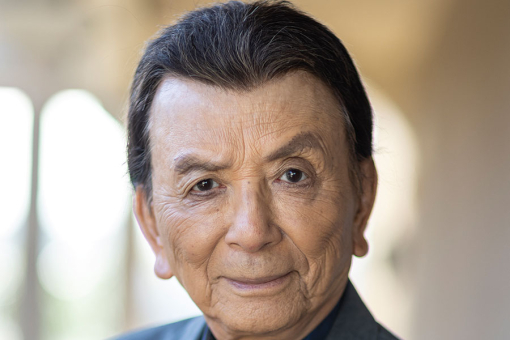

When television journalist Soledad O'Brien was passed over for an anchor position at a local station — because the outlet wanted to limit the number of woman anchors — she decided to resign. Later in her career, when she was again treated unfairly, she quit. "When your bosses don't believe in what you can accomplish, it's good to just leave," she says. "So I left and started a production company."

O'Brien's career highlights include a twelve-year stint at NBC News starting in 1991; she was a coanchor of Weekend Today and also a correspondent, filing reports for Today and The NBC Nightly News. In 2003 she moved to CNN, where over the next decade she anchored various news shows and launched the Black in America and Latino in America docuseries.

As CEO of her own company, Soledad O'Brien Productions, she has made documentaries such as Kids Behind Bars and Heroin USA for Al Jazeera America. Recently, she executive-produced the BET series Disrupt & Dismantle with Soledad O'Brien and this fall she'll bring a full-length documentary, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, to Peacock.

Over the years, O'Brien has been widely honored; her awards include three News & Documentary Emmys (for CNN's Kids on Race, plus coverage of the 2010 Haiti earthquake and the 2012 presidential election) as well as

two Peabody Awards (for her CNN coverage of Hurricane Katrina and the 2010 BP oil spill). A mother of four, she is also the author of two books: her memoir, The Next Big Story, and Latino in America.

O'Brien was interviewed in January 2022 by Jenni Matz, director of The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: You grew up on Long Island in the '60s and '70s with five siblings. What was that like?

A: Long Island was great in a lot of ways. But my mom was Afro-Cuban, my dad was white and Australian, so we were a mixed-race family in a not very diverse environment. In the mid-'80s I left for Harvard University, which was eye-opening. It was much more diverse, and in a lot of ways much more interesting than the little town I grew up in.

Q: You didn't study journalism in college. What did you study?

A: Harvard doesn't have a journalism department. I studied English and American literature. I was pre-med as well — I mention it because it was quite helpful for me in getting my very first job in television news. I worked with a medical reporter at WBZ-TV in Boston.

Q: What made you decide to leave Harvard?

A: I had been working toward being pre-med. And then I took organic chemistry with my sister who, to this day, is a surgeon. And I was like, "I'm not particularly passionate about this," which she actually helped me figure out.

I didn't want to go to med school. So I left to start working at an internship at WBZ, on a Spanish-language show called Centro. And then I was hired to work with the station's medical reporter. Eventually I would go back to finish my degree, but not till I went to NBC — I was working weekends and that freed me up to do the coursework during the week.

Q: Did you have an interest in being on camera?

A: What I thought was helpful about being on camera was, it gave you a lot more control. The people who were on camera got to dictate how the story went.

Q: How did you come to work for NBC Nightly News?

A: I started working for Bob Bazell in 1990–91. He was NBC's medical and science reporter, and he invited me to apply to work with him at NBC News. I learned a ton. By then, I was an associate producer and sometimes a field producer.

It was the start of my life of living on the road, which is just crazy and super busy, and sometimes really, really hard.

Q: Then you crossed the country to work for KRON....

A: Yes, NBC helped me get the job at KRON [the NBC affiliate in San Francisco until 2001]. I came in as the lowest level reporter, but I loved it.

Q: Did you face bias or discrimination at that time?

A: Those are always tricky questions, because how would you know? I certainly faced a number of ignorant comments. In Boston I would finish the morning show, stop in the bathroom, then run in late to the morning meeting. This guy would always say, "Oh, you're running on colored people's time." Is that bias and discrimination? Or is that just some colleague who's an idiot? I think it's the latter. It's just hard to know.

At KRON, when I wanted to learn to anchor, my bosses felt like they had too many female anchors. They didn't want any more. So they said no. I guess that's discrimination against more women anchors. It made it very clear for me that I didn't want to stay there. That's been my mantra: the minute people put up limitations like, "We feel you've tapped out here," and you don't think you have, you need to start looking for a new job.

So in '96 when my contract was up, MSNBC was starting and they were looking for an anchor for a show about technology [The Site]. I jumped to that show. It wasn't live, but it was a good anchor opportunity.

The Site didn't stay on the air very long, but it was really fun. And once you start anchoring, then you become a leader. I think that was the job where I first realized, "I actually have a big say in how this is going to go."

Q: And your next role at MSNBC was at Morning Blend?

A: MSNBC canceled The Site, so I went back to New York and started the weekend show Morning Blend, classic two-hour-long cable news.

I also started working during the week at NBC News. Eventually Today was looking for an anchor, and I was able to move into being the news reader on Weekend Today. [O'Brien went on to coanchor the show.]

Q: So why did you leave NBC?

A: I knew that CNN would present a much bigger challenge. I was doing about three hours of air a week on Weekend Today. At CNN, I'd be doing three-hour shows five days a week [as a coanchor of American Morning]. I felt like it was going to be a real learning experience."

Q: Less than two years later, in 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans and you went to cover the aftermath. What was that like?

A: It was very chaotic, because there were no basic necessities. We didn't have hotel rooms; we didn't really have showers. Normally you get in, you dump your stuff and set up your workspace. There was none of that. The cell phone towers were down, so we had satellite phones. There was not really any food, so CNN set up meal service. At the end of every day, you'd have to get rid of your shoes, because you had been in such deep muck filled with oil and other disgusting stuff.

So many people had left, and the city was kind of empty and abandoned. But the people who were still there were trying to figure out how to make their way. And the reason my coverage of Katrina was so good was because my executive producer, Kim Bondy, was from New Orleans and knew that place like the back of her hand.

Q: What's your strategy for an interview like the one you did with FEMA director Michael Brown, asking tough questions that he wasn't prepared to answer?

A: That actually happens a lot. Government officials often get so far by bullshitting people. If you're really listening to what they're saying, you can call them on their bullshit. You can tell them that this is not accurate. It was a really good example of the value of just listening in an interview.

He needed someone to say, "How are you possibly bragging about this? Are you telling me this is good?" Sometimes that's missing today in political reporting — nobody goes for the real question that needs to be asked. What he was saying was indefensible and inaccurate. And he'd been getting away with it. We were well aware of what was happening there. And we wouldn't let him get away with it.

Q: In your book, you wrote about leaving Louisiana and the reaction you received.

A: We had been there for two, maybe three weeks. And I remember walking through the Baton Rouge Airport, because you couldn't fly out of the New Orleans Airport. We had CNN caps on, and we got a standing ovation. I think it was because we did a good job. We were bringing an important story to America and to the world. It was one of the few times that I felt, as a journalist, this is what we're supposed to be doing. We're supposed to be informing people. We're supposed to be pushing back hard on bullshit. We're supposed to be elevating the voices of people who don't have an opportunity to tell their story. That's our job.

Q: Shifting gears, in 2007 you left the anchor desk at American Morning and moved to the documentary division at CNN. What prompted that?

A: My boss just said, "We want to move you into documentaries." I had done a couple, and I think they'd gone pretty well. I enjoyed it. I thought that if I was going to be doing this, I'm not going to just show up and read what you put in front of me.

That was probably the biggest challenge in that new job. At the time, people would come in and say, "Here's the story we're doing." And I'd say, "Well, actually, that's not the story I want to do. We need to rethink this."

Q: Your first project was Eyewitness to Murder...

A: Yeah, it was a Black in America documentary that looked at the life and death of Dr. Martin Luther King. And the next two, two-hour chunks looked at the Black experience in America. It was conceived as a six-hour series, and it did so well that the network decided to keep doing it. We ended up doing it over nine years.

Q: You've talked a bit about asset framing and deficit framing and how they influence the way stories are told...

A: A friend of mine opened my eyes to that. One way of deficit framing is to think of "poverty porn," showing pictures of impoverished people but not understanding them. I want to understand people's motivations and why they do what they do.

I remember getting into a big argument with one of my producers. We were doing a story on a young woman. The first pass of her script came back, and it said, "Her mother was a crack addict, and her father is an alcoholic." On the one hand, that was true. But imagine if I introduced you with a list of all the horrible things your parents did. You would be horrified. The story we were telling was of a lovely young woman who was trying to overcome the odds to get into college.

I remember thinking, you can deficit-frame — you can give people the list of everything working against them — or you can asset-frame. We all asset-frame our own children, right? I would say, "My daughter's so lovely, helpful and smart." That's how you talk about people you like.

Often in newsrooms, we tend to deficit-frame people. It's correlated by race and by class. Poor people, especially poor people of color, we deficit-frame them a lot. We'll say, "Little Janey Smith, her dad went to prison," versus how we would tell the story of a middle-class kid. We'd say, "He's wonderful and hard-working — he loves sports."

It became very apparent to me that deficit-framing was the way that we told stories in impoverished communities and of people of color all the time. So I just wouldn't do it.

Q: You left CNN in 2013. What prompted that?

A: A new president came in, and he did not want me to anchor my show anymore. He said it very clearly. He asked me to stay and asked if I would be more of a fill-in.

So again, back to the same way I felt when I worked in San Francisco. When your bosses don't believe in what you can accomplish, it's good to leave. So I left and I started a production company.

Q: What was your goal in forming your own company?

A: I wanted to do things that I wanted to do. To be able to say, "Here's who I want to work with; here are the stories I want to do," that was the big picture of starting the company. I knew that we had carved out a very good niche in under-reported, under-covered stories, and that we had a lot of leverage there.

We did a documentary series for HBO called Black and Missing, which is a look at Black women who've gone missing, the two women who run the Black and Missing Foundation, and why the media and law enforcement don't pay as much attention to people of color who are missing. [The series is a recipient of this year's Television Academy Honors, given to programs that spark social change.] Since I started my company, we've put together a very good team and we just keep creating projects.

Q: What are your thoughts on the role of journalists today?

A: Journalists have a duty to the audience and should be informing the public. They should be elevating what is accurate and truthful and be very careful not to elevate inaccuracies and lies. Journalists should hold people accountable, especially people in power. And journalists should be asking questions for those who don't have the political or economic clout to push for answers.

I don't think it's super-complicated. I've been very disappointed to see in some cases politics treated like a sport, which I think is a really bad way of looking at it. It's also an indication of people who don't necessarily share the worries and concerns of their audience — certain things don't matter to them, because they don't affect them.

Q: What has been your proudest professional achievement?

A: I don't really know the answer to that. Sometimes people will hear my résumé and say, "You worked at CNN?" As if my only job is being on Twitter or hosting Matter of Fact [a weekly political magazine syndicated by the Hearst Network]. I think I have an important voice — only in that I get to elevate other people's voices. And I think that's critical.

The contributing editor for Foundation Interviews is Adrienne Faillace.

To see the entire interview, go to: TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews

Read about Soledad O'Brien's Disrupt & Dismantle docuseries here.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #8, 2022.