In 1982, a Yale writing teacher named David Milch wrote a script for Hill Street Blues, a police procedural that Steven Bochco had cocreated the previous year. The script sold, and Milch joined the staff, where he soon became executive producer and began a celebrated career as a creator, writer and producer of TV dramas. He created four other series with Bochco. This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the premiere of their most successful collaboration, ABC's NYPD Blue. In its twelve-year run, that multifaceted drama about New York City homicide detectives won twenty Emmy Awards, two of which went to Milch for writing. (He'd won his first in 1983 on Hill Street Blues.)

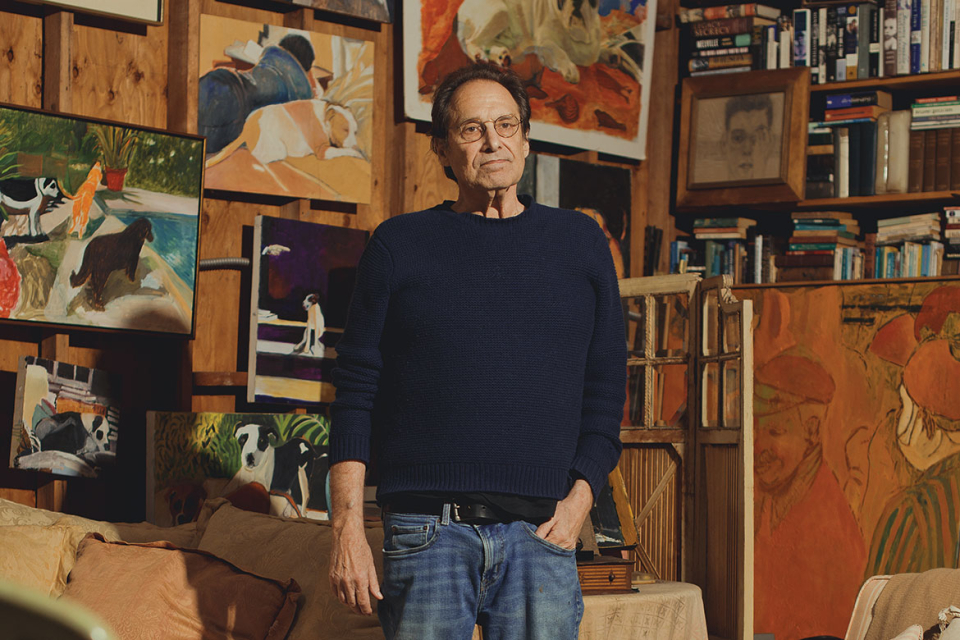

Much of the heat and raw material Milch drew upon stemmed from his own upbringing in Buffalo, New York. His father was a respected surgeon but also a prescription drug addict and compulsive gambler who took his own life in 1979. In his candid 2022 memoir, Life's Work (a collaboration with his editor-artist wife, Rita, and their writer daughters, Elizabeth and Olivia), Milch describes his own addictions to heroin, alcohol, prescription drugs and gambling — which he maintained while attaining enormous professional success. (He got clean from drugs in 1999.)

As an undergrad at Yale, Milch studied with writer and poet Robert Penn Warren, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning political novel All the King's Men. After graduating summa cum laude, Milch earned a Master of Fine Arts at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, then returned to Yale to teach writing and English literature.

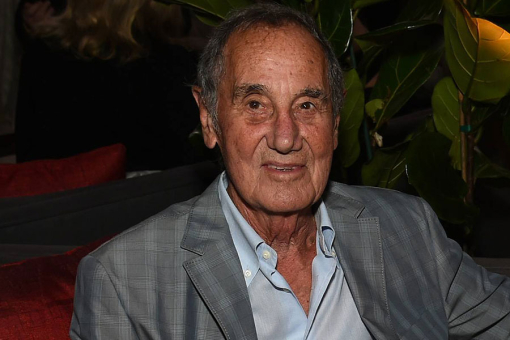

He was cowriting an anthology of American literature with Warren and others when a former roommate introduced him to Bochco. Hill Street Blues, which had been on NBC for about a year, focused on overworked cops at a fictional urban precinct. Innovative in its use of an ensemble cast, complex stories and inventive camerawork, the series ran from 1981 to '87 and won twenty-six Emmy Awards.

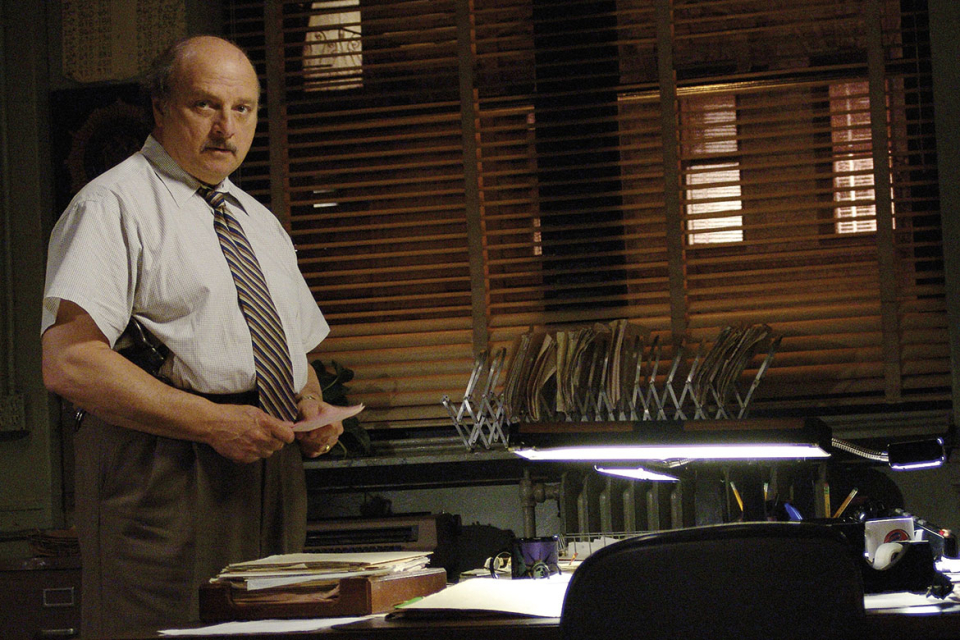

Next, Milch cocreated a spinoff, Beverly Hills Buntz, with Hill Street Blues writer and coexecutive producer Jeffrey Lewis. The dramedy starred Dennis Franz as Norman Buntz, a character he originated on Hill Street Blues, and ran in the 1987 season.

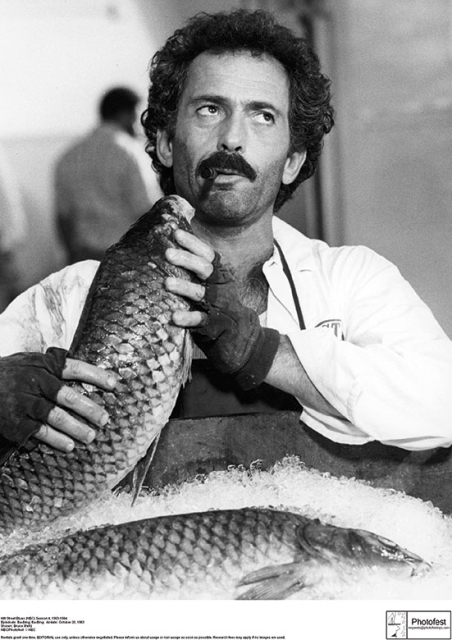

Then came NYPD Blue. For twelve years, this gritty procedural interwove the personal and work lives of a New York City homicide detective squad. Franz again starred, this time as Det. Andy Sipowicz, who struggled with alcohol addiction. The cast also featured Gordon Clapp, Kim Delaney, Sharon Lawrence and Nicholas Turturro. Initially, David Caruso played Det. John Kelly, but he left the series after season one. Jimmy Smits then joined the cast as Det. Bobby Simone. In language and nudity, the series pushed the limits of so-called decency and was even fined by the FCC, though an appeals court reversed the fine.

Following NYPD Blue, Milch cocreated two short-lived crime series: Brooklyn South (1997–98) with Bochco, Bill Clark and William M. Finkelstein, and Big Apple (2001) with Anthony Yerkovich.

Milch's finest work may be the intense, violent drama he created for HBO in 2004. He'd originally pitched a series about Christianity in ancient Rome, but HBO had a show about Rome in the works so they asked for a story set elsewhere. He came up with Deadwood, set at an illegal settlement in the Dakota Territory during the 1870s Gold Rush. Ian McShane starred as a pimp and saloon owner, and Timothy Olyphant as the sheriff, with actors playing real people of the era, like Calamity Jane and Wild Bill Hickok.

When Deadwood premiered, it made the biggest splash of Milch's career. Despite critical acclaim, the series ran just three seasons before HBO dropped it due to low ratings.

Milch's next project was John from Cincinnati, a surfing drama with paranormal elements, which he cocreated with novelist Kem Nunn. It aired on HBO in 2007.

In 2011, Milch created Luck, a show about horseracing that starred Dustin Hoffman. As he was writing the ill-fated show (HBO canceled it in season two after three horses died during production), his business managers hit him with shocking news: he owed millions in gambling debts plus $5 million in unpaid taxes, for a total of at least $17 million.

Milch's wife, Rita, established a payment plan with the IRS. They sold both their houses and moved into a rental in Santa Monica, and Milch was put on a forty-dollar-per-week cash allowance. A complaint was filed against his business managers, who settled out of court. To curtail his gambling compulsion, Milch started medication, which he still takes.

Long after Deadwood ended, Deadwood: The Movie began to take shape. In 2015, as Milch was writing the screenplay, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. In 2018, his longtime collaborator Bochco succumbed to leukemia. The Deadwood TV movie debuted in 2019, the year Milch moved into an assisted-living residence. He still lives in a memory care facility but is collaboratively writing a new TV series and works from an office at 20th Century Studios in Los Angeles.

Milch spoke to emmy contributor Jane Wollman Rusoff from his office, where he displayed a wry humor and without hesitation produced recollections of his years in TV, as well as a number of personal experiences. He did not share details about his current project.

Are you writing anything now?

Yes. I have health issues, as was predictable, given the way that I carried on. But those were the cards that were dealt.

Are you writing a new television series?

Yeah, I'm writing for television in collaboration with people and artists I respect.

Do you lie on the floor and dictate your scripts, as you used to? If so, how does that help you?

I still do. I was trying to get away from myself, in a way, trying to give myself to the dynamics that I was responding to and to become part of those, as opposed to allowing myself to be curtailed or shortened in some ways.

Did you have a tape recorder running to capture your thoughts and words from your position on the floor?

I had a tape recorder and someone who worked for me a good deal of the time helping with the logistics of my efforts.

In your memoir, you say that every day before you started to write, you prayed. It was a submission to shaping certain truths and acceptance of those as givens — not to be allowed to distort or pervert efforts that I had undertaken.

You used to read the Bible, so you said in your book. Do you still do that?

Yes, but I'm not assiduous about it.

How much did you use your own life and experiences as raw material for your stories and scripts?

So many of my experiences have shaped me past any alteration. I had decisions to make about what I would accept, and some truths are very unpleasant but nonetheless emphatically accepted. I've knocked around a good deal. Those experiences have shadowed and qualified — and in some cases distorted — the fundamentals of my profession. But I think that ship has sailed. It is what it is.

You had a chaotic childhood. Your father, a doctor, was an alcoholic, hooked on Demerol and liked to gamble at the track. Did you draw on that in your writing?

Yes. I drew on it in fundamental ways, accepting as governing certain dynamics and principles, not all of them pleasant. I used them in my writing. I had to. Those experiences shaped me. In many instances, they were irretrievable. The dynamics of my relations with my family settled a lot of questions early on. And just as early on I turned my back on the idea that things were going to be different.

You mean, that it was always going to be that way?

Yes. A lot of those truths were painful. I hope I've been sufficiently resilient in responding to those influences. I did my best to shape stories that I was telling according to the truths that were brought home to me.

What was challenging for you in the actual act of writing?

Everything. In my experience, the process of adaptation had to be made constructive. You're not going to subdue and distort the truths with which you disagree. You have to find a way to make that process of adaptation live.

On your best-known series, you usually didn't complete scripts until the very last minute. Did being under pressure help your process?

I think it did. It also required a kind of humility before shaping contradictory facts. That's the way the process works, or fails to.

It must have been rough on some of the actors.

Yeah. [Laughs] I say amen — to the reaction and resignation in many cases. There are certain walls you don't try to climb.

Even now?

Yes. There are new truths that you have to learn to deal with or reject, and in the rejection, change the content of what you're doing.

You mean in life or in writing?

In both.

Would you talk about working with Steven Bochco on Hill Street Blues and NYPD Blue?

He was such a protean, shaping presence and resilient in his capacity to adapt. Working with him, you had to understand how things were going to proceed. And if you weren't going to accept that, then there was no point in protracting the relationship.

You knew where you stood!

You knew where you had to stand! That capability to adapt was part of Steven's genius, to know how to work with and shape those influences. In some instances, Steven had to accept things that he didn't believe in but which he had to acknowledge as intractable presences. He found ways to do that, and that was part of his brilliance.

Tell me about working with Dennis Franz, who starred as Det. Andy Sipowicz on NYPD Blue.

Dennis was a genius. He was so responsive to the givens of the universe he was made to walk in, and he did it brilliantly. There was an exhilaration to working with him because he stayed alive to the truths that were controlling him, and he was resilient to the conditions that were shaping his behavior. He was magnificent.

Initially, he didn't want that role because he wasn't interested in portraying yet another cop.

Yup. And in a way, he found the path so that it was his character's personality rather than the absolutes of his profession. He knew how to work those and work around them a good deal.

How was working with David Caruso on NYPD Blue's first season?

He was a tough nut. He was brilliant in his resiliency. But it wasn't a dynamic that served me in a constructive fashion. He was going to work the way he was going to work, and that had to be understood before he walked in the door.

I imagine that made it difficult.

Yeah, it did. But you had to find a constructive response to your impulse to resist. You had to find a way around it. He was brilliant in what he chose to pursue. The pursuit itself didn't particularly engage me, but he was certainly a protean presence.

Let's talk about Hill Street Blues. Tell me about working with Daniel J. Travanti, who played Capt. Frank Furillo.

Travanti had a sensibility of tremendous depth. He was keenly aware of what was possible in performance and knew how to play those chords.

How about Bruce Weitz, who was Sgt. Mick Belker on the show?

We didn't particularly bring out the best in each other. I hope I was respectful of his points of view, many of which I didn't share.

Any thoughts about Veronica Hamel, who played Joyce Davenport on Hill Street Blues?

She was resilient. She was inventive and feminine in very instructive and inventive ways. And that was a privilege for me.

Over the years, did you have any big battles with networks?

Yes. You had to find ways to respond to Steven [Bochco]'s world view. And then to engage with that process with your response and find ways to make that constructive and inventive. He was a genius at that. He didn't have a deep, resounding truth that guided him, but there was ingenuity in the way he dealt with what were intractable obligations.

You write in your memoir that the collaborative process in the writers' room is a good thing. Why?

It's a big time-saver. But you've got to get resigned to the shaping that's being imposed. [That surrender comes] when you're driving home after the day's work is done [laughs] — to the extent that you're able to be constructive.

You also write that the trick as a writer is to "compress the layering of impressions so that the audience feels, 'Oh, there's more than one thing going on with this guy.'" Did you know that from the start or learn it through years of writing for TV?

I learned the tactics of resignation and acceptance, and the tactics of circumvention. And it kept you busy.

Did you routinely write many drafts?

I have a shaping heart. The deeper you go into your work the more you discover, and sometimes you get lost.

You wrote most of Deadwood in iambic pentameter. Was that difficult?

Yes. But Mr. Warren — [poet and novelist] Robert Penn Warren — was a master. I remember my first protracted exposure with him. I was a student of his, and he shaped me a good deal.

Did you learn how to write in iambic pentamer from him?

Yes. Adapting and reacting to his perspectives was an education unto itself and a privilege to participate in. You have to find a way to shape your experience with truth and grace, if possible. I tried. My relationship with Mr. Warren was fundamental to that dynamic. He was an extraordinary spirit and tough-minded. It was exhilarating to be able to work with him and to be of assistance to him. He was a great, great soul and a tremendous participant in the process of being useful, constructive and fully adapted, or adapted as well as one could find a way to proceed.

How was working with Ian McShane, who played Al Swearengen, the saloon owner on Deadwood?

He was terrific and qualified, by which I mean he was shaped by an adamancy of intention. And he backed his strategies brilliantly.

Timothy Olyphant played Sheriff Seth Bullock on the show. What comes to mind about him?

I had a lot of respect for him. He was realistic about the depth and extent of his gifts, and worked with those in a very constructive way. I understood that character in my experience with Tim much more than I had anticipated.

Had you planned to create a character with a disability on Deadwood? Or did you get that idea from your chance meeting in a pharmacy with Geri Jewell, who was born with cerebral palsy and would play Jewel on the show?

She came in and took the room.

What did you think of Deadwood: The Movie?

I thought it was respectable and had a resiliency in its depiction. I didn't feel any particular compulsion to react to it, simply because I had worked there before.

Would you have preferred doing another season of the series rather than a movie based on it?

Yes, I would.

What was the most fun you had on set doing your series?

There were people — one named Bill Clark [a consultant-turned-producer on NYPD Blue and other series] who comes to mind immediately. He had been an [NYPD] detective for twenty years, and he shared certain defects of character with me. We were deeply, deeply respectful and affectionate with each other. It was a privilege to work with Bill and be with him outside work. Bill was always inventive and instructive in responding to my situations. I had bad habits, and he found ways to allay some of the results of my foolishness. We've remained friends.

By bad habits, do you mean drugs and alcohol?

Yeah. And gambling — and don't stop there. There was a breadth to our misbehavior that was not absolutely qualified by our professional activities.

But you did so well professionally despite those habits. You didn't let them screw up your career, did you?

That's right. I'm obviously toward the end of my connection with that enterprise — the process of what I do. Not only in television. But television has been a vehicle for a lot of work that I've been able to do in other fields. I'm awfully glad and grateful to have been allowed to participate.

In 2011, when your business manager informed you that you were at least $17 million in debt, how were you able to cope with that shock and yet continue to write scripts?

Desperation is what comes to mind. I was a degenerate gambler, and I had other bad habits. I learned to walk on. There's no trick that I've been aware of to survive all this for a significant portion of time.

Did the "business" of television — pitching, negotiating, ratings, cost-cutting, firing people, pilot pickups — bother you much?

It's a living fact. I don't think we can change course. It would be too fundamental a rethinking to go to work on that problem.

In your memoir, you write that you'd ask your young kids to watch NYPD Blue. Then you'd ask what they thought of each episode. Did they give you real opinions or just say, "Oh, it was really good"?

They had opinions. I had been a teacher before I came out here, and the dynamics of teaching were very constructive for me in relation to the children. It was a blessing. Now they're adults.

What professions are they in?

Elizabeth and Olivia are writers, and my son, Benjamin, is an actor.

What do you do for fun nowadays?

The same things.

Like what?

I don't gamble the way I did. But I'm pretty much the same person.

Do you watch horseraces on TV or a computer?

No. But I do as a courtesy to a friend who owns horses, and that sort of thing. But I'm not a day-to-day participant in that activity.

So, do you have any hobbies or outside interests?

Well, none that I'll admit to.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #08, 2023 under the same title.