Over a weekend, life as we know it was destroyed. A mutant fungus ravaged the world and transformed people into monstrous creatures that destroy, mindlessly and compulsively.

Everything about HBO's The Last of Us screams: not now! Why would anyone want to watch a series about a global pandemic far worse than the one we're experiencing? The drama's video-game origins could put off those who don't play, and fans of the game may be disillusioned after years of poor game adaptations.

"We want to make sure, especially for people that haven't played the game, there's no barrier to entry," says Craig Mazin, the series' cowriter and coexecutive producer. "We made the show for people who'd played it a hundred times or zero times. There are different kinds of immersion. When you're playing a game, you're moving around. You're shooting. On television, it's a passive experience. So the immersion becomes about never challenging your sense that this is real."

As someone who loves and respects the game, Mazin was determined to stay true to it. Besides, he adds, cowriter and coexecutive producer Neil Druckmann, who created it, would never allow any changes to its culture.

"Ultimately, I want to make something that people would watch and say, 'Well, this is beautiful,'" Mazin adds. "It's going to make me cry, and it's going to make me laugh. But in the end, I hope it's also thought-provoking. I want it to sit with people. I want it to be the kind of show that they need to talk about every week, and when it's over, take a moment or two to process what just happened. It's very similar to the goal I had when I made Chernobyl — to take the terrible circumstances and make something beautiful."

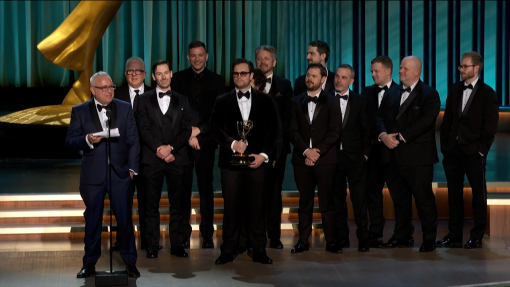

HBO's Chernobyl, about the 1986 nuclear disaster in Ukraine, won Emmys for Outstanding Writing for a Limited Series, Movie or Dramatic Special; for Outstanding Limited Series and for directing, among its many awards. This new series carries high expectations, given its built-in audience and a budget reportedly in the range of $10 million per episode.

The nine episodes deliver a complex story that, twenty years after that apocalyptic weekend, focuses on pockets of survivors cobbling together new lives in a desolate landscape.

When Druckmann conceived of this intricate world for the video-game company Naughty Dog (a division of Sony), it was strictly as a game.

"I was inspired by Ico," he recalls. "It's a somewhat obscure Japanese game that uses mechanics as a way to build a relationship between two characters. I've always been intrigued with that concept and trying to take it much further. Then I eventually got comfortable with the idea of exploring a story that's about making the player feel the unconditional love a parent feels for their child and the sacrifices a parent would make."

The game prompts viewers to consider if the individual — your individual — is more important than others. Will a parent sacrifice a child for the greater good? This unconditional love extends to relationships — even when they're not biological.

Game of Thrones actors Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey play the two main characters, Joel and Ellie. Battle-weary, Joel is on a mission to find his brother and protect Ellie. Just fourteen, she kills without flinching and has seen more than anyone ever should. But she's still a kid who loves goofy puns and is mesmerized when she sees giraffes for the first time. Plus, she's the only human who bears the deadly fungus's leaf-like scar and has survived.

Joel and Ellie's unlikely bond deepens as they cross the country. It's a grim journey through what had been civilization. Every system built by humans is gone or nonfunctional. The few survivors they encounter are vigilant, certain that whatever crosses their path will harm them. That fear is justified.

Another unlikely bond connects Bill (Nick Offerman, Parks and Recreation) and Frank (Murray Bartlett, The White Lotus). In a poignant episode, they find enduring love. It's a bit of a detour in the narrative, yet it remains true to this universe.

"That's the first time the series can take a bit of a break," Mazin explains. "The first episodes are the hardest because they have a billion jobs to do. Every other episode just gets to be what it wants to be. The first episode needs to teach you who these people are and what's going on in the world. What are the rules? What's the tone? How's this going to work? Introduce more characters and then drive to a conclusion that makes you want to come back next week because, thank God, we're on HBO and we are weekly, which is the way God intended."

The collaboration between the show's creators was born of mutual admiration. Mazin played The Last of Us, which has won critical acclaim, spawned a sequel and sold 37 million copies since its 2013 release. Druckmann was blown away by Chernobyl.

"The way he handled [Chernobyl] so deftly, I thought was just so captivating, despite the subject matter," Druckmann says. "I thought, 'Man, it would be cool to have someone with that kind of taste, who understood that tone so well, to work with on The Last of Us.' I had that inkling of a thought, but really, I wanted to meet with him to gush about Chernobyl.

"We met for lunch and I had a bunch of questions about what it was like to make it, how he came up with it and what it was like working with HBO," Druckmann continues. "Likewise, he had a bunch of questions about The Last of Us. And the way he was talking about it, I felt like he really got it. By the end of that lunch, I asked him kind of offhandedly, 'Let's say we wanted to do this as an HBO show. What would that process look like?' And he said, 'Oh, it'd be very easy because we're in Santa Monica, right across the street from HBO's offices. And we tell them we want that to be our project, and they say yes.'"

They began work just as Covid was surfacing. It seems a bizarre coincidence, but Mazin notes it wasn't "that crazy because the thing about the pandemic in the show is that it happened. In its own way, it's kind of over in the sense of like, we lost, and it's there permanently."

The outbreak in The Last of Us "is much worse, obviously, than anything we experienced with Covid," Druckmann says. "And most of the story is an exploration of a post-pandemic story. The pandemic is really just the first episode. Knowing that people are now more sophisticated and have a much greater understanding of outbreaks, we had to make sure our research was all there, everything we're doing to feel believable, so you can imagine yourself in that world, in that story."

Given the dystopian setting of the show, which has been renewed for a second season, the simpler route to series might have been animation. The science-fiction elements of the infected might seem suited to that medium, but it wasn't considered.

"The game already is animated. It's motion-capture, but it's animation, so there was no reason, in my mind, to replicate that," Mazin says. "But also, what I'm interested in is making a television show. There are things that you can do in animation that are incredible that are very difficult to do in live action. But there are things in live action that are easier to do than in animation, like emotion."

Some of the infected people look human, albeit decayed and with what resembles mushrooms growing out of their heads. That's from a mutated strain of cordyceps, a real-life fungus, explains Mazin, who earned a degree in neuropsychology from Princeton. Once cordyceps hijacks people, they don't need food as we know it and can draw nutrients from the ground. They exist, though it's more of a purgatory than a life.

Actors who pop up in different episodes include Melanie Lynskey (Yellowjackets) as a cold-blooded revolutionary leader and Graham Greene (Goliath) as someone who moved to the wilderness long ago. Rutina Wesley (Queen Sugar) plays Joel's sister-in-law, who leads a community rebuilding.

The human spirit as a phoenix reborn from ashes may be a convenient trope, but for Mazin and Druckmann, the show's driving emotion is love.

"So much of what it's about is an exploration of the other side of love," Mazin says. "We all understand the romantic, positive side, and we can see it in action whether it is Bill and Frank, or it's the paternal love that Joel has for his daughter, that Joel has for Ellie. But what are the things that love demands of us? And we pretty strongly imply that there's two ways to go here. One way is to make the world better around you. And one way is to preserve and protect the person you love by any means necessary, including terrible violence. Because love is the source of fear. Love is the source of tribalism. That love is the source of my child's life is worth more than one hundred of your children's lives. And that's the problem. That's what we really dig into."

As a new father, Druckmann felt these emotions deeply while creating the game. "I was thinking about everything my parents have done," he says. "I grew up in Israel and they've made all these sacrifices to protect me and my brother."

He relays a conversation he and his father once had about Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier who, after being held captive by Hamas for more than five years, was freed in a trade for 1,027 prisoners, most of them Arabs. Druckmann and his dad discussed whether the exchange was fair.

"He said, 'Are you asking me [to answer] as the prime minister of Israel or as Gilad's father?'" Druckmann recalls. "'As the prime minister, I would feel absolutely not, because he put Israel in a much weaker position. As the kid's father? Not enough! I would have traded way more to get my son back.' And I think there's no right or wrong answer here. It's just like, how small does a human get when we become stressed about the people that we care about?"

Devastation Simulation

The post-apocalyptic, dystopian world of The Last of Us — its ruined cities and highways, dank hotels and shops — feels surprisingly realistic. They may have originated in a computer game, but the show's intricate sets were hand-crafted.

"Everything that is desiccated is built," production designer John Paino says. "My biggest surprise was that there were no places just sitting rotting that we could use."

He was hoping for rot in Calgary, which stood in for great swaths of the United States. CGI was used only for action over twenty feet high.

Monsters burst through a newly built street surface thanks to a "blister" of weak material Paino's crew fabricated. Other sets included a water-logged hotel room and a childcare center. The crew made ninety-eight sets and kept the video game running on a loop in their office while working.

"The goal was to capture the atmosphere and the feeling of dread and the realism of the game," Paino says. He adds that the challenge was "to craft a world where most life stopped twenty years ago. The production needed to make buildings look decayed and to have the characters travel from Boston to the West. They needed specific foliage, none of which was growing in Calgary."

A couple of episodes used existing structures that were dressed for the show. That highway that looks so real had to be shut down, and then the crew added rusted vehicles to create an eternal traffic jam. That mall had been empty, about to be sold. Paino built an arcade and some typical early-2000s storefronts. Everything needed to look grimy.

"There's just never enough dirt," he says. —J.C

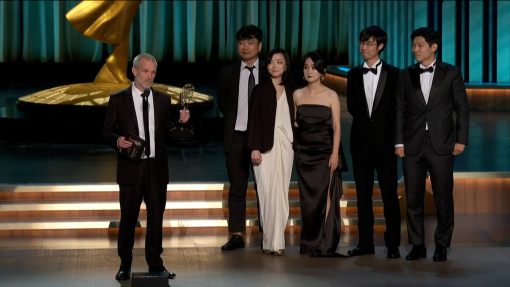

A coproduction with Sony Pictures Television, The Last of Us is executive-produced by Carolyn Strauss, Evan Wells, Asad Qizilbash, Carter Swan and Rose Lam. Production companies: PlayStation Productions, Word Games, The Mighty Mint and Naughty Dog.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #1, 2023.