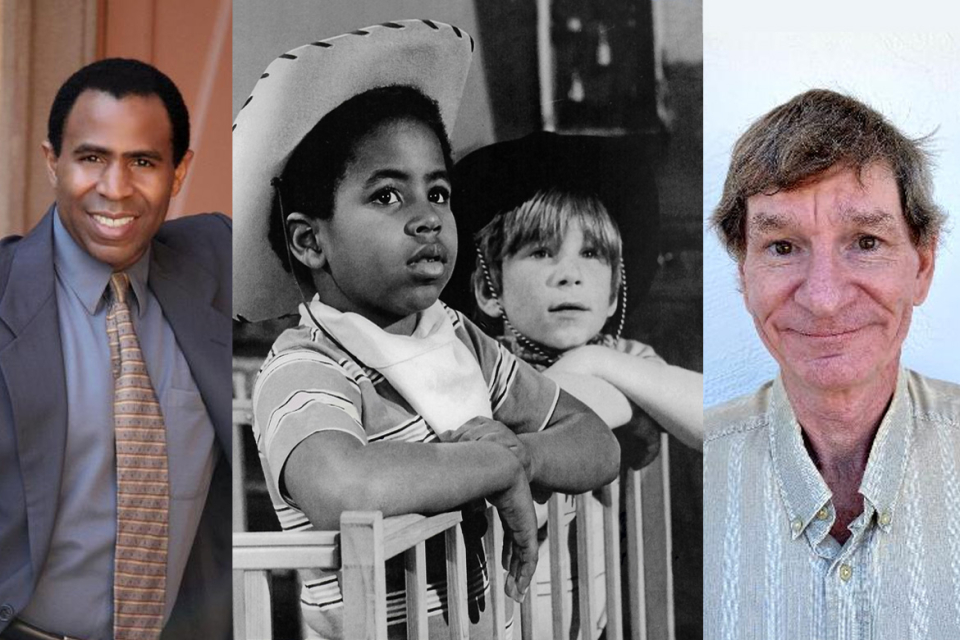

A ground-breaking program across the board, Julia originally aired on NBC from 1968 to 1971 and starred Diahann Carroll as nurse Julia Baker. She was widowed and the single parent of a six-year-old son named Corey played by Marc Copage. After Julia's husband, an O-1 Bird Dog artillery spotter pilot, was killed in the Vietnam War, she and Corey moved into a stylish, integrated apartment building.

Their neighbors included Marie Waggedorn, played by Betty Beaird, and her son, Earl J. Waggedorn, Corey's same-age best friend played by Michael Link.

In what essentially was an extended pilot over three episodes with an arc storyline (another first!), Julia was hired to work in a high-end medical office in the aerospace industry. She and supervising nurse was Hannah Yarby, played by Lurene Tuttle, were managed by Lloyd Nolan's crusty-minded but soft-hearted Dr. Mortan Chegley.

Like the Waggedorns, Julia's colleagues were Caucasian. Football star Fred Williamson, an African-American, would join the series in the third season as Julia's romantic interest, Steve Bruce.

Julia was the result of series creator Hal Kanter's desire to right the wrongs of his less-worthy previous TV depiction of African-Americans: CBS's Amos and Andy (1951–54), which actually began on NBC Radio (in 1928). The TV edition was canceled due to racist portrayals, and series leads Alvin Childress and Spencer Williams were devastated, financially, because of that decision.

But ending Amos and Andy was ultimately a noble choice that led to the eloquence of Julia.

As Kanter explained in an archived video interview with the Television Academy, Jack Valenti, longtime president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), had invited him in 1967 to a fundraising gala for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

There, NAACP group leader Roy Wilkins voiced his concerns over the lack of positive Black role models on and behind the scenes of both film and television.

Up until that point, Amos and Andy, and other series, such as ABC's The Beulah Show (1950–53), with which Kanter was also involved, and which began on the radio (CBS, 1945–54), had presented negative African-American stereotypes. Only The Nat King Cole Show, a musical variety series, was praised for in its dignified depiction of prominent Black performers.

Unfortunately, the Cole show suffered from a lack of sponsorship due to racist perceptions, forcing its host to end the series after just one season. "Madison Avenue is afraid of the dark," Cole declared to the press.

Adjustments needed to be made and, upon hearing Wilkins' words in 1967, Kanter wanted to help change the panorama, specifically on television. Because of his connection with Amos and Andy and Beulah, Kanter felt "partially responsible" for some of the negative Black images then prevalent on TV and at the movies.

And so, he decided to do a show about "a Black woman who was independent and...intelligent," with a "respectful" pilot script he titled, "Mama's Man." Several Black actresses of the day auditioned for the role but when Kanter noticed Carroll, he said, "That's Julia. None of the others came close."

The show's title, however, wasn't working for Carroll and her friends including actor/singer Harry Belafonte and writer James Baldwin, both distinguished and high-profile African-Americans. Carroll's publicist subsequently suggested calling the series, The Diahann Carroll Show. But Kanter rejected that idea. For him, the show was not about Carroll. "This is about a Black nurse and her little son," he said. "So, we settled for Julia."

In the process, history was made, not only for single African-American parents but for African-American children. "For the first time in television," Kanter explained, "American Black children had a role model: little Corey Baker. We got more fan mail and more thanks from Blacks and whites, who said, 'Thank you for putting a young man like that on television for us.' It was wonderful."

"That first year was absolutely great," Kanter continued. "We were accomplishing something. We all felt that we were really contributing to the mores of the society."

Carroll, who died of cancer on October 4, 2019, had been a trailblazer for decades. Born in the Bronx on July 17, 1935, she grew into a glamourous, talented multi-hyphenate performer with a remarkable career that began with musical theatre in the 1950s.

By 1962, she had become the first Black woman to win the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for her performance in No Strings. The show featured music and lyrics by Richard Rodgers, a book by Samuel Taylor, and co-starred Richard Kiley, who was white. Thus, it became the first Broadway production to involve an interracial romance.

Off-stage, Carroll was making headlines for the same reason. Three of her four husbands were Caucasian: music agent/producer Monty Kay, fashion designer Fred Glusman, and singer/actor Vic Damone. Only her third spouse, Robert DeLeon, editor of Jet Magazine, was African-American.

On camera, and beyond Julia, Carroll made several notable big and small screen appearances including the heralded 1974 feature film, Claudine (1974), and ABC's '80s mega-hit prime-time soap, Dynasty.

With Julia, however, Carroll made her most indelible impression, even though she was initially reticent about taking on the role. And while Kanter had claimed to be immediately dazzled by Carroll upon their first meeting, the actress remembered quite differently the events that led to her winning the role.

In her interview with the Television Academy, Carroll said she "ran away" from doing the show, and did not believe it would work. She saw it as "something that was going to relieve someone's conscience for a very short period of time," and thought, "Let them go elsewhere," and find another actress.

That's when then-NBC executive David Tebet stepped into the picture. Tebet, described by Carroll as "a very good friend and a smart man," perceived it as comical that she did not want to star in the series, if only because Kanter had agreed with her. "He doesn't feel you could do it," Tebet told Carroll. "But I think you can."

Carroll still wasn't interested, mostly from a geographical standpoint. She was living on the East Coast at the time, and told Tebet, "I'm not moving to California. I don't want to know anything about living in California. I need this place in my life that validates me constantly, and that's New York City."

But Tebet was tenacious. Six months later, he called her again and said, "I don't want any arguments from you. I want you to audition." From there, the conversation went like this:

Carroll: "Does the creator want me to do it?"

Tebet: "Absolutely not!"

Carroll: "Oh! Why? Why doesn't he want me?"

Tebet: "Because you're Las Vegas and Broadway theater and it's not the image he wants. He wants the housewives to feel comfortable with this character, Julia."

Caroll: "So, he doesn't feel that I can pull that off?"

Tebet: "No. He really doesn't."

Carroll was stunned, inspired, and motivated. Upon learning that "Hal was not exactly ecstatic" about meeting her, the actress was compelled to prove him wrong; to prove that she could play Julia.

Subsequently, she left her beloved New York behind and flew to California three days before she was scheduled to audition for Kanter. Upon receipt of the Julia pilot script, she "worked on every line," with her makeup-man, hairstylist, and assistant, all of whom she brought along from Manhattan.

Determined and on a mission, she and her team purchased all available female-geared magazines at a local grocery store, insuring she was outfitted with the latest wardrobe and hairstyle. "That's what it's all about," Carroll recalled of her audition strategy. "Preparation, preparation, preparation."

After 36 hours of groundwork, the foundation was set in stone for what became Carroll's monumental arrival in Kanter's office. Almost immediately, Kanter turned to her agent and said, "That young lady that just came through the door. If Diahann Carroll looked like that, I could understand it."

As Carroll then told the Academy, her agent replied, "Thank God! That is Diahann!"

And with that, she went on to star in Julia, which began filming at 20th Century Fox studios.

"Everyone was on the line," she said, "and everyone was scared." This was a series about "a very upper-middle-class Black woman raising her child, and her major concentration will not be about suffering in the ghetto." All associated with the series wanted it to succeed, knowing they took a chance on "a different point of view about Blacks in the United States," Carroll observed.

But Julia had its detractors. More than a few African-Americans were "incensed" by the series, Carroll said. "The suffering was much too acute for us to be so trivial, they felt, as to present a middle-class woman who is dealing with the business of being a nurse in this huge, very successful [aerospace industry]."

The lack of a positive Black male presence was also a concern, which was eventually rectified when Fred Williamson joined the show. Up until that point, there was no then-traditionally masculine or father-image for children of any ethnic backgrounds to relate to. "That was a very loud criticism," recalled Carroll, who was confounded by but also empathetic to the protests.

"We were of the opinion that what we were doing was important," she said. "And we never, never, never varied from that point of view. Even though some of the criticism, of course, was vali, .we were of a mind that [Julia] was a different show. We were allowed to have this show. We were allowed to put this point of view on the air. We were allowed to have a comedy about a Black middle-class family.

"Television was going to have the kind of scope in time that would allow the ghetto situation, the middle-class situation, the upper-middle-class situation. Hal and I were [in agreement] about that. So, while the criticism was heavy, and sometimes, very unkind, sometimes threatening, we stuck with that premise."

Additionally, the showrunners hired African-American psychiatrists to help guide the production, with specific regard to Copage's Corey Baker and Link's Earl J. Waggedorn roles. The series also sought to involve the younger characters "in situations that made them aware of Black males," Carroll recalled.

"Mother dated and we brought the male into the house to say hello to the son. And, usually, it was another professional Black that [Corey] was exposed to."

Other complaints about the show had to do with Julia Baker's living space and wardrobe, both of which were considered too upscale for the mainstream Black experience. "You can't believe [the response we received]", said a flabbergasted Carroll. "People wrote columns. How could she live in THAT apartment? And where did she get those clothes?"

In response to those concerns, Carroll exclaimed, "It's television! We're not doing a documentary. You have to change that thought. I said, 'Where does Marlo Thomas get those clothes [on That Girl]? She's an out-of-work actress.' We began to say, 'You must stop believing that the only thing that is valid for Blacks on television is a documentary. We're doing a comedy! Let us do a comedy.'"

The criticism gradually permeated every aspect of the series to such a shocking degree that Carroll's life and property were threatened. One viewer "was going to hang me and burn my home," she said. Another time, she recalled being labeled "a terrible sellout!"

The attempt to present a positive, female African-American image on TV backfired and, according to Copage, the insults turned to injury, leaving Carroll on the "verge of having a nervous breakdown."

"Diahann was getting all kinds of pressure," he said, a result of those who claimed, "that the show was not Black enough."

But on the Julia set, Carroll "got along with everybody," Copage said. "I don't remember any kind of diva drama thing going on." Each time he observed Carroll's interaction with fans of the show, "she was always gracious," even to the younger admirers that might not have fully comprehended her celebrity status and talent. "She was just a wonderful person. Very professional," Copage said.

The actress was also straightforward, honest, and did not pull any punches. "Diahann would let you know if she thought things were not right," Copage recalled. "She wasn't weak or shy. Maybe some people might call that, diva-ness. But it's not really. When you're a [star] like that, you get to take control of situations. At the end of the day, it's your name that is associated with the show."

In another trailblazing category, Carroll was the first Black female to hold partial ownership of a television series, retaining 25 percent of Julia. The remaining amount, as Copage remembered it, was divided between Kanter, 20th Century Fox, and NBC. Although, "over the years, maybe someone bought out someone else," he surmised.

Working on Julia proved to be a particularly unique life and work experience for Copage. Off-screen, he was a child of divorce, raised by a single father. But in what he referred to as his "make-believe life," he was a young child being raised by a single mother.

In the process, Copage and Carroll bonded. As she explained in her memoir, Diahann: An Autobiography, published in 2008, Copage viewed the actress as his off-stage mother. "I would spend the night at her house," he recalled, much to the dismay of Carroll's daughter, Suzanne Kay. "She did not like that," Copage said.

While attending school, Kay's fellow students would inquire about Copage, "thinking that I was her real brother," he said. "At some point, it got to be so much for Suzanne, who complained to her mother about it, and maybe justifiably so. I guess if Diahann were my real mother, I probably wouldn't want to share her, either."

The personal relationship between Copage and Carroll subsequently suffered and was "cut off," he said. "And that was a bit traumatic."

Copage also acknowledged that his father and Carroll did not always "see eye to eye," which further widened the communication gap between the actors after Julia ended. Had the former co-stars remained in more consistent contact, Copage explained, "That would have been great. She would have been a great mentor."

Meanwhile, for Copage, learning of Julia's cancelation "was a shock."

Not informed of the details, he assumed the show would resume filming in the summer of 1971, following the third season's hiatus. Instead, his father told him that the show would not be returning for a fourth year. According to Copage, the formal press announcement stated that "Diahann and Hal wanted to pursue other endeavors. But I think the reality was that the stress was just too much for Diahann."

Fortunately, the former on-screen mother-and-son team periodically connected through the years, once, not too long before Carroll's demise. "We enjoyed a nice dinner together," recalled Copage. It was for a Julia reunion at The Hollywood Show [an autograph show in Los Angeles] that Copage reunited with his past-TV-parent, along with his retro-TV-best-friend Michael Link.

"It was just kind of a surreal feeling," Link said of the catch-up encounter at which Carroll was "gracious and beautiful." Reuniting with the show's co-stars ignited flashbacks. Link, who is a successful businessman today, recalled particularly mesmerizing and melodic memories of Carroll on the Julia set.

In looking back, he recalled periodically hearing "this voice" between filming. Each time he would turn his head, and ask, "What's that?" And it would be Carroll "out of nowhere, bursting into song. It was just amazing," he said.

Other recollections flowed of cherished behind-the-scenes moments, specifically surrounding the three-part, third-season adventures filmed on location in Las Vegas, titled: "Little Boys Lost," "Alter Ego," and "Tanks, Again."

Favorite episodes for both Link and Copage, these segments featured guest-stars Gary Crosby, son of Bing Crosby, Robert Alda (father of Alan Alda), and Cleavon Little, just three years before his breakout role in the now-classic feature film, Blazing Saddles (which ignited African-American-related controversies of its own).

"Both of those guys were just riots to be around," said Copage who described subsequent dune buggy rides with the actors in the desert as "a blast." The Vegas episodes also allowed for Copage's first visit to a casino where, as he mused, "I got quite an eyeful of some scantily clad ladies."

Link fondly recalled filming scenes at the pool with Alda, and another involving Copage, Carroll, and Betty Beaird, his TV mom. "We were in a convertible and we stopped at a gas station in the middle of nowhere." Corey and the young Earl J. Waggedorn were supposed to be asleep in the back seat. "But we woke up and went to the bathroom," Link said, "and we locked ourselves in."

Another of Link's favorite scenes from the show occurs in the pilot, in which Corey gets in trouble, and Earl J. wonders if Julia is going to spank Corey. When she replies, "Maybe," Earl J. says, "If you do, can I watch?"

"All these years later," Link said this vision still brings a smile to his face. "I am laughing now."

It's the less-complicated, innocent moments and plotlines that granted Julia its enduring charm, especially during the show's original run. "There's so many different shows to watch on TV today," said Link. "Back then there were just three networks to choose from."

Julia's lasting and on-going success is also a result of the natural charm of its cast, which blossomed in an atmosphere of support provided by a nurturing Kanter. "He always had a twinkle in his eye," Link recalled. "He made us all feel really comfortable."

When Link first auditioned for the show, impromptu, he placed a Chiquita banana sticker on his nose. It was a creative choice that dazzled Kanter and earned Link the job. His chemistry with Copage also contributed to that victory. "We seemed to click," he said.

The same could be said for the interactions between Lloyd Nolan and Lorene Tuttle, each of whom, as Copage recalled, were a "class act" and "terrific."

Clearly, if not always smoothly, Julia made an impact. Echoing Carroll's commentary, Copage said, the show became "important to a lot of people."

The actor/musician, who is preparing his memoirs, has for decades experienced first-hand the after-effects of being associated with the series. Many from his generation and beyond were raised by single parents of all genders who were drawn to the show just for that reason.

"Julia had a job that television did not portray Black women as having. Up until then, the majority of Black females on screen were maids and nannies" who cared for the children of Caucasian parents. "Diahann was the first to star in her own show in which a Black female was portrayed as something other than a domestic servant."

Carroll said that both she and Kanter were "very proud" of Julia. "It represented a new thought," despite the criticism the show received from those who Carroll described as "more narrow-minded and less visionary than Hal."

"So, I think we came out all right," she concluded.

Herbie J Pilato, host of Then Again, a classic TV talk show streaming on Amazon Prime, is the author of several books about TV including Glamour, Gidgets and the Girl Next Door, which includes a biography of Diahann Carroll.