When Downton Abbey debuted on British television in late 2010, it had all the trappings of another lavish Brit period literary adaptation.

But there was one crucial difference: it was not a literary adaptation.

Downton Abbey, a show about an English country house and its inhabitants, both servants and masters, was an original fiction set in 1912. The Crawley family and its staff were all inventions of writer Julian Fellowes. That gave him license to take the characters and storylines wherever he wanted.

Fellowes was well schooled in the vagaries of British society — a lord himself, he knew all about Britain's aristocratic history, punctilios and class divisions. But he was also a fan of American series like Friends, ER and NYPD Blue. He loved their narrative energy, masses of interlocking storylines and contrapuntal conversations in corridors.

He resolved to treat all the characters in this country house with equal weight, detail and dramatic impetus. Upstairs and downstairs, everybody would have a story of their own at least every three episodes.

The roles of Lord Robert Grantham (Hugh Bonneville) and his valet, John Bates (Brendan Coyle), were given to actors of similar gravitas. The romance of Mary and Matthew (Michelle Dockery and Dan Stevens) was no more important than the ardor between Anna (Joanne Froggatt) and Bates. Dramatically speaking, upstairs and downstairs were both on the same floor.

And so Downton Abbey — a production of Carnival Film & Television, whose parent is NBCUniversal — turned out to be a very modern period drama, like a vintage car powered by a hybrid engine.

The show lured viewers in with its window dressing — the crenellated gothic castle, the exquisite costumes, the baroque diction, Dame Maggie Smith's poison-tipped one-liners — but it was the machine-tooled storytelling that kept them coming back.

And how. Downton Abbey's first season was the highest-rated show in the history of PBS, its U.S. broadcaster (in the U.K., it was seen on ITV). Each year thereafter, the Masterpiece production broke the network's record; the fourth-season premiere drew 10.2 million live viewers — 15.5 million including the Nielsen Live+7 numbers.

The show's appeal seemed to know no bounds. It soon went global, and to date it has aired in more than 100 territories. China in particular seems obsessed by the goings-on in an English country house in the post-Edwardian period.

During its six-season run, which ended this past February, Downton has so far won 12 Emmys and been nominated for a further 47 awards. To celebrate the show's conclusion, emmy's London correspondent, Benji Wilson, asked members of the cast and production team to reflect on their time at Downton.

IN THE BEGINNING

Gareth Neame (executive producer): I'd always been an admirer of Julian Fellowes's writing. Years back, long before I knew him, I saw Gosford Park, and I was incredibly impressed by the whole approach taken. I was being shown this world that I'd seen depicted so many times in British films and television, yet I suddenly thought, "This is the first time that I really believe this world."

Then, a few years later, I met up with Julian. We were collaborating on a project that didn't ever happen. We had a dinner one evening and I said, "Could I ever persuade you to go back to the territory of Gosford Park, but to spin it off as an episodic television series? To go to a country house and do it as a precinct drama, a la West Wing?"

Julian Fellowes (creator-writer-executive producer): It wasn't called Downton Abbey at that point. I had a great-grandfather who lived in a house called Charford Manor, and that was the original name. They thought that was too near Cranford [a successful BBC period drama].

But that great-grandfather had started something called the Downton Cultural College in Wiltshire, so I changed it to Downton Manor for a bit. Then it became Downton Park. But after Gosford Park, I felt I was turning into a park keeper.

I called it Abbey after another house I knew. There was a brief moment of panic that everyone would think it was about monks. We felt that if they saw one trailer, they would be reassured

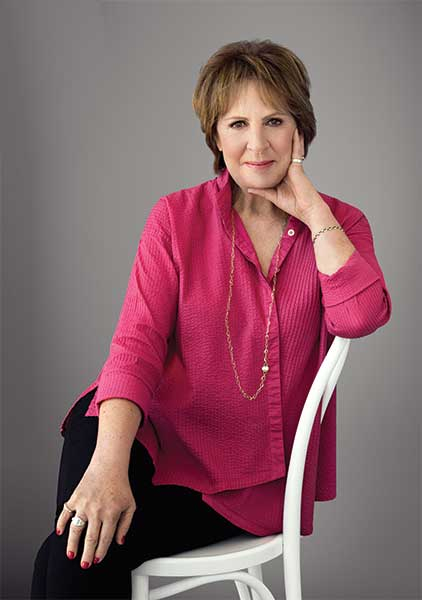

Liz Trubridge (executive producer): It was 2009.1 was working with Julian on a film, and he said he was going to see Gareth to talk about this new series he was doing. He said, "It's called Downton Abbey," and I said, "Ooh, tell me about it," and he did.

I thought, "Whoa! I want to do that." It was the notion of following one of those big country houses that have stood in their own parkland for generations and the lives of the people who lived in them — above and below. And to see them in a time of such social change, so you're straddling the wars, the end of the Edwardian aristocracy, and through the war and into a very different world.

The other thing that excited me was that it was close enough to our times to make it very accessible. People's grannies were around.

Neame: We took it to ITV in the U.K., and they said, "The last thing in the world we're looking for is Upstairs, Downstairs." But to give them their due, they were instantly receptive. It was the height of the advertising recession, and ITV was buying almost no new drama at all. It wasn't a cheap show for them, That was a very risky thing for them to commit to.

Fellowes: Everyone told Peter Fincham [then director of television at ITV] that he was mad, that there was no audience for this kind of thing. But he had real courage. It's great that they were so well rewarded.

Jim Carter (Mr. Carson): We were shown three scripts. You wanted to read them; they were page-turners. They've all been published now, and you'll see the stage directions are brilliant. We were asked to make a decision to commit to three seasons.

I thought, "This is worth doing," because of Julian Fellowes's background. And we knew that Maggie Smith was involved, which was her first time in an ongoing TV series. So it felt like it had gravitas and pedigree. I thought, "The butler? He's upstairs and downstairs — you can't do without him. He'll be a regular. Yeah, I'll sign up."

Elizabeth McGovern (Lady Cora): I was a huge fan of Gosford Park, and I'd also seen a movie [Fellowes] directed that I'd loved, so I was inclined to like the script. I read it and thought I was a shoo-in, because I was an American living in London! It took me a little bit of time to persuade everybody else....

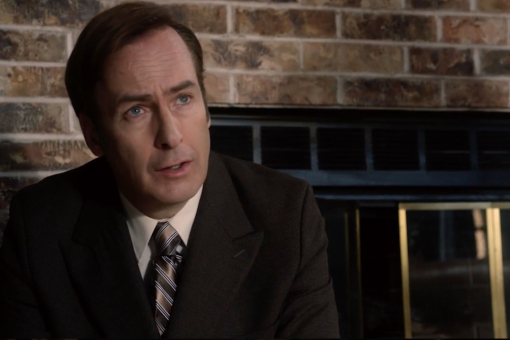

Hugh Bonneville (Robert, Earl of Grantham): I can still remember the first read-through and thinking it was a rather remarkable thing. It was so beautifully cast; I thought that every character felt true to life and true to the actor playing them.

Then I remember filming the garden party sequence at the end of the first season, when war is announced. We shot that sequence over two or three days, and the weather was so kind to us.

I remember standing out on the lawn with Maggie in these costumes with this beautiful, clear blue sky, and there were no vapor trails, not the echo of a plane anywhere. I remember her saying, "This is what it must have been like" — and suddenly I was transported back a century.

EARLY RATINGS AND AWARDS

Neame: The ratings for the first episode in the U.K. were very strong. But what happens normally in television is, a lot of people come and try the first episode, and then there's inevitably a drop-off. What you never see is 20 percent growth from episode one to two. I knew that was a sign of a very extraordinary trend

Fellowes: The first season was the great adventure. We'd made this show. We thought it was good. We thought it would find an audience, but we didn't have any idea what was coming.

Gradually, as it went on showing, it picked up more and more and more of an audience. References to it started appearing in the newspapers. On [long-running U.K. soap] Coronation Street, or whatever, someone would be talking about Downton Abbey. That was a rather extraordinary moment — to realize you'd written a show that was reaching the parts that other shows don't reach was very, very exciting.

Michelle Dockery (Lady Mary): The day after the BAFTA [Awards in early 2011] was such a massive memory for me. We'd had about an hour's sleep — we were all still half-drunk from the night before — and Jessica Brown Findlay [Lady Sybil] turned up in her BAFTA dress because she couldn't reach the zip to get it off.

We were all sort of bouncing around, still on cloud nine from the night before, because it was our first big event, really. It was the first time that the show had caught fire, and we were just in this kind of dream — all part of this massive thing, yet still so new to it all.

COMING TO AMERICA

PBS was known, in the words of one commentator, as "the channel that was always on in the background when you went to visit your grandparents." Downton revitalized the old faithful, and suddenly its actors found themselves on U.S. talk shows and red carpets.

McGovern: In the first year, when I was the American wheeled out to represent the show, I bravely went onto a talk show. They were asking about my show about monks in Greenwich Village starring Judi Dench, because they called it "Downtown Abbey."

Neame: It was awards success in America that really drove that message. The first season was nominated for many Emmys in the summer of 2011, but very few people had seen the show. Many of us were there [at the ceremony], and Brian Percival won for directing, Julian won for writing.... That drove people to the show. Six months later, everyone knew what it was.

Carter: We knew we weren't in Kansas anymore when the third season came out in America. The British ambassador invited us to his residence in Washington. He thanked us for making his job easier, because Downton sold the idea of Britain abroad.

Then, at 10 o'clock at night, we were whisked into blacked-out cars and taken for a private tour of the White House — because it was Michelle Obama's favorite program. We had Marines saluting us!

LADY'S MAID'S MAN

Fans became obsessed with Mr. Bates, the Earl's strong, taciturn valet, and his romance with the demure lady's maid, Anna.

Brendan Coyle (Mr. Bates): People started saying they loved the character after the first season. Then they started to really love the gentle, delicate romance between Anna and Bates.

Then I started getting letters from Alaska and New Zealand, and it just started to grow. Then, in season three, when there was a "Free Bates" march in San Francisco, I knew that something really was happening. I think it's because he's put upon, always struggling, that he has universal appeal,

HISTORY OR BUNK?

Downton Abbey was a fiction, but its appeal derived in part from how it regularly wove in real-life characters and historical events.

Fellowes: All you're trying to do when you use history in a drama is to say, "Look, this really happened." The way history is taught, sometimes it's as if history happened to this group of robots — and then real people started in 1968. That isn't the case.

So I would say that my brief was to make some references to things that were happening at that time, and then hopefully people went on to Wikipedia or Google and looked up the Irish Troubles, or [the battles of] Ypres or the Somme, and they learned something.

But I don't think that's my job. My job is to make them aware of the fact that history involved real people just like them, and they were getting through their troubles like we're getting through ours. In the end, Downton is a family saga. It has been popular, because people are involved with the characters. You never want to lose touch with that,

ARRIVALS AND DEPARTURES

During the third season, with ratings at an all-time high, two of the series' favorite characters, Lady Sybil and Mary's beau, Matthew Crawley, were abruptly killed off.

Dockery: The reaction was huge. But it was good, because it kept interest in the storyline — people wanted to know what Mary would do now. Sometimes I wonder where the storyline would have gone with Matthew and Mary had Dan [Stevens] decided to stay.

Fellowes: The only death that has ever been voluntary and invented by us was the death of William in the First World War. We just felt we couldn't let a household that size go through the War with no one dead when, in fact, death decimated households like this.

Other than that, the deaths came when the actors chose to leave. With the servants, they could go and get other jobs, but with members of the family, if we were never going to see them again, they had to die. So with both Jess and Dan that was forced on us.

Dockery: It was strange at first, filming season four. We'd all grown very close, and it was very strange not having Jess there. She's got a very distinctive laugh, and I remember thinking, "I haven't heard that in a while." And as [we played] sisters, we were good friends.

The same with Dan: I loved playing out that storyline. Matthew and Mary were characters that the audience had really invested in. So in the beginning it was really odd not having Dan around. But I guess the thing about acting is that you're constantly moving on.

A VIOLATION

Early in the fourth season, Anna Bates is raped by a visiting footman. The scene caused outrage among fans who felt that it violated the spirit of the show.

Fellowes: There was, as you can imagine, a lot of discussion about it. The point about Downton is that terrible things happened, but we didn't really dwell on them on screen — what we were interested in was how decent people dealt with those terrible things and the effects on their lives.

So the rape was not as garishly portrayed as it would've been in some shows. In fact, you didn't see it, but nevertheless it remained a big storyline for us. On the whole, I think we were right to go ahead but, as you can imagine, there was a certain nervousness as to whether the Downton audience could take it. I'm happy to tell you they could

Bonneville: What Julian and Gareth have been very astute about is allowing Downton to develop and breathe while being recognizably the same. It's like any show — you want to feel you know where you are — yet they have taken risks. People thought they had the measure of it, and then you had the attack on Anna, which completely changed the rules.

GUEST STARS

As Downton's international popularity grew, several high-profile stars made guest appearances.

Bonneville: We had Dame Kiri Te Kanawa flexing her tonsils in the fourth season, and Paul Giamatti, and of course Shirley MacLaine came over to star in the third-season finale. I was there in the hall when Maggie [Smith] and Shirley met for the first time. It was like Stanley meeting Livingstone.

In the dinner scenes, sitting between Maggie and Shirley and listening to some of their stories, I felt like I'd died and gone to heaven. The Apartment is one of my favorite films, and to be able to quiz Shirley about Billy Wilder and Jack Lemmon and the way they shot it was fascinating.

Fellowes: We have always had a bit of that — big Hollywood actors saying, "Can I come and work?" You had to ration it: the thing about guest stars is, they bring so much baggage that they rather dilute the Downton-ness of the whole thing.

BEST MOMENTS

Allen Leech (Tom Branson): Definitely the falling in love of Sybil and Branson in season two. That whole season — Sybil and Branson in the garage, falling for each other — was a really incredible time for me, and it was also an incredible time for us as a cast. The show had just taken off and was starting to have this life of its own, and it's never really stopped

Coyle: One of my favorite scenes was with Hugh in the first season when he tells me, "It's no good. It hasn't worked out, and you have to leave." It was very powerful.

And then, of course, so many scenes with Joanne. There was one quite early on where I knock on the door where the ladies' servants' quarters are and hand her a tray with tea and a sandwich on it, just to see if she wants it.

We did one version with some dialogue and one without any dialogue at all. We transmitted the one without dialogue, and it went viral. Viewers went mad for it because it was so tender.

McGovern: I enjoyed the whole storyline with Richard E. Grant [as the flirtatious art expert, Simon Bricker], because that was Cora telling us about her past. I loved exploring Cora's life outside of her role as wife and mother.

Trubridge: I have so many fond memories, but there is one moment: it was the first-ever Christmas episode we did, where lain Glen's character [Sir Richard Carlisle, who is briefly Lady Mary's fiance] says to Violet [Maggie Smith], "Goodbye, I'm leaving tomorrow and I doubt our paths will cross again," and she says, "Oh. Promise?"

Applause broke out on the set. It makes me smile every time I think about it.

Penelope Wilton (Isobel Crawley): I can tell you the worst moments, which are the dinner and lunch parties where they took ages to film. As you sat there, the food in front of you got less appetizing as the day went on!

I did love all my scenes with Maggie [Smith]. That's been a lovely relationship that Julian [Fellowes] has built up over the years.

The Final Season

Fellowes: Sometime around the third or fourth season, we knew we were going to finish it, so I'd had it in mind since then. I think you want to leave a party while people are still sorry to see you go, rather than waiting for them to be thrilled that you're leaving.

The young actors particularly want to feel free. In a way, the show's made them all stars, and now they need to take that stardom out into the market and see if they can find a career to support it.

Of course, in a way, I'm sad. This has been an extraordinary adventure and one that is very, very unlikely to be equaled in the rest of my life. But I've never thought we were wrong to bring it to an end.

McGovern: I feel it's the right decision. It really gave this last season a lot of depth and energy, because there's this thing that's going on underneath every storyline, which is that the way of life is truly slipping through their fingers. It's also been a way of life for all of us who have worked on it for this long. I think I was in one of the very first scenes we ever shot, Maggie Smith and I, so it's especially poignant.

Neame: Romantic love plays a big part in Downton — indeed, a much bigger and more significant role than I expected when we first embarked on it, In stories of romantic love, you need to have resolution, and so we decided to leave most things wrapped up rather than just cutting to black. The point is, we are moving the camera away and on to other things — but their lives continue.

LEGACY

Neame: I don't think it is overstating it to say that Downton has taken a much-loved British genre — mainstream historical drama — and given it a complete overhaul for the 21st century.

From a commercial point of view, it has proved that a British show can have the same reach globally as the biggest and best American shows. And the final piece of all this is that the show has waved the flag for British culture, tourism and exports in a way that goes beyond just a television program.

Trubridge: One of the things that Downton has done is explode the myth that period drama has to be highbrow or literary. I would like to think it would open the way for people to do more and more large-scale, cracking good stories.

You can do it in a different way, of course, but what people liked about Downton, I was always told, was that a) there's a large cast giving you lots of characters to like or hate; b) there are beautiful costumes, lovely sets and scenery; and c) there are stories that — in spite of being set nearly 100 years ago — are so relevant now.

It's the same old, same old: history repeating itself. There is something quite comforting about that — seeing characters you've come to love going through the same crap that you are.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ELISABETH CAREN L0VEARTISTSAGENCY.COM