Excerpted from Call the Midwife: A Labour of Love: Ten Years of Life, Love, and Laughter by Stephen McGann

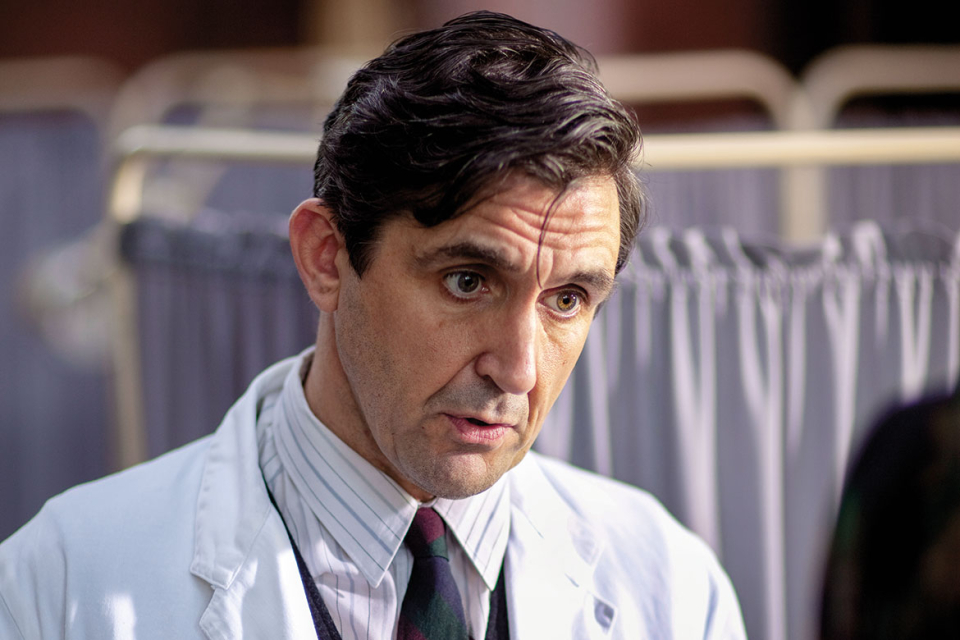

STEPHEN McGANN

ACTOR, DR. PATRICK TURNER

"Call the Midwife? That's just about babies being born, isn't it?"

I still get that sometimes from members of the public who've never watched the program. In truth, there is no "just" about it. When we first gathered to make season one in early 2011, a major task for the production team was how to create the joy, pain and breath-held drama of childbirth — in a way that fully respected medical practice and female biology — yet was watchable for a family audience. Until then, childbirth on screen tended to be a technical afterthought: a few seconds of light panting in full makeup before a three-month-old baby pops out.

This careless dismissal of such a profound process would regularly drive real midwives crazy. But not this time. We were going into that closed world of the birthing room and wanted to do justice to an event that every human being has experienced. As Dr. Turner, I was fortunate to play a small part in those early scenes — and so witnessed firsthand the incredible teamwork and expertise that achieved them.

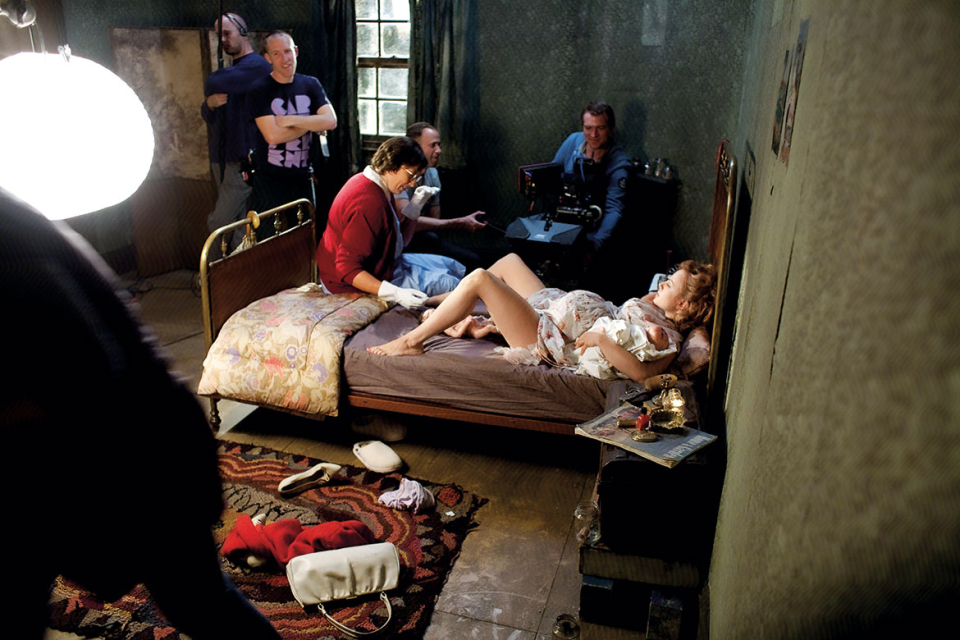

The birth in episode one was a hell of a way to start. As written by Heidi Thomas, the mother (played brilliantly by Carolina Valdés) had already given birth to twenty-four children! Conchita Warren spoke only Spanish and now was facing a premature delivery with life-threatening complications. Meanwhile, the young woman at the center of our story, Jenny Lee (played by Jessica Raine), was facing her first major challenge as a midwife. Those scenes would probably define the success or failure of our entire series. No pressure, then!

We were lucky to possess a secret weapon, our midwifery advisor and real-life midwife, Terri Coates. Terri had years of clinical experience and was determined to see her profession represented with dignity and accuracy.

Thankfully, we were also blessed with Philippa Lowthorpe as our director. Philippa immediately saw the value of close collaboration to create authentic births. Her key decision in season one was to set aside dedicated rehearsal time for a birth scene. Generally, TV actors turn up on the day of a shoot and rehearse immediately beforehand. Not here. Call the Midwife was going to spend the time to get Conchita's birth right.

We rented a room in the Bloomsbury Central Baptist Church in London. It had a few props — a makeshift bed, a child's doll for a baby — but all the important elements were there: Terri, Philippa and the actors Jessica, Carolina and Tim Faraday (who played Conchita's British husband, Len). I sneaked a few photographs on my mobile phone and watched as they worked together to solve the problems they encountered — Philippa listening to Terri's advice, encouraging the actors, and devising the right camera angles for the moments of dramatic focus.

Filming a birth without exposing too much is no simple matter. The event takes place, of course, at what a midwife might euphemistically call the "business end" of a woman's body — not exactly your normal Sunday-evening family location. But constraints can lead to real creativity. Philippa worked miracles in that room — devising how an arriving baby might be filmed using the angles, cutaways and reaction shots that would help viewers fill in the gaps with their own imagination.

Jessica had such a difficult journey to make as Jenny in that first birth. Assisting at a dangerous labor that would change her life, Jenny was feeling every fear and emotion while needing to stay composed. Jess would guide viewers through those key moments, and what she achieved was a benchmark for all Call the Midwife performances to come.

Terri, of course, knew better than anyone the extraordinary sounds a woman can make during labor — guttural, animal, primal and as far removed from Hollywood panting as you can imagine. During rehearsal she performed them for us, and we listened, open-mouthed. How could we possibly present that to a Sunday audience? Yet Carolina took those sounds inside of her and made them Conchita's. Her performance was extraordinary.

In the final run-through, Carolina let it rip with all she had: raw emotion, pain, love and passion. At the end of the scene there was a stunned silence. Nobody moved. I looked across the room and, to my surprise, I saw Terri — who'd delivered hundreds of infants — wiping tears from her face. She'd told me that birth usually made her cry. But this was just drama, make-believe. Why had she responded in that way now? "Because it looked right," she sniffed. "It felt real."

That was the moment I first suspected that Call the Midwife was a lot more than "just" about babies being born. But let's take a step back to the beginning....

PIPPA HARRIS

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

Jennifer Worth (born Jennifer Lee) had written three books about her time as a midwife in the East End of London in the 1950s. The first, Call the Midwife, was published in 2002 as a small run of copies by a tiny publishing house, Merton Books. Jennifer's agent thought it might have wider appeal, and it was sent to us at Neal Street Productions as something that might make a good film.

Our head of development at the time, Tara Cook, took it home to read and couldn't put it down. She passed it on to me and I found it fascinating — there was something that felt so immediate, but at the same time it was almost like reading Dickens or a historical novel. The level of poverty depicted was so extreme and so different from today, and yet it was only fifty years ago.

Jennifer had a real knack for episodic storytelling and was very good at vignettes. She was a natural observer, giving vivid descriptions of the people and medical situations she encountered in the East London community of Poplar. You didn't always get a huge insight into her as a person, but you got a good sense of her as an intelligent, poised young woman looking at an unfamiliar world and trying to make sense of it. She was at the center of an ensemble of fascinating characters, and I thought that would make the book ideal for television.

It can take a long time to find the right person to adapt a book for television. We often have to go to many people, and it can take months. In this instance, I had a gut instinct that Heidi Thomas would be perfect. We did our first jobs in television together, on the series Soldier Soldier — which was where we both met Annie Tricklebank, who has gone on to produce so many seasons of Call the Midwife. I knew that we needed someone who would understand the complexities of people's lives in Poplar and would depict that world in an empathetic way.

Heidi is extremely technically skillful, and there was good, raw material in the books. But it wouldn't be like adapting a classic — there wasn't really a story. We needed someone who could structure that story and create a series that could run and run. I loved the way Heidi had adapted Madame Bovary and Cranford for television, but I wasn't sure that she would be so keen on adapting the work of a living author. There's a freedom that comes with the author not being around.

HEIDI THOMAS

CREATOR–WRITER–EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

When Pippa sent me Jennifer Worth's book, I took one look at the cover and thought, "That's not for me." It had a photograph of some very scruffy urchins, which put it into a category that was known at the time as the "misery memoir." I'd just done Cranford, and I was definitely thinking about nineteenth-century fiction rather than twentieth-century nonfiction. So it sat on my desk for six weeks, until Pippa rang me up and said, "Please, just read twenty pages."

So I did — and I got as far as page seventeen, where there was a description of a working-class East End woman giving birth and the narrator thought to herself, "How much can she bear? How much can any woman bear?" In the middle of a very detailed description of a particular physical event, something completely universal was expressed. At that point I didn't even bother carrying on — I just emailed Pippa and said, "Yes."

PIPPA HARRIS

Once Heidi was on board, we had a project. We knew that medical stories work really well on television, and with the combination of nurses and nuns [the nurse-midwives of Worth's books were attached to a convent], we had plenty of interesting characters. It was also important for Jennifer to be happy with our choice of writer and to know that Heidi would stick to the spirit of her books. But if the show was a success, we would need to run beyond those books, as we would run out of stories.

Luckily, Heidi and Jennifer got on very well. I'd been looking for a new Cranford and, surprisingly, this was it. Cranford was a fictionalized memoir, and the first volume of Jennifer's memoir was more fictionalized than is generally realized. I quickly recognized that what lay before me was something very rich with potential, but it was complex — you could read three chapters and realize that it would make about ten minutes of television. Or you could read a paragraph that had such a complicated texture that it could make almost an entire episode.

HEIDI THOMAS

My first meeting with Jennifer — along with her husband, Philip, and with Pippa — was not a great success. We met at a rather posh restaurant in London where the acoustics were so bad that none of us could really hear what anyone was saying. Fortunately, it was followed up quickly by an invitation to lunch at the Worths' house in Hemel Hempstead, in north London.

It was a very snowy day and the roads were icy, but they had a fire going in the living room, dominated by an enormous Steinway grand piano that Jennifer played to concert standard. We talked, and a friendship started to develop. When it came time to leave, Jennifer helped me on with my coat, which was navy blue with a very full skirt. She took a great interest in clothes, and as she buttoned me into that coat, she remarked appreciatively on the lining. It felt like part of the audition process and that I'd passed.

What followed was a wonderful period of work with Jennifer. I'd go to her house, and we'd sit in what she called the Blue Room, not so much going through the book as having it there, as a shared property. She'd think back on her experiences and jot down notes in her spidery writing — you can see that in the opening credits of the show. They weren't fully formed sentences, just bits and pieces she remembered, like "Street games, skipping, children in go-carts made of crates with old pram wheels attached" or "Laundry hanging everywhere."

Those notes turned out to be the gift that kept on giving. I'd go back to them and find "Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts, youth clubs" — and they became essential elements of the society we ended up showing on screen. After she read my first draft, Jennifer only had one specific comment, and that was about the cake that had to be hidden from Sister Monica Joan (Judy Parfitt) to prevent her from eating it all — it was hidden in a stewpot, not a cake tin!

Jennifer was a quick study and comprehended the process very rapidly. I'd never worked with a living writer before, and I had huge respect for her and for her work. She knew that, and it was a great moment when she said, "I'm going to leave this to you now. You do what you think is right and I am sure it will be correct."

It was a two-way street, and she was happy to have her brain picked. And she was very interested in how we were going to recreate the East End that she remembered. As a young midwife, she'd cycle up to twenty miles a day across the Isle of Dogs, over river bridges that are no longer there. Probably 80 percent of the environment she remembered no longer exists. We had to explain computer-generated imagery to her, and she was fascinated by that.

HUGH WARREN

PRODUCER, SEASONS 1–3

Finding our convent, Nonnatus House, was key to the first season. We were incredibly lucky to find a house in north London — it was an old seminary with lots of buildings that we could use. There's a great benefit when you're filming of being able to do a lot in one place. Because so many people are involved — in front of and behind the camera — it really helps if you're not moving the crew around all the time.

There was a big chapel for the nuns, a kitchen and various other areas that worked really well. We knew that the site was owned by a developer, but we thought it was worth the risk, that we'd have a bit longer there than what turned out to be the case. After the second year, the owners wanted to start work on the development, so we had to move on. That was a real challenge, losing that physical world after we'd worked so hard to establish it.

HEIDI THOMAS

During preproduction in 2011, Hugh, Pippa and I made plans to go with Jennifer and her husband to see the original Nonnatus House, where Jennifer had worked. It was called St. Frideswide's Mission House and still stands as a big, red-brick 1890s building on Lodore Street in Poplar. We agreed to meet at Aldgate tube station, but the day before we got an email from Philip saying that Jennifer wasn't at all well. Within a week she had a diagnosis of terminal cancer. She lived only another ten weeks; it was desperately sad. We needed, wanted, her involvement in the show, but there was very little she was well enough to do.

Jennifer's books are a mixture of invention and reality — she didn't just write things down as journalistic facts; she was creative and imaginative and developed her characters, sometimes based on real people, sometimes not. Jennifer had told us that she loved the casting of Jessica Raine as Jenny Lee, her fictionalized self. They never met, but we showed her pictures of Jessica.

Dr. Turner was an invented character; Sister Monica Joan had elements of Monica Merlin, an actress who was Jennifer's lodger for a while. Sister Julienne (Jenny Agutter) was a real person, who remained friends with Jennifer for the rest of her life and wrote letters with little drawings in the margins to her two daughters. In fact, Jennifer remained in touch with the whole of that religious community, to whom she gave the fictional name of the Order of St. Raymond Nonnatus. She was a devout Anglican and used to stay with them and go on retreat.

I have an uncle who's a priest and whose ministry was in Birmingham, so when I was doing my initial research I told him that I was trying to identify an order of Anglican nuns who had roots in community nursing and midwifery in the East End of London. He said, "I know exactly who they are. They're the Order of St. John the Divine and they're now based in Birmingham." I asked Jennifer if that was correct, and it was. With her permission, we contacted them, asking if we could visit for purposes of research, and they were extraordinarily warm and welcoming.

JESSICA RAINE

ACTRESS, JENNY LEE, SEASONS 1–3

I'd begun my career in theater, and that grounding gave me confidence, but I was unsure of how to work with the camera. I remember thinking that I had bombed the first audition. Once I'd gotten the job, someone told me that I nearly didn't get a callback. Thankfully, Philippa, our director, saw something and the next audition was much better. I'll certainly never forget pretending to do a vaginal examination while sitting at a desk in the cold light of day! It was surreal and very funny.

I was already familiar with Jennifer Worth's original book, so I felt I had a good foundation in the world it was portraying. Heidi's script illuminated Jenny's naïveté going into the poverty-stricken East End. We are introduced to that world and to Nonnatus House through her eyes, so I knew it was a special part that needed some grit and humor alongside the innocence. Jenny needed to come across as young and inexperienced, so I upped the poshness of my accent and made my voice lighter than it is in real life.

The uniform helped establish the character as well. It was so comfortable, and I will forever be indebted to costume designer Amy Roberts for that — and for Jenny's off-duty wardrobe, in which there were lots of lemony-yellow colors and cinched-in "New Look" skirts and dresses. Jenny Lee always looked as if she left an aroma of fresh soap wherever she went.

It was the best experience to be in every scene, every day, leading a show and learning how to work with the camera. I loved mapping Jenny's journey and being guided by Philippa and working as a team.

PHILIPPA LOWTHORPE

DIRECTOR, SEASONS 1–2

I was quite surprised to be asked to direct Call the Midwife. Much of my previous work had been in documentaries with hard-hitting subjects, and I'd directed Five Daughters, a drama series about the women murdered by a serial killer in Ipswich in 2006. Pippa Harris came beetling up to me at an awards event and said, "I've got something for you." I thought, "Oh, good, I wonder what it could be." She sent me the books, and I was immediately caught and held. It was the most amazing opportunity to put women giving birth on primetime television.

Then I read Heidi's first script, almost without drawing breath, and I thought, "This is going to be a hit." She had written something that was rooted in the books that was authentic and real and, at the same time, a genuine drama. Heidi has this phenomenal ability to be funny one moment and heart-breaking the next, intimately moving and then powerfully angry. I couldn't believe my luck.

I was asked to go and talk about it, a sort of interview, with Pippa, Heidi and Hugh Warren. It turned out to be the easiest interview I've ever done — I can't remember what I said, if anything, but Heidi talked nonstop, Hugh smiled, Pippa smiled and that was that.

Hugh put together the amazing design team of Eve Stewart on production and Amy Roberts on costumes. I was the lucky beneficiary, and it was an extraordinary privilege to be there at the very beginning. I learned a great deal from Eve about manipulating design and getting the right feel and atmosphere.

Like Eve, Amy and I are both inveterate researchers and we all have extensive collections of photography books. There were phenomenal street photographers in the 1950s and '60s — Roger Mayne, who photographed children on a single street in west London over a period of five years, and Shirley Baker, who captured the lives of people in working-class, grindingly poor areas of Manchester. Their work proved inspirational.

Thanks to Heidi, Amy and I also went to Birmingham to visit the nuns of St. John the Divine and got them to show us their wimples! We had lunch there, and our talk had a big influence on me. It helped me understand that part of the story — the nuns and the religious life, their devotion and the sincerity of their belief.

JESSICA RAINE

The birth scenes were exhausting — not least for the actress performing the labor! In preparation, I watched a lot of One Born Every Minute [the docuseries set in a labor ward]. But I also think that growing up on a farm — watching animals giving birth and my dad helping deliver them — prepared me for the pragmatic nature of portraying a midwife. There's no room for squeamishness, only the practical.

The first scene we shot was the Conchita Warren storyline, about a woman who'd had twenty-four children. I was boiling "urine" in a test tube, holding said test tube with a metal scissor contraption over a naked flame. It could not have been more "proppy," and there was absolutely no room for nerves or shaky hands.

Since it was the first labor and birth we filmed, we were all finding out what positions worked best for the most realistic portrayal. Later on, we discovered the use of kneepads — something I'm sure actual midwives would be grateful for! It was challenging and great fun. I particularly loved it when the real babies arrived. It massively focuses you when you are holding a perfect little baby.

Copyright 2022 Neal Street Productions Limited, available wherever books are sold. Excerpt edited and printed with permission.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #6, 2022, under the title, "Breathing Room."